This article is adapted from Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War.

On July 4, 1872, settlers of the Grande Ronde Valley in northeastern Oregon paraded through the streets of their tiny county seat, La Grande, before sitting down for a feast and public recitation of the Declaration of Independence. Afterward, two guests stayed behind—large men about 30 years old, their long braids banded and feathered, wearing bright blankets, clusters of necklaces, and intricately beaded shirts and leggings. In the 10 years of La Grande’s existence, local Indian chiefs had regularly attended Fourth of July celebrations, affirming peace and friendship with the United States. A settler introduced the guests as Joseph and his younger brother Ollokot, leaders of a nearby Nez Perce band. Joseph declared, as others had before, that he and his people had been “ever true to the whites.” But he had journeyed from the Wallowa Valley just over the mountains to the east with an additional agenda in mind.

Joseph and his brother had come to La Grande to speak with the area’s congressman, who was home for recess, and a local man who had just finished serving as the federal superintendent for Indian affairs for Oregon. That spring, when the families in Joseph’s band had begun moving their horse and cattle herds from the deep canyons of the Imnaha and Snake rivers up into the Wallowa Valley, they had found settlers on their ancestral land marking off homesteads and building rough shelters. Joseph sought them out and calmly informed them in Chinook Jargon, a widely spoken regional trade language, that they were trespassing. The settlers responded that an 1863 treaty had put the Wallowa Valley in the public domain. Homesteaders were registering their claims at a federal land office in La Grande. There would only be more of them.

Joseph told settlers that this was a matter for “the authorities at Washington.” He believed the government had made a mistake. In 1863, in the midst of a gold rush that was devastating Nez Perce country in Idaho Territory, leaders of several Idaho bands had signed a treaty that guaranteed them their own lands, which only constituted about 10 percent of Nez Perce territory. According to the treaty, everything else, including the Wallowa Valley, would be ceded to the United States. Joseph maintained that the Idaho bands had no authority to negotiate away his land. His band was autonomous and independent, lived 100 miles away from the bands that signed onto the treaty, and had not been represented at the council. The issue seemed straightforward to Joseph. He likened the notion that the Idaho treaty applied to his people to the government claiming it owned his horses after paying his neighbor for them.

But how could he persuade the government to change course? He was more than 2,500 miles from the capital, in a valley ringed by mountains so high that settlers had to take apart their wagons, haul them uphill, and reassemble them at the top. He did not speak English. As a Native American living a traditional life, he was not regarded as a citizen and could neither vote nor sue the government—rather, he represented a separate sovereignty. And in any event, Native American land claims had never found sympathetic ears in Washington. But Joseph was not easily deterred.

He began by seeking out every federal official he could find. Joseph argued that his people had never consented to and were not bound by the 1863 treaty. The congressman and former Indian superintendent at the Independence Day festivities in La Grande heard him out and then told him the same thing that he would hear again and again from people representing the government: that they respected his position, agreed with him even, but lacked the power to change a thing. They made vague references to “higher authorities”—the only people who could resolve the Wallowa question—but revealed little sense of who these authorities might be. The federal government stretched across thousands of miles, extending its administration into the farthest reaches of the continent. At the same time, it was invisible, opaque, and inscrutable. Joseph had no way of knowing whether his words could cross mountains, canyons, rivers, and plains and find an audience that would grant him relief. A reporter observing the July 4 meeting believed that Joseph’s efforts were in vain, writing that “it is in the nature of things that this beautiful Valley will be settled immediately.”

But just nine months later, in April 1873, the secretary of the interior gave Joseph’s band permission to use the Wallowa Valley “for such time as the weather is suitable, according to their previous custom,” and promising future action to reserve the valley “for the exclusive use of said Indians.” In May, the General Land Office stopped registering Wallowa homesteads, and Oregon’s Indian superintendent announced his office would be buying out settlers’ claims. In June, President Ulysses S. Grant signed an executive order designating about half the valley—912,000 acres—as a “reservation for the roaming Nez Perce Indians.” It was an impressive, if fleeting, victory and an early test of the message and methods that would make Joseph an extraordinary advocate for his people over the course of three decades—and inspiration to activists and dissenters ever since.

