On Wednesday Donald Trump’s White House announced a proposal for new legislation that would cut the number of legal immigrants to the United States in half and offer preferences to English-speaking immigrants. Given Trump’s xenophobic and anti-Hispanic campaign rhetoric on immigration, some wondered whether the new policies were crafted to limit the entry of certain ethnic groups. Trump’s new policy proposal harkens back to a darker time in the United States. Remembering one particularly underexamined episode from this period helps clarify just how frightening a direction such anti-immigrant policies can turn.

In the midst of one of this country’s worst anti-immigrant backlashes in the 1920s, a small portion of Washington state exploded. It was November 1927, and a mob was demanding the immediate deportation of foreign farmworkers. The immigrants were taking away jobs. Worse still, the imported workers were criminals, they said. And despite the efforts of local police, the workers were “bothering” white women on the streets.

Little is remembered today about the anti-immigrant “deportations” of Filipino workers from the fields of Washington’s Yakima Valley in 1927, but the story is more relevant than it has ever been. The men of the mob believed that since the Filipinos were brown-skinned and Asian, they should not be permitted to approach white women or compete with white men for jobs. The economic and sexual fears of the men were clear and openly expressed.

How did these 1927 deportations, now familiar to only a handful of researchers, end up erased from our history? Certainly the memory of these incidents is inconvenient and shameful, particularly the memory of the violence against the future comrades in arms of American soldiers at Corregidor and Bataan. Importantly, the racism underlying this shameful period of mass deportations is still with us—has never really left us.

The deportations began outside the farm town of Toppenish, when a mob of 30 white men stormed the house of Ellis Peregrino, a local Filipino man married to a white woman. The mob demanded that farmworkers staying at the couple’s home leave the valley by midnight. Other mobs raided Filipino boardinghouses the same night, smashing furniture and beating young men, with the goal of “deporting” all Filipino farmworkers from the valley.

The Filipinos were in fact United States “nationals” able to work legally throughout the country. But the white men saw them as “imported labor.” When Congress passed the Oriental Exclusion Act in 1924, residents of the Philippines were not included in the ban on Asian immigration. As a result, hundreds of young Filipino men were soon traveling to Eastern Washington to fill the increasing need for farm labor. And the men of the mob were not happy.

The following night, as clouds blanketed the valley and a light rain fell, 150 white men outside Toppenish piled into more than 30 automobiles and set off for town. They rounded up small groups of Filipinos and ordered them out of the valley under the threat of death. Some were forced onto trains. Others fled on foot, as mob leaders announced they were ready to “go to any length” to rid the valley of “Orientals.”

By the next afternoon, only a few farmworkers remained, at their peril. Sheriff’s deputies described the mobs as armed and determined to kill every Filipino they found. Those in Toppenish were told that if they were found in the valley after dark, they would be hung. Over a dozen Filipino workers were taken to the county jail for protection. This had all begun on a Tuesday, and by Saturday morning, order had finally been restored. Ultimately, hundreds of Filipino immigrants were reportedly expelled. And the incident, unfortunately, was followed by other mob deportations in the nearby Wenatchee Valley in 1928 and 1929.

