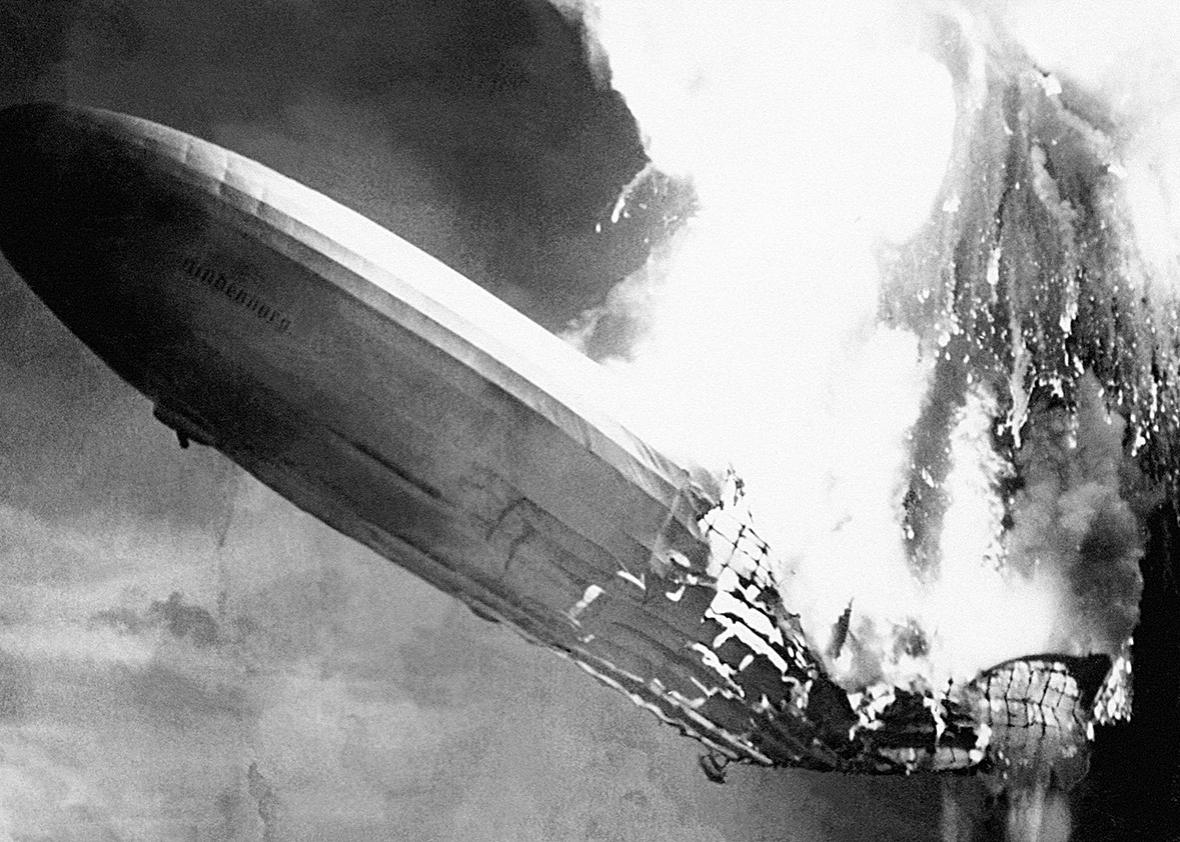

Eighty years ago this week, the airship Hindenburg erupted into flames while nearing the mooring mast at New Jersey’s Lakehurst Naval Air Station. From a nearby hangar, radio reporter Herbert Morrison described the unfolding horror. Thirty-six people died in the Hindenburg airship fire. Morrison, employed by Chicago radio station WLS, had traveled to Lakehurst equipped with a new type of portable recording device, and his emotional description of the conflagration became one of the 20th century’s most famous broadcasts.

Morrison’s recording offered the nation a first glimpse of broadcast journalism’s stunning emotional potential. “Oh, it burst into flames, get out of the way, please … this is terrible!” Morrison cried. “This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world!” A year later, actor Frank Readick listened to Morrison’s Hindenburg broadcast to prepare for his role as panic-stricken newscaster Carl Phillips in Orson Welles’ production of War of the Worlds. Readick’s mimicry of Morrison’s performance jolted listeners, just as Morrison’s emotional cry of “Oh, the humanity!” had resonated with those who heard his heart-rending words in real time.

Morrison’s recording structures popular memory of the Hindenburg. But that program’s historical legacy obscures another series of Hindenburg radio broadcasts that remain little-heard and largely forgotten. Those programs, airing on NBC in 1936, dazzled radio listeners in the United States. In broadcasts from Germany, and live relays transmitted from high above the Atlantic, Americans previewed futuristic transportation while peeking in on the lives of the rich and famous. Crossing the Atlantic by airship, in about 2½ days, seemed amazing. Doing so while enjoying sumptuous meals, relaxing in a reading parlor, enjoying cocktails at a bar, or listening to a pianist playing popular tunes, made the experience the apex of Depression-era luxury travel.