* * *

After such an inauspicious beginning, how did Joseph find quick and stunning success? He regarded each official he met to be a conduit to Washington. With every conversation, word of encouragement, or rebuff, Joseph was figuring out how low-level administrators could help his words swim upstream. Bureaucrats on the edge of the continent had little power to change anything, but they did have some leverage. Isolated and largely alone, they had tremendous discretion in everyday affairs, and officials in Washington had to rely on their observations and opinions as they set policy. When frontier officials wrote letters to the capital, they could tailor their messages to attract the attention of their superiors.

In early 1873, the Nez Perce Indian agent John Monteith found a powerful audience when he compared the Wallowa situation to a war the Army was fighting against the Modoc tribe 500 miles away along the Oregon-California border. Unless Joseph’s land claims were resolved, Monteith warned, a second front in the war could open, or worse yet, a broad regional conflict could ignite. Awarded his job because of his close ties to Presbyterian missionaries working among the Nez Perce, Monteith was not naturally sympathetic to Joseph’s position. At a basic level, he wanted every Nez Perce man, woman, and child to move to the reservation that he controlled, give up their lives as nomadic herders to farm small plots of land, and embrace Christianity. But the Wallowa Valley land claims presented Monteith with a rare opportunity to force the Indian Office to notice and engage with him—if he could frame the issue with enough urgency. The agent’s ambition and self-interest connected Joseph’s arguments with the authorities who mattered. Within weeks, Joseph had won back much of his valley.

When Joseph emerged as an advocate for his people, he was one of many Nez Perce leaders spread across the far-flung autonomous bands, outranked by older men who had long experience hunting buffalo and fighting rival tribes to the east—Blackfeet, Lakota, Crow. But Joseph made an outsize impression. People who negotiated with him described mesmerizing encounters. He didn’t just shake hands. He would clutch a hand and hold it, look down, and gaze deep into people’s eyes. It was a practice that suggested strength and confidence to his audience but also an irresistible vulnerability, revealing the purity of his motives. He could inspire trust and a flood of romantic descriptions, even from people who professed to doubt the very humanity of Native Americans.

