The revised travel ban President Donald Trump issued Monday may have been watered down in places, but its core remains as hostile as ever to Muslim immigrants and refugees. Many of us think of America as a welcoming nation and of Trump’s attacks on outsiders as an aberration. Sen. Charles Schumer called the ban “mean-spirted and un-American.” The New York Times declared that the executive order will erode our country’s “proud tradition of welcoming people fleeing strife.”

But for all the times we’ve taken in the huddling masses, we’ve more often shut the door on them—from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the longstanding, discriminatory 1924 Immigration Act to the turning away of the St. Louis refugee ship.

Our rejection of refugees is an inextricable part of the American story, and Trump’s ban hews to that narrative more than we’d prefer to recall. Even during the Obama years, we let in only a tiny trickle of the more than 65 million refugees in the world now—admissions in 2016 were capped at 110,000. (Trump’s order slashes that number by more than half, down to 50,000.)

One such black spot on our history mirrors the present moment particularly closely. In the late 1930s, the United States had a chance to save 20,000 Jewish children fleeing Nazi persecution, by means of a program that would have mirrored the British Kindertransport. The rhetoric used by opponents of that program—which most likely doomed the vast majority of those young refugees to brutal fates in concentration camps—is eerily similar to language we’re hearing today.

The proposal was born in the aftermath of Kristnallnacht, the Nazi-directed pogroms of November 1938, when thousands of shops, homes, synagogues, and hospitals were destroyed and thousands of Jews arrested and sent to prison camps. The news shocked the world. But in the United States, with the country struggling to climb out of the Depression and unemployment still a potent issue, there was little political impetus to relax the restrictive quotas.

The British were quicker to respond. A week after the violence in Germany, a group of prominent British Jews, including Chaim Weizmann, later the first president of Israel, approached Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and floated the idea of temporarily admitting child refugees into the U.K., with the Jewish community fronting the cost. Within days, the British Cabinet approved the plan. On Dec. 1, 1938, less than three weeks after Kristallnacht, the first train departed Berlin with 200 children aboard whose orphanage had been set afire during the pogroms. Ten days later, another train left Vienna.

The British initiative, with its focus on children, inspired some to ask why America couldn’t do the same. “There are at least 60,000 Jewish or partly Jewish children in Germany in danger of starvation, forbidden an education, subjected to psychological if not actual physical terror,” the Nation reported on Dec. 10, 1938. Britain “expects to take care of some 15,000 [children]. Can we do less?”

Two months later, a legislative plan was hatched: Sen. Robert Wagner, Democrat of New York, and Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers, Republican of Massachusetts, jointly introduced a bill to admit 20,000 unaccompanied child refugees, 14 or younger, into the United States. The bill stipulated that the costs of caring for the children would be borne by the private sector and, crucially, that the refugees admitted would not count against the quotas limiting U.S. immigration.

A number of prominent Americans threw their weight behind the bill: bishops and actors, former President Herbert Hoover, and New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Even the first lady let her support be known. “It seems to me the humanitarian thing to do,” Eleanor Roosevelt said at a press conference when asked about the bill.

But the opposition struck back with calls to, yes, put America first.

“Protect the youth of America from this foreign invasion,” thundered John Trevor, the head of the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies, a restrictionist organization with a reach of about 2.5 million members. Trevor had built a career for himself by railing against rising immigration and its pernicious effect on America’s national character. He helped shape the 1924 Immigration Act, which established the restrictive quota system that was explicitly designed to curtail Italians and Jews, excluded the Japanese altogether, and stood as U.S. policy for 40 years.

It’s not hard to hear the echo of Trump, who cautioned of a “beachhead of terrorism” forming inside America during his recent address to Congress and who has also railed about a foreign invasion, calling Syrian refugees “the great Trojan horse of all time.”

On occasion the anti-Semitism was blatant and casually dispensed: “Twenty thousand charming children would all too soon grow into 20,000 ugly adults,” remarked Laura Delano Houghteling, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s cousin and the wife of Immigration Commissioner James Houghteling. But more often, then, as now, those in opposition argued that the arrival of refugees would deprive the American-born and spoke more euphemistically about “internationalism” and “opening the gates.”

