This article is adapted from Whistlestop: My Favorite Stories From Presidential Campaign History.

“A Scotchman of Whom Nothing Good Is Known”

The presidential campaign of 2016 was destined to be the Hamilton election. Political campaigns can’t resist popular culture tie-ins. Hillary Clinton did her part in her acceptance speech. “We may not live to see the glory,” she said, quoting from the song “The Story of Tonight,” but “let us gladly join the fight.” Hamilton chronicles the bitter election of 1800, which is a favorite for anyone trying to put the nastiness of a contemporary campaign in context. “This election is no more bizarre than the one in 1800,” Hamilton’s creator Lin-Manuel Miranda told Rolling Stone. “Jefferson accused Adams of being a hermaphrodite.”

Jefferson didn’t actually use those words, though he paid for them, a small distinction that points out a large shift in our current campaign. The man who called Adams “a hermaphrodidical character,” James Thomson Callender, was working for Jefferson as a political attack dog. Candidates don’t need attack dogs these days; they do the attacking themselves. Clinton and Trump mentioned each other nearly 40 times in their convention speeches. Last campaign, Obama and Romney mentioned each other only 13 times. The Washington Post points out that in 2004 there were only three such mentions.

James Callender has been mostly forgotten—no one plays him at the Richard Rogers Theatre—but he was a key character in the Hamilton-Jefferson feud. He ruined Hamilton’s chances at the presidency and committed the end of his life to derailing Jefferson. A scandalmonger, drunkard, and host body to lice, Callender exposed both Jefferson’s and Hamilton’s private affairs, two of the greatest sex scandals in the early republic. “He was a Scotchman of whom nothing good is known,” wrote John D. Lawson in American State Trials, a 1918 account of Callender’s celebrated prosecution under the Sedition Act in 1800. “He had the pen of a ready writer and the brazen forehead of a knave.” Jefferson and Hamilton didn’t agree on much, but they both hated James Thompson Callender.

When Callender came to America from England, he was already on the run. He had attacked Samuel Johnson and the King of England, once referring to his government as a “mass of legislative putrefaction.” Facing sedition charges he fled, landing in America on May 21, 1793. He believed that here he would have a chance to unbuckle his talents. “It was the happy privilege of an American that he may prattle and print in what way he pleases,” Callender wrote, “and without anyone to make him afraid.” His career would test that proposition. Callender secured one of the four official stenographer posts in the new Congress when it moved to Philadelphia not long after he arrived in America. Newspapers paid stenographers, not the government, which meant scribes were constantly accused of embroidery, making their foes sound dumb and their allies brilliant.

The newspaper wars of the 1790s, in which Callender enlisted, were ferocious. “The golden age of America’s founding was also the gutter age of American reporting,” writes historian Eric Burns. Papers were partisan, not impartial. Editors attacked each other in the street, cursing each other with prolixity and backward-running sentences. They seemed to have the typesetting equivalent of unlimited minutes when it came to using insulting synonyms found in the thesaurus. Their enemies were “depraved,” “worthless,” “vile,” “intemperate,” and “wicked.” Accusations of drunkenness were frequent (and accurate) as were charges of corruption and debauchery.

Thomas Jefferson testified to the ugliness of the trade when he described what he looked for in a good editor. He lamented that such a person would have to:

set his face against the demoralising practice of feeding the public mind habitually on slander, & the depravity of taste. … Defamation is becoming a necessary of life; insomuch, that a dish of tea in the morning or evening cannot be digested without this stimulant. Even those who do not believe these abominations, still read them with complaisance … [and] betray a secret pleasure in the possibility that some may believe them, tho they do not themselves.

This sounds just as high-minded as we’d expect from the author of the Declaration of Independence, but it’s blarney. Jefferson was fine with slander, feeding the public need for low entertainment and fact- free denunciations just as long as they were aimed at his rivals. He had no problem supporting or arranging to support newspapers that did just that.

Like today, in the age of our founders one person’s depravity and slander was another person’s fact. What Jefferson would have roared about, his rival Alexander Hamilton would have applauded as plain truth. Each side in the debates of the early republic thought they were the hero in the morality play of the infant republic.

Unlike the righteous, heated, and infantile debates of the social media age, the stakes in these verbal wars were high. These men thought they were determining the course of the nation and a free mankind—that gave them the excuse to employ any means to meet their ends. But there was a tension in this. If the presidency was to be run by virtuous statesmen, there was no greater test of that virtue than how those would be presidents behaved in their private acts. By funding the scandalmongers and encouraging them, Jefferson and others failed at what they would have said was the first test of character: doing the right thing when no one was looking. That they were doing so in order to make sure a man of virtue held the office doesn’t erase the offense.