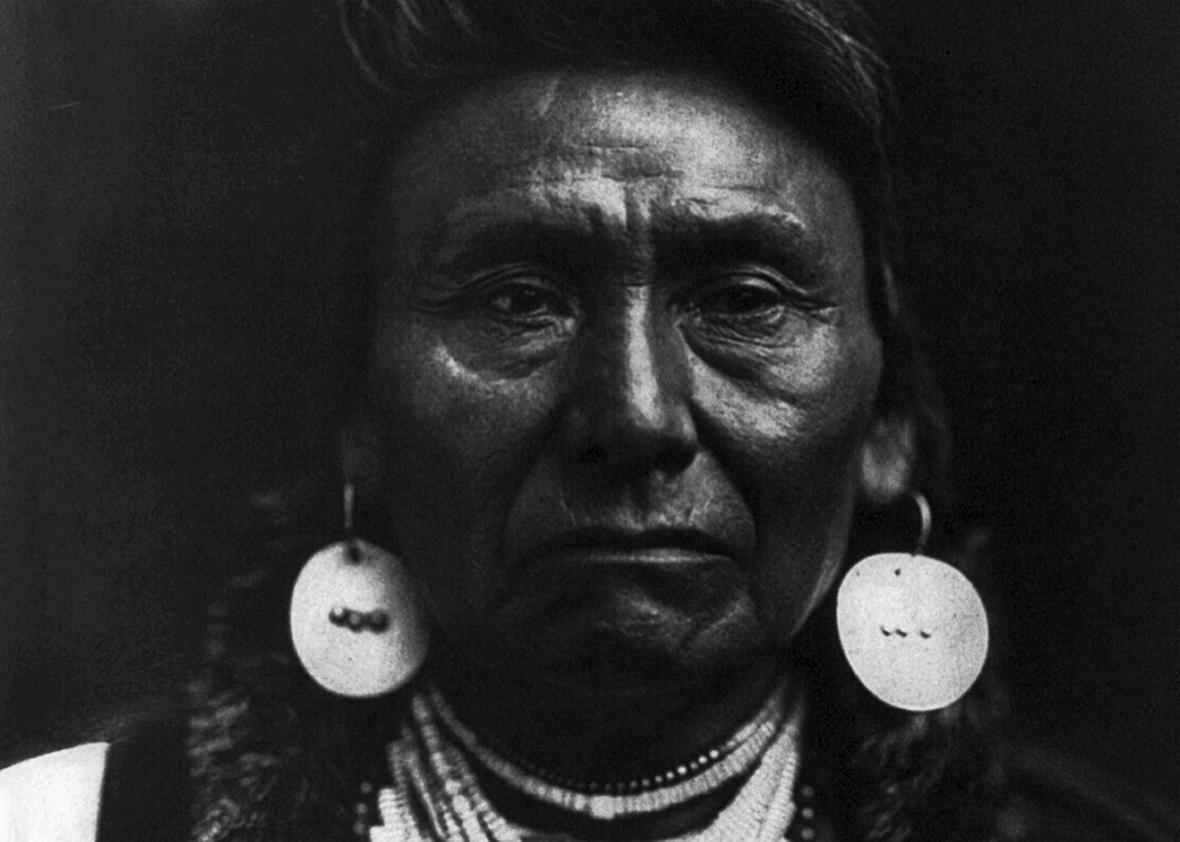

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter Photograph Collection/Washington State University

His charm held through the bitter disappointment of learning that Grant’s executive order did not resolve his people’s struggles. Oregon’s governor and congressional delegation protested, and the federal machinery almost immediately began to reverse itself. By spring 1874, the commissioner of Indian affairs was assuring Oregon officials that the Wallowa Valley would remain in the public domain and that “settlers … would not be molested in any way.” In the summer of 1875, President Grant signed a second executive order, giving the Valley back to white settlers.

Joseph was repeatedly told that he had lost, but he refused to regard the second executive order as resolving his claims with any finality. When a cavalry column was sent to investigate the situation in 1875, Joseph did not see the federal troops as a threat. Rather, he viewed the officers as additional bureaucrats to influence, with their own lines of communication to Washington. He convinced them that his people remained the rightful owners of the valley, prompting an official Army study that concluded, in January 1876, that Joseph’s people “cannot in law be regarded as bound by the treaty of 1863; and so far as it attempts to deprive them of a right to occupancy of any land its provisions are null and void.” At the same time, he impressed the officers with talk about co-existing with settlers in the valley, asserting his equality alongside his sovereignty. The Wallowa situation was effectively reopened.

Joseph intuitively understood how the American state worked. It had many faces and many competing authorities. Power in the U.S. was, and remains, split in countless ways. Among federal, state, and local governments. Among legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Between civilian and military authorities. And among agencies that overlap and compete with each other all the time. While the government after the Civil War was getting more adept at implementing policies—the technology of governing was improving—policymaking was wide open, responsive to outside voices and to the myriad people and institutions that could claim legal authority on any given issue. The distributed nature of American power almost begged its subjects to contest every decision. There was always someone else to turn to, and for Joseph, it seemed that persistence in this process could be leveraged into rights.

* * *

At the end of June 1876, Lakota warriors destroyed George Armstrong Custer’s army on the banks of the Little Bighorn, jolting the nation right as it was celebrating the centennial of independence. Weeks later, an Army general visited Washington from his posting in Portland, Oregon. Oliver Otis Howard had been a fixture in the capital during Reconstruction, leading the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, a new agency created to enable former slaves to claim their liberty and equality, and helping to found a new university for black men and women that bore his name. A lightning rod for Reconstruction’s opponents, Howard was almost driven into bankruptcy defending himself from corruption investigations, but after being cleared of all charges in 1874, he rejoined the active-duty military and was sent to command Army forces in the Northwest. For him, it was a willing exile, an opportunity to serve the nation outside the glare of partisan politics. It might also be a path to redemption, power, and prominence.

In meetings at the Department of the Interior, Howard presented the competing claims over the Wallowa Valley as the next great flashpoint between settlers and Indians, the place where another national trauma could occur, and he suggested that he be allowed to negotiate with Joseph. He was confident that by offering generous compensation for its land, he could induce the band to leave the valley for a reservation, just as he had done with the Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise in 1872. With Democratic and Republican newspapers hailing Howard’s ability to avert war, his redemption was at hand.

But when the general brought a commission to the Nez Perce reservation in November 1876 to settle the “Wallowa question” once and for all, Joseph refused any deal for his land. After years of seeing the Wallowa situation opened, closed, and reopened, Joseph did not take Howard at his word that the commission would have the final word on the matter.

