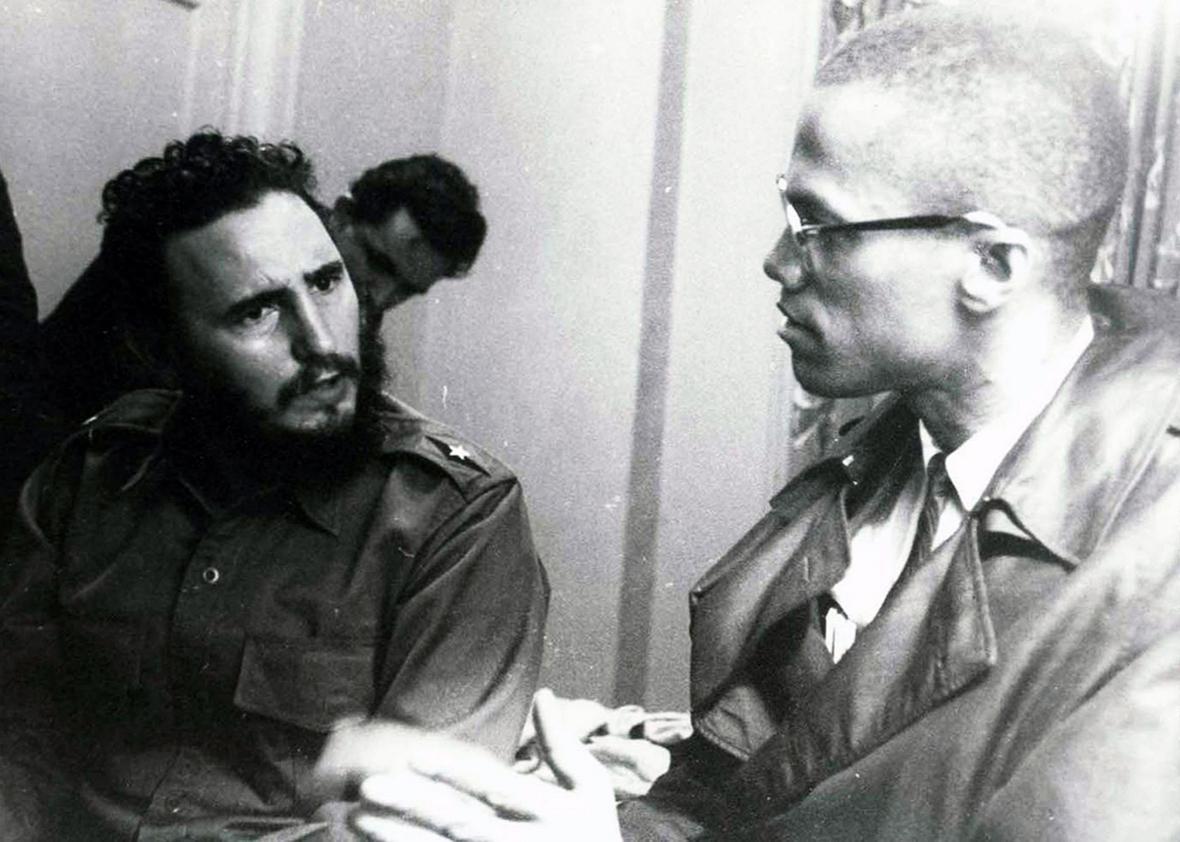

San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who has recently decided not to stand during the national anthem, wore a Malcolm X hat and a T-shirt featuring images of the leader meeting with Fidel Castro at a press conference where he explained his protest. The T-shirt has, perhaps predictably, drawn criticism from conservative quarters; the Weekly Standard called Kaepernick’s wardrobe choice a “startling display of ignorance,” pointing to what writer Mark Hemingway called Cuba’s human rights abuses and “legacy of racism.” Setting aside an assessment of Castro’s later record on race, and whether it strengthens or undermines Kaepernick’s stance, what’s the story behind those photos, taken a year after the Cuban leader came to power, and five years before Malcolm’s death? Why did the two men meet, and what did they discuss?

The photos, taken by Carl Nesfield, record a September 1960 meeting that was rich in symbolic significance. The Castro meeting illustrates Malcolm X’s internationalism—an important aspect of his activism in the last half-decade of his life that, scholars argue, has been unfairly cropped out of popular representations of his biography. While the meeting itself—which took place at the Theresa Hotel in Harlem during Castro’s longer visit to the city—was reportedly light on substance, its public relations value was immense. Harlem heartily welcomed Castro, demonstrating that the official American rejection of the Cuban regime did not represent unanimous public opinion, and that many Americans of African descent had come to believe they shared a common cause with others who had been oppressed abroad, including Afro-Cubans. And Malcolm’s prominent presence on the welcoming committee declared the rising leader—then a popular minister with an increasingly high profile within the Nation of Islam—to be a person of national and international importance.

Castro took power in Cuba in 1959. After initially recognizing the new government, the United States imposed a trade embargo the following year, reacting to Castro’s nationalization of industry and imposition of heavy taxes on American imports. When Castro came to New York in September 1960, for the 15th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, the incipient chilliness of the U.S.–Cuba relationship affected the conditions of his visit. He and his delegation were restricted to the island of Manhattan. After initially taking up residence in the Shelburne Hotel, in Midtown, the Cuban delegation found itself temporarily homeless when the manager apparently asked the Cubans to deposit a $20,000 security fee in cash, in order to continue their stay. Insulted, the Cubans looked around for other lodgings, at one point threatening to pitch tents on the grounds of the UN.