When George Washington left the White House, he warned against the “spirit of party” that would turn the disputes between men like Jefferson and Hamilton into a permanent state of combat. It was too late; the debate between the Hamiltonian Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans over the best way to interpret the Constitution and the authority it gave to the federal government was well established. The argument formed the basis of America’s two-party system.

Callender sided with the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican Party, which believed in a limited federal government that would allow states to determine their own future. Republicans, as they were known until 1828 when they would become the Democratic Party, believed Congress had principal power in national affairs, since it was closer to the states and the people. A too-powerful executive, supported by a large army, would encourage monarchism. Republican distaste for the monarchy inspired their support for the freedom-loving revolutionaries in France over Great Britain’s king.

Hamilton aligned his thinking with the interests of the major trading centers of the Atlantic. He supported a stronger central government, because he believed that only the federal government could inspire the confidence necessary for a strong national economy spread over an extended geographical space.

Jefferson and Hamilton were both members of Washington’s Cabinet (the former was secretary of state, the latter secretary of the treasury), and they carried out their office disagreements through proxies. Hamilton supported the Gazette and Jefferson the Philadelphia National Gazette. “The Gazette of the United States and the National Gazette were conceived as weapons, not chronicles of daily events,” writes historian Burns.

Jefferson noticed Callender because he was on the hunt for allies in his battles against Hamilton and the Federalists in advance of the election of 1800. By the end of the Washington administration in 1796 there were scarcely 30 papers that could be classified as Republican, compared to about 120 that were Federalist.

Newspaper patrons like Jefferson built lists of subscribers, solicited donations, and provided anonymous tracts for publication. The secretary of state even leaked confidential documents to his favorite editor and begged his friend James Madison to attack Hamilton in print: “Nobody answers him, and his doctrines will therefore be taken for confessed. For god’s sake, my dear sir, take up your pen, select the most striking heresies, and cut him to pieces in the face of the public.”

Hamilton complained about Jefferson’s back-stabbing to President Washington. Jefferson wrote the president a 4,000-word defense in which he denied any involvement in newspaper writing so categorically he might as well have denied ever reading a paper. It was a lie, of course, wrapped in high-minded philosophical hand waving. As Si Sheppard details in his book on media bias, not only had Jefferson supported the opposition press, he’d written some of the articles himself.

Callender Undoes Hamilton

It should not surprise us that the man with the sandy hair and thoughts of Palladian architecture in his head met with the disreputable Callender in the Philadelphia print shop of Snowden and McCorkle in the summer of 1797. It certainly would have surprised the public, though. Callender had built his reputation, in part, on savaging the president for whom Jefferson had just served.

“If ever a nation was debauched by a man, the American nation has been debauched by WASHINGTON,” wrote Callender. “If ever a nation has suffered from the improper influence of a man, the American nation has been deceived by WASHINGTON. Let his conduct then be an example to future ages. Let it serve to be a warning that no man may be an idol, and that a people may confide in themselves rather than in an individual.”

Attacking Washington was just a starter course for Callender. The summer of his meeting with Jefferson, he was the talk of drawing rooms for what he had uncovered about Alexander Hamilton’s sex life.

Callender was different than other writers. He named names, dropping the convention of only using the first and last letters of a person’s name. According to Callender’s biographer Michael Durey, he had a “complex and contradictory character. He was self-righteous, strongly puritanical with regard to personal morals, insufferably proud, with a deep and abiding mistrust of human nature.”

Callender’s view was that only virtuous leaders could ensure the continued vitality of the republic, and only by incessantly watching them could their virtue be assured. His rival, Federalist writer William Cobbett, agreed, writing, “Once [a man] comes forward as a candidate for public admiration … every action of his life public or private becomes the fair subject of public discussion.”

What Callender uncovered started before he had even come to America. In 1792, the 36-year-old Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton started an affair with the 23-year old Maria Reynolds while his wife and children were away, the one dramatized in Miranda’s musical. Reynolds had claimed that her husband had abandoned her and her daughter, and she’d asked Hamilton for enough money to get to New York. “It required a harder heart than mine,” he wrote, “to refuse it to Beauty in distress.” When he delivered the money in person, Maria offered a quick repayment. “I took the bill out of my pocket and gave it to her,” Hamilton later wrote of the moment of his ruin. “Some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable.”

Reynolds’ husband, James, soon learned about the affair and initiated an extortion scheme. Or, as some have suggested, he initiated a long-planned extortion scheme that had been mapped out long before Maria Reynolds ever knocked on Hamilton’s door. Hamilton paid the notes and continued the affair through the end of the year. Ultimately Hamilton would pay nearly $1,000, about $24,000 in today’s dollars. On Dec. 15, 1792, future president James Monroe, then a senator from Virginia, learned of Hamilton’s payments to James Reynolds and confronted him. The information had come to Monroe from a Virginia prison cell, where Reynolds was serving time for another swindle involving unpaid wages to Revolutionary War veterans. Reynolds tried to limit his days on bread and water by trading information for a lighter sentence. He let it be known that he could “make disclosures injurious to the character of some head of a department.”

John Vanderlyn/National Portrait Gallery

Armed with the accusation, Sen. Monroe, Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg, and another member of Congress began a short, secret investigation. They accused Hamilton of using his position to enrich himself through speculation, and they threatened to tell the president. Enraged, the treasury secretary invited the three men to his house to show them letters that proved he was innocent of malfeasance. He had simply been guilty of adultery.

After a sweaty and tense exchange, the three men were satisfied. There was a wall between public and private life, and as public men it was in their interest to keep that wall strong. Though Monroe was a Jefferson ally in the daily newspaper battles against Hamilton, he and Jefferson didn’t use the material discovered in the private investigation. Monroe and his two colleagues put all papers related to Hamilton— including some of his correspondence with James Reynolds—in a safe place.

Not safe enough. Monroe said he had entrusted the correspondence to “a respectable person in Virginia.” Some historians believe it was Jefferson. He might have been responsible for ultimately leaking them four years later in 1796, but the consensus view is that the culprit was John Beckley, a Jefferson ally and clerk of the House. In 1796, Federalists had pushed Beckley from his post, and he wanted to get back at their leader Hamilton, so he leaked everything related to the affair to Callender.

The full story appeared in the History of the United States 1796, a dull name for a volume that like a brown wrapper obscured what was inside. “This great master of morality,” Callender accused, “though himself the father of a family, confess[ed] that he had an illicit correspondence with another man’s wife.” Callender labeled James Reynolds a “procurer” (a pimp) and said that since that was the lowest of all human character traits, Hamilton’s commerce with him, brought him lower than his mere adultery did.

Callender’s bigger charge was corruption. He didn’t buy Hamilton’s private excuse. “So much correspondence could not refer exclusively to wenching,” he wrote. “No man of common sense will believe that it did. Hence it must have implicated some connection still more dishonourable.”

Hamilton thought his public virtue on the question of financial corruption was all that mattered. So two months after Callender’s article he defended himself against the corruption charge with a 95-page pamphlet that foreshadowed its cumbersome argument with the winding-road title Observations on Certain Documents Contained in No. V & VI of “The History of the United States for the Year 1796,” in Which the Charge of Speculation Against Alexander Hamilton, Late Secretary of the Treasury, Is Fully Refuted. Written by Himself.

Hamilton denied any improper speculation with James Reynolds but confessed “my real crime … is an amorous connection with his wife.” The old codes of honor that had governed the private affairs of men were being undone by the new political system fed by the popular press. Hamilton would get caught between the two. He had been exonerated by the small group of three lawmakers, but when his sins became public, he was vilified. Hamilton warned if this trend continued, “the business of accusation would soon become in such a case, a regular trade, and men’s reputations would be bought and sold like any marketable commodity.”

Hamilton misread his audience. “You have widened the breach of dishonor by a confession of the fact,” one New Yorker told him. Republican papers said he was trying to legitimize adultery, that he had “violated sacred promises.” They railed against the injury he did to his wife by his admission, and concluded, as public moralists often do today, that to be dishonest in one sphere is necessarily to be dishonest in another. “If a man will rob his family of their peace, and enjoyment, if he will abandon himself to the vilest connections; if he will place daggers in the breast of a virtuous wife, and stab the reputation of his children, where are the bonds of honor to vouch for his fidelity in any other transaction?”

The Federalists came after Callender with a hammer. “In the name of justice and honor, how long are we to tolerate this scum of party filth and beggarly corruption, worked into a form somewhat like a man, to go thus with impunity?” said the Gazette of the United States. “Do not the times approach when it must and ought to be dangerous for this wretch, and any other, thus to vilify our country and government, thus to treat with indignity and contempt the whole American people, to teach our enemies to despise us and cast forth unremitting calumny and venom on our constitutional authorities?” The publication suggested that Callender’s behavior had made him entitled “to the benefit of the gallows.”

Savior Jefferson

The pressure from the Federalists drove Callender from Philadelphia and into Jefferson’s Virginia. Callender was gleeful about what he had goaded Hamilton into. “If you have not seen it,” he wrote Jefferson, “no anticipation can equal the infamy of this piece. It is worth all that fifty of the best pens in America could have said against him.” This blow was about more than a simple presidential election. In an ideological battle for the direction of the new country Callender had struck mute the most articulate advocate for the other side. If Jefferson had been as concerned about the press as he said, he should have been repulsed by Callender’s behavior, even if it did undermine a rival. Instead, he was drawn to Callender, supporting him as he headed south by foot.

On July 13, 1798, Callender set out. His wife had just died from yellow fever. He was penniless, reportedly feeding himself and his children on “broken victuals” from a wealthy neighbor and relying on small donations from acquaintances to buy firewood and snuff. Assassins had visited his house on two different occasions, he said, though given his reputation for befouling the truth, that could mean that none had visited at all. During his trek south, Callender learned he was still being hunted. He had to turn down an ally’s offer of a carriage for fear that would make it easy for villains to spot him. So he walked—or, more accurately, he weaved. Outside of Leesburg, Virginia, he was arrested, drunk and loitering outside of a local distillery (perhaps trying to get a contact high). He was charged with vagrancy. Newly installed in Virginia, Callender complained to Jefferson that Republicans owed him. He also simpered that he was “belied and stared at, as if I was a Rhinoceros,” escalating his bath of self-pity to exclamations that “I am in danger of being murdered without doors.” Jefferson loaned him $50, which helped him get on his feet until he could secure a place at the Richmond Examiner, edited by Jefferson’s close associate Meriwether Jones.

Jefferson continued to loan Callender money and asked his friends to do the same, arguing to Madison that it was “essentially just and necessary” that Callender should be aided. Jefferson also sent Callender encouraging letters elevating his sufferings. “The violence which was mediated against you lately has excited a very general indignation in this part of the country,” Jefferson wrote about the arrest outside the distillery. Letters like this deepened Callender’s fondness for the master of Monticello.

The Prospect Before Us

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Official presidential portrait of John Adams by John Trumbull, 1792. The Prospect Before Us, by James T. Callender. Printed for the author by M. Jones Jr., and J. Lyon, 1800. Article snippet from Farmers’ Museum Literary Gazette, Aug. 3, 1802, p. 2.

In the election of 1800, President Adams defended his tenure against Vice President Jefferson, who had won office in one of the last elections in which the vice presidency went to the runner up. It was a test of whether the new nation could hand over power peacefully between two factions. Or would the faction in charge use the tools of power for personal ends, corrupting the experiment so soon after it had started? Jefferson had said to Adams, “Were we both to die today, tomorrow two other names would be put in the place of ours, without any change in the motion of the machinery,” which was how it was supposed to work. But that machinery hadn’t been tested, and everything about the election of 1800 suggested that both sides were trying to tear down the leaders of the opposite party with the implicit view that were they allowed to succeed, they would destroy the machinery.

Neither Jefferson nor Adams campaigned for the job outright, but both urged friendly writers to support them in the papers. Jefferson and the Republicans set up a “correspondence committee” to write friendly articles for the papers. He helped to distribute the writings, including purchasing some papers in bulk and making sure they were put in the hands of influential gentlemen who could spread the information. “This summer is the season for systemic energies and sacrifices,” wrote Jefferson to Madison. “The engine is the press. Every man must lay his purse and his pen under contribution.”

Callender was crucial in this campaign, trading secret letters with Jefferson, who did not sign his: “You will know from whom this comes without a signature.” Secrecy was crucial, as Callender’s biographer Durey points out, because “evidence that Jefferson was supporting from his own purse the notorious defamer of Washington, Adams, and Hamilton would have destroyed his carefully constructed image of being above base party intrigues.”

Callender, a writer of such drive that he often talked about scrawling himself into headaches, wrote a 183-page pamphlet The Prospect Before Us in which he savaged the incumbent: “the reign of Mr. Adams has, hitherto, been one of continued Tempest of malignant passions.” The author was kind enough to send a copy to the president. Future historians, he predicted, “will enquire by what species of madness America submitted to accept, as her president, a person without abilities, and without virtues: a being alike incapable of attracting either tenderness, or esteem.” Callender didn’t limit his attacks to the simply professional, calling Adams “a hideous hermaphroditical character which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” “Take your choice,” Callender wrote, “between Adams, war, and beggary, and Jefferson, peace, and competency!”

The harangue pleased Jefferson, who wrote to Callender that the book “cannot fail to produce the best effect.” Given that Adams and Jefferson had been friends, this was extraordinary. Jefferson had once written Adams “The departure of your family has left me in the dumps.” Now he was helping orchestrate his downfall.

The Federalists returned fire, spreading rumors that Jefferson was an atheist from whom the God-fearing would have to hide their bibles. “Should the infidel Jefferson be elected to the Presidency,” said the Hudson Bee, quoting another Federalist paper, the New England Palladium, “the seal of death is that moment set on our holy religion, our churches will be prostrated, and some infamous prostitute, under the title of the Goddess of Reason, will preside in the Sanctuaries now devoted to the Most High.”

Stop Callender Now