Joseph framed his decision with ideas about liberty and equality, ideas that Howard had championed during Reconstruction. But the general responded angrily, warning Joseph that “he must not complain if evil happens to him.” Months later, in May 1877, Howard issued an ultimatum, giving all Nez Perce bands 30 days to move with their herds to the reservation, despite the fact that the many rivers that had to be crossed were at spring flood. Joseph thought he had no choice but to accept Howard’s terms. “I did not want bloodshed,” he would say. “I did not want my people killed. … I said in my heart that, rather than have war, I would give up my country. I would give up my father’s grave.”

Joseph’s band made the journey, surviving the torrential waters of the Snake and Salmon rivers. That June, on the eve of Howard’s deadline, as they and other bands gathered on the edge of the reservation, exhausted and despairing, a group of young warriors began targeting settlers along the Salmon River for a series of revenge killings. When the Army and local settlers came after the bands, Joseph’s vision of a negotiated solution vanished, a mirage in the canyons. Many warriors initially suspected that Joseph would cut some kind of deal and surrender. They followed other leaders now. Joseph stayed with his people and fought, but he would describe himself as “deeply grieved.” “I counseled peace from the beginning,” he would later say. “I knew that we were too weak to fight the United States. We had many grievances, but I knew war would bring more.”

For nearly a month, a few hundred Nez Perce families—about 750 men, women, and children, including maybe 250 men of fighting age—fought the Army and settlers in the canyons and prairies near the Idaho reservation. But in mid-July, after a grueling two-day battle in the bluffs above the Clearwater River, it became clear to the families that they were far outnumbered and had little hope of victory if they stayed in Nez Perce country. For the next 2½ months, they fled with more than 1,000 horses across the Bitterroot Mountains into Montana Territory, down through the Northern Rockies along the continental divide, through the newly created Yellowstone National Park, and finally straight north through the Montana plains toward the Canadian border, the “Medicine Line.” Along the way, soldiers surprised the families several times, massacred dozens, and repeatedly tried to trap and corner them. But each time, the warriors outfought them, and the families and their horse herd proved far more nimble on rough terrain. As they tried to justify their difficulty in catching the renegade bands, officers attributed all of their foes’ battlefield success to the leader they knew best. Even though Joseph was not a war chief, in the minds of his enemies, he was Achilles, Odysseus, Hannibal, and Napoleon.

In early October, besieged by soldiers just 40 miles shy of the border, the Nez Perce families fought to a stalemate. Most of the war chiefs were killed, leaving Joseph to negotiate surrender terms that would ensure the care of dozens of freezing and starving women, children, and elderly people. When newspapers printed what was said to be his surrender statement—in which he declared, “from where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever”—Joseph was immediately hailed as a “great chief.”