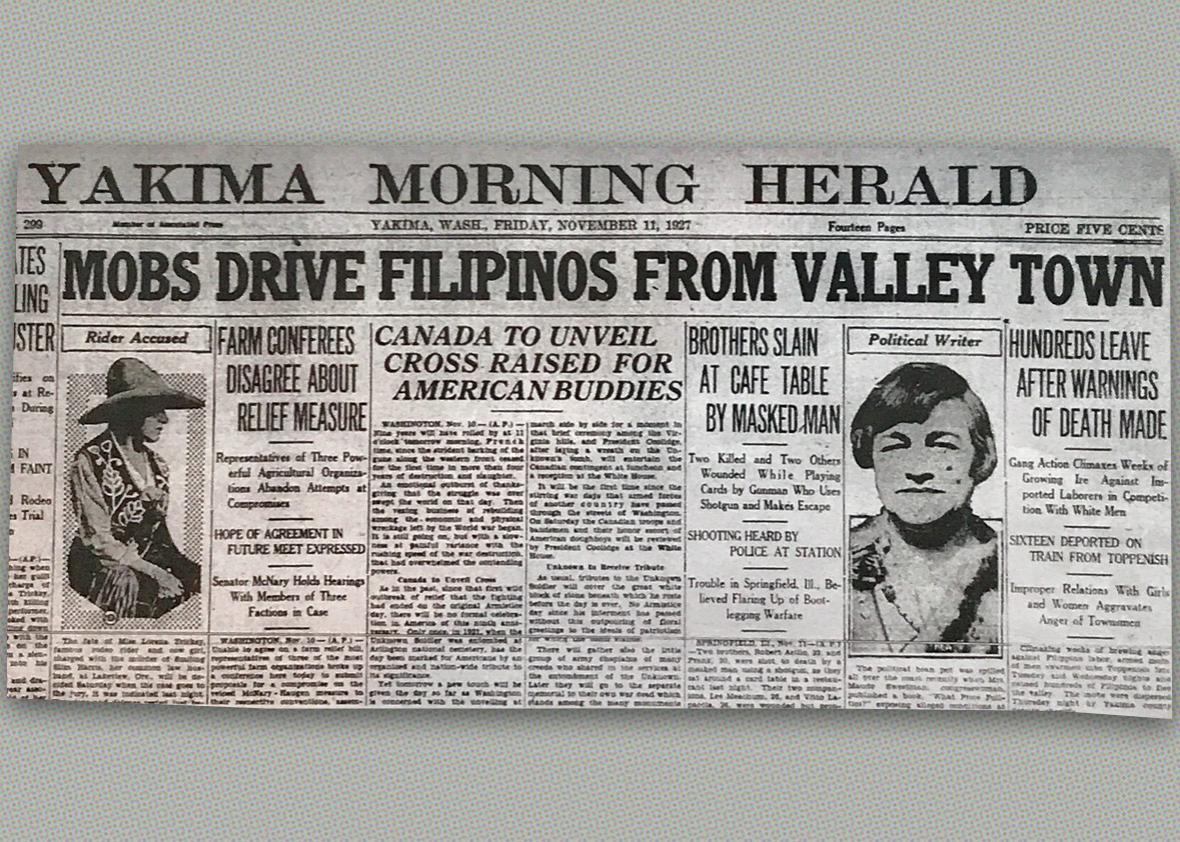

Newspaper reports of the time reflected racial sentiments that were largely accepted both in Yakima and Seattle. The Yakima Morning Herald’s headlines outlined what were seen as the underlying causes of the incidents: “Growing Ire Against Imported Laborers in Competition With White Men” and the workers’ “Improper Relations With Girls and Women.” (While the local newspaper all but endorsed the causes of the mob violence, at least there was no candidate for high office suggesting that the Filipinos were “rapists” or urging crowds of angry white men to “get them the hell out of here.”)

The Yakima Valley community’s response to the mobs might sound somewhat surprising in retrospect. The Toppenish Commercial Club immediately passed a resolution condemning the mob actions, and county authorities vowed to prosecute members of the mobs. Even in the midst of the virulent racism of the time, just three years after Ku Klux Klan “patriotic rallies” in Seattle and Yakima, the community did recognize the existence of certain 1920s societal norms. Leaders of the mobs were charged, and arrested, and put on trial. And mob leaders were convicted by a jury of white men.

Ultimately, the leaders were sentenced to only 10 days in jail, a slap on the wrist for the violent acts of a would-be lynch mob that expelled hundreds of people. But a little over a month after mobs had roamed the streets, remaining Filipino residents of the valley were able to gather for their annual Rizal Day celebration, and a prominent Republican legislator was the main speaker at the celebration. The response of the government leaders does not erase the racism, outrageousness, and lawlessness of the deportations, which were despicable in every way. But it is notable when compared with the rhetoric coming from today’s White House. Ninety years after the Yakima deportations, white nationalists have found a kindred spirit in the president of the United States who continues to keep the spirit of the mob alive and well.