How did Castro end up in Harlem? In her 1993 book of interviews of people involved in the Malcolm-Castro meeting, journalist Rosemari Mealy speaks with Raul Roa Kouri, who was instrumental in orchestrating the move. Roa, in 1960 a relatively junior member of the diplomatic corps, remembers that the move to the Hotel Theresa—which opened in 1913, and was, by the 1940s, an integrated, black-owned establishment—was Malcolm X’s idea, relayed to the Cuban delegation via the activist group Fair Play for Cuba Committee. When Roa broached the idea of moving north to Harlem with Castro, Castro leapt at the concept, seeing a chance to bolster his argument that black Americans should support the new Cuba, where, he promised, Afro-Cubans would be lifted out of their historical oppression.

The reaction in Harlem was ecstatic. Writer Sarah Elizabeth Wright wrote in a remembrance included in Mealy’s book that she was at a meeting of the Harlem Writers Guild Workshop when the group got a phone call telling them Castro and the Cubans would be coming to the Theresa. “Unprecedented! No foreign government leader had ever considered lodging in Harlem to be sufficiently dignified,” Wright said. “Immediately, we scrambled for our coats and headed uptown to cheer Fidel, to make sure no harm befell him.” Crowds of Harlemites had the same idea. “Thousands of people were in the streets in front of the Hotel Theresa cheering the Cuban delegation,” activist Bill Epton told Mealy. “Every time a member of the Cuban delegation came to the hotel window, the masses of people would send up a mighty cheer.”

Some black community leaders protested the Cuban leader’s visit. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. told the New York Times: “We Negro people have enough problems of our own without the additional burden of Dr. Castro’s confusion.” But on the whole, Harlem appears to have welcomed Castro with raucous appreciation. Malcolm wrote in his autobiography that Castro “achieved a psychological coup over the U.S. State Department when it confined him to Manhattan, never dreaming that he’d stay uptown in Harlem and make such an impression among the Negroes.”

The meeting with Malcolm X happened at midnight on Sept. 19, just as Castro and the Cubans moved into their new quarters. Two reporters from black newspapers—Jimmy Booker of the Amsterdam News and Ralph D. Matthews of the New York Citizen-Call—were allowed to attend the meeting, along with freelance photographer Carl Nesfield, who had worked with Malcolm X on previous occasions. Booker told Mealy the meeting “was not a heavy conversation, lasting approximately 15 minutes, and between the interpreter and comments from one to the other along with comments made by other persons, it wasn’t really a hard news story. It was an exchange of pleasantries—a greeting in terms of the struggle, briefly expressing what it meant to each one of them. For me, there was no hard meat, in terms of substance for a story.”

Matthews’ story for the Citizen-Call recounts a meeting that was impeded by the language barrier and mainly focused on the exchange of expressions of solidarity. The two men sat on the edge of the hotel room bed during their conversation.

Castro’s first words were lost to us assembled around him. But Malcolm heard him and answered, “Downtown for you, it was ice, uptown it is warm.”

The Premier smiled appreciatively. “Aahh yes, we feel very warm here.”

Then the Muslim leader, ever a militant, said, “I think you will find the people in Harlem are not so addicted to the propaganda they put out downtown.”

In halting English, Dr. Castro said, “I admire this. I have seen how it is possible for propaganda to make changes in people. Your people live here and are faced with this propaganda all the time and yet, they understand. This is very interesting.”

“There are 20 million of us,” said Malcolm X, “and we always understand.”

During the remainder of the meeting, according to Matthews’ story, the two leaders covered topics including racial discrimination in the United States, U.S.–Cuba relations, and Castro’s plans for his speech to the U.N. General Assembly. (A transcript of Matthews’ piece can be found here, halfway down the page.) Malcolm’s biographer Manning Marable writes that Malcolm’s assistant Benjamin 2X “later claimed that Malcolm attempted to ‘fish’ Castro, inviting him to join the Nation of Islam.” This interchange didn’t appear in Matthews’ piece.

The Malcolm X–Castro meeting kicked off a series of meetings Castro held at the Theresa. While staying in Harlem, Castro also received visits from Nikita Khruschev, President Gamal Abdel Nassar of the United Arab Republic, and India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. After Castro was not invited to a luncheon given by Dwight D. Eisenhower for other Latin American leaders, he put together some counterprogramming: a lunch for the Hotel Theresa’s working-class black employees. The luncheon made for some great photo opportunities, giving Castro a chance to re-emphasize his preference for Harlem and its inhabitants over the fancier parts of Manhattan.

Malcolm and Castro never met again. Malcolm was supposed to meet with Che Guevara in December 1964, when Guevara was in New York to address the UN, but, “due to threats from right-wing Cuban groups in the United States,” Mealy writes, “Guevara was forced to cancel a visit to Harlem.” Meanwhile, although Malcolm became increasingly focused on international activism in the last years of his life—writing about the black struggle and anti-colonialism as a shared intercontinental project and making well-received visits to Africa and the Middle East—he never went to Cuba. (Marable writes that “Malcolm surely sensed that any official relationship, while useful, would create great difficulties for him with the authorities. One report suggests that, after the [Harlem] meeting, Malcolm was repeatedly invited to visit Cuba, but made no commitments.”) Malcolm was assassinated in 1965. The Hotel Theresa closed in 1966, and the structure was converted into an office building, the Theresa Towers.

The photographer Carl Nesfield, who tried and failed to sell the images of Fidel and Malcolm to “a lot of white newspapers” right after the meeting, told Mealy in 1993 that he had no idea his photos would end up possessing such historical cachet. “It’s only been recently that I was made aware of how the picture that I took has been used over the years,” Nesfield said. “I recently tried to get the picture copyrighted, but the copyright lawyers said ‘After all of these years, you might as well forget it.’ ”