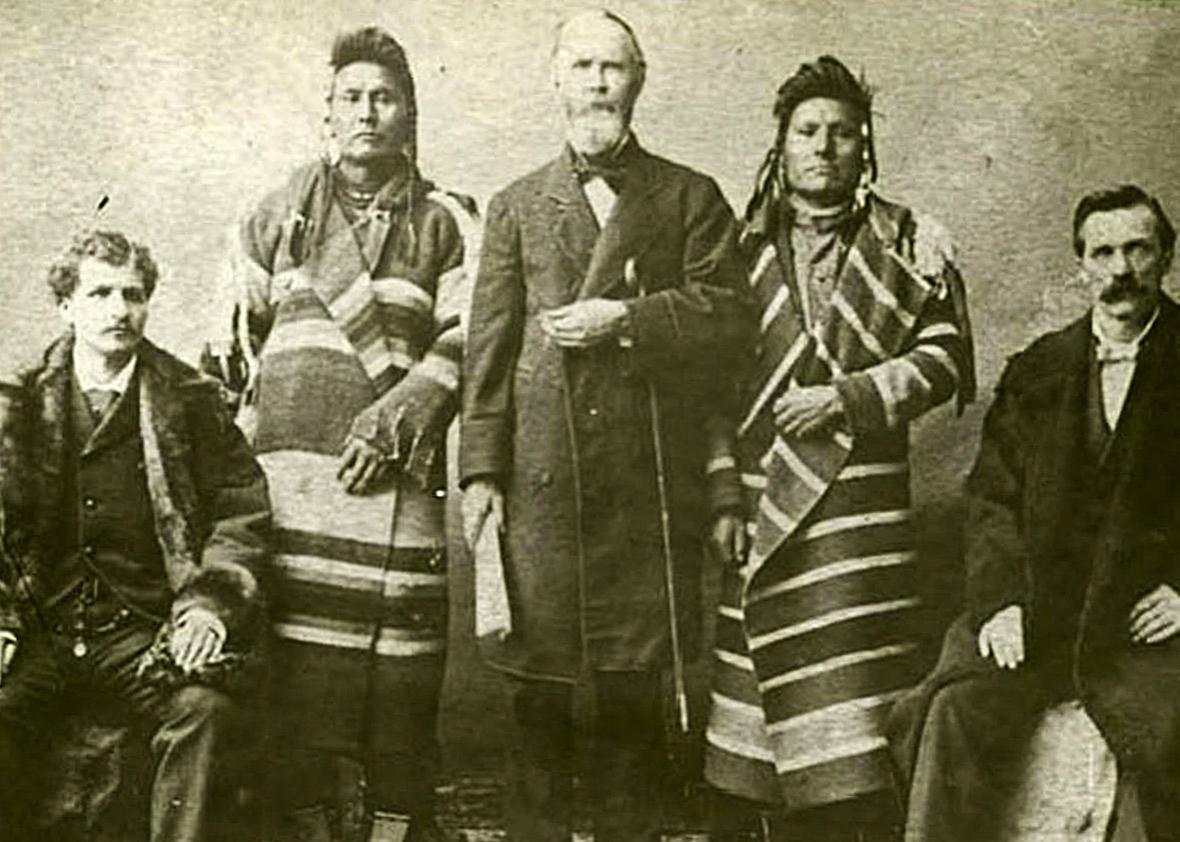

Library of Congress

Imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth for the winter of 1877–78 and then exiled to Indian Territory, hundreds of Nez Perce War survivors died from malaria, cholera, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and suicide. At the same time, Joseph achieved national renown. Once he had made peace with such eloquence and exquisite sentiment, he was easy to celebrate as “a most interesting blending of the old and the new,” as the anthropologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher wrote upon meeting him. “One could not help respecting the man who … stood firmly for his rights,” her companion Jane Gay added. Thousands of people tried to visit him in exile, and when he was invited to speak in the capital in early 1879, he found himself the sensation of Washington society. Commanding General of the Army William Tecumseh Sherman, who during the Nez Perce War had envisioned Joseph dangling from a rope, cut through the crowd at a White House ball, shook the chief’s hand, and introduced him to his daughters. Nelson Miles, who had led the forces that finally caught the Nez Perce families, declared the chief “the best Indian” he’d ever met. Joseph’s surrender speech was widely recited in schools.

As Joseph’s celebrity grew, as he paraded at the dedication of Grant’s Tomb and received an ovation as an honored guest at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, journalists and early historians had difficulty separating the man from the myth. But Joseph remained remarkably constant in his advocacy. While Oliver Otis Howard urged Joseph to stop fighting and acknowledge that he would be in Indian Territory forever, Joseph pleaded to any official who would listen for his people to be restored to the Northwest, much as he had pleaded his case before the war. Enlisting allies in the Interior Department and the military, and inspiring sympathetic whites across the country to petition Congress, Joseph again found leverage, and in 1885, 118 survivors were allowed to settle on the Nez Perce Reservation, while Joseph and 149 others were taken to the Colville Indian Reservation in north-central Washington state.

Joseph never stopped pressing for land in the Wallowa Valley, and up to his death in 1904, the government kept reopening and reconsidering his claims. Joseph became an inspiration to generations of civil rights and human rights activists due his forceful message of universal liberty and equality. “We only ask an even chance to live as other men live,” he famously said. “Let me be a free man—free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.” It’s a strikingly modern expression of the rights that all Americans should expect, marking a bridge from the old values of abolition, the Union, and Reconstruction to the causes of a new century. But Joseph was not simply making a plea for citizenship. He was claiming the right to participate in the contentious, if not unending, struggles built into the American way of governing—the right to speak to the state and be heard.