NBC’s radio programs celebrating the Hindenburg comprised part of the propaganda campaign undertaken by Germany’s Nazi Party in 1936. That spring, in defiance of the Versailles and Locarno treaties, German troops marched into the Rhineland. A plebiscite ratifying that annexation occurred soon afterwards, and the Nazis used the world’s newest and most sophisticated airship—LZ 129, the Hindenburg—to rally the “Ja” vote by soaring over every big German city. The electoral landslide that followed boosted Hitler’s domestic support.

Then, in early May, the Germans inaugurated the North Atlantic air travel season by staging an extravaganza to send the Hindenburg off to the United States. The Nazi swastika on the ship’s massive tail fins, and the Olympic rings logo along its side, signaled the vitality of Germany’s political revolution and the excitement surrounding that summer’s global athletic festival in Berlin. Throughout 1936, whether travelling above New York City, Frankfurt, or Rio de Janeiro on its South American run, the Hindenburg impressed all who witnessed it.

At 4:07 p.m. on May 6, 1936, NBC cut into its regularly scheduled programming to bring American listeners a special live broadcast of the airship’s departure. Eduard Roderich Dietze, an English-language announcer for Germany’s Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft, or RRG, radio network, described the scene for American listeners. Thousands of spectators milled about, cheering and waving goodbye to the giant ship while a marching band played spritely tunes.

In this exclusive clip from the NBC Collection at the Library of Congress, Dietze describes the scene minutes before the launch.

Credit: NBC Universal Archives

The crowd quieted noticeably when the band stuck up “Deutschland Über Alles” followed by “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” The zeppelin then ascended and floated into the dark night sky—it was past 9:30 p.m. in Germany—as Dietze closed the broadcast with a reminder to keep tuning in for live updates as the Hindenburg cruised toward North America.

The following evening Max Jordan, NBC’s Continental representative, spoke to American listeners from the cramped radio room perched above the zeppelin’s control cabin. He described that evening’s excellent dinner and the Beethoven sonata enjoyed by the passengers earlier in the afternoon and mentioned that the Hindenburg’s airspeed in perfect weather would ensure its early arrival. The next day, Jordan updated the nation as the Hindenburg headed down the Atlantic coast from Canada. That broadcast included piano music played by Dresden musician Franz Wagner on the ship’s specially constructed lightweight grand piano. Jordan explained how the ship’s remarkable stability allowed him to sleep peacefully through a brief but violent thunderstorm the previous night. Aside from his NBC updates, Jordan also participated in special RRG broadcasts, beamed back to Germany and hosted by Kurt von Boeckmann, the RRG’s director of international broadcasting. These NBC and RRG programs were the first live broadcasts from a passenger airship aloft over the ocean, a remarkable technological achievement celebrated widely in newspapers and magazines.

NBC Radio/Wikimedia Commons

The media couldn’t get enough Hindenburg news. In June, after shocking the sports world by knocking out Joe Louis, German boxer Max Schmeling sped home aboard the great airship. In October, as the North Atlantic season came to close, the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (German Zeppelin Transport Company) arranged a special promotional “Millionaires Tour” to thank Americans for their support. A group of wealthy and famous people—among them Nelson Rockefeller, World War I ace (and general manager of Eastern Airlines) Eddie Rickenbacker, the presidents of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company and the General Baking Company, and Germany’s ambassador to the United States—departed Lakehurst for a 10-hour, 680-mile swing over New York and New England. “It was the most imposing passenger list in the history of flying,” reported the New York Sun. NBC’s John B. Kennedy broadcast live from the airship. “We’ve got enough notables on board to make the Who’s Who say what’s what,” he joked. Kennedy described the resplendent colors of the fall foliage as viewed from the comfort of the Hindenburg’s luxurious passenger lounge.

Then, one year later, it was over. The Hindenburg exploded on its inaugural North Atlantic run of 1937. The recording of that tragedy, and the ensuing sensational media coverage, ended the brief heyday of zeppelin travel. The world’s earlier fascination with the Hindenburg largely disappeared, consumed by the same inferno that destroyed the airship.

The future could have been different, as those 1936 NBC broadcasts show. Today, those forgotten recordings reside at the Library of Congress, where the Radio Preservation Task Force (of which I am a member) is working to save historical audio. Visitors can don headphones in the Recorded Sound Research Center and listen to John B. Kennedy marvel at the beautiful fall landscape as he soars high above New England. Like Herbert Morrison’s famous lamentation, this Hindenburg recording also echoes across time, but as a window on a past that’s disappeared rather than a preview of broadcasting’s electrifying future.