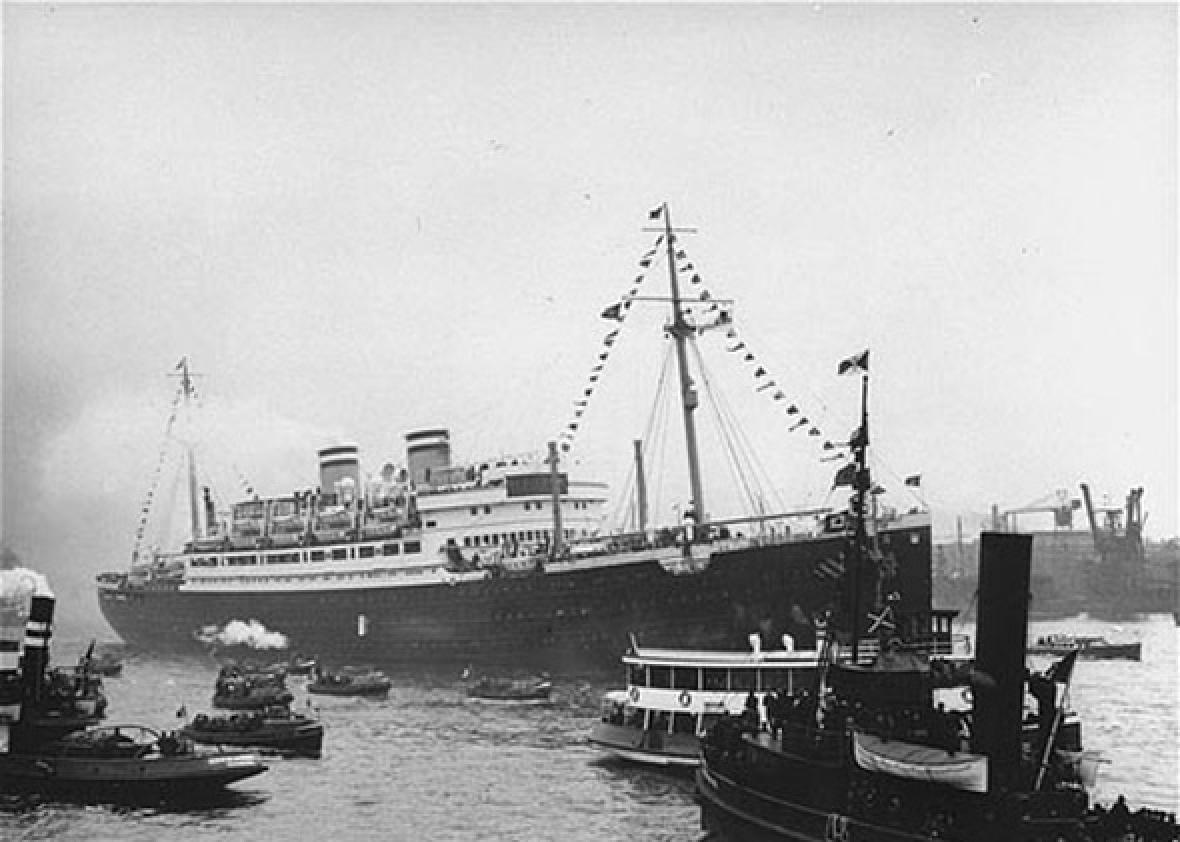

In April 1939, while congressional hearings on the refugee bill were being held, Fortune conducted a poll: If you were a member of Congress, would you vote to increase the number of European refugees currently admitted? Eighty-three percent of respondents said no. A month later, the St. Louis idled up the Florida coast with 900 refugees, only to be turned away. The prospect of inviting 20,000 children into the U.S. “is being opposed with as fiercely narrow a sincerity as if they were an invading host,” reported the New York Herald Tribune.

From the White House, there was only silence. Despite her initial approval, Eleanor Roosevelt never publicly announced her support, and neither did her husband.

By summer, the bill had been so drastically amended that the child refugees would now be counted against the immigration quota from Germany, bumping adults off the list. Sen. Wagner called this revision “wholly unacceptable” and said he preferred “to have no bill at all.” He soon got his wish.

During the months that the American bill was debated and denuded, the British Kindertransports continued. From December 1938 until September 1939, about 10,000 young refugees escaped Nazi Germany. The majority never saw their parents again. Many went on to become highly accomplished adults, including the film director Karel Reisz, the geneticist Renata Laxova, the writer Lore Segal, the Nobel Prize–winning chemist Walter Kohn, and the politician Lord Alfred Dubs.

Who knows what 20,000 children eligible for entry under the 1939 refugee bill could have accomplished. Or, more pressingly, what would become of a similar number of young Syrian or Sudanese refugees, if we only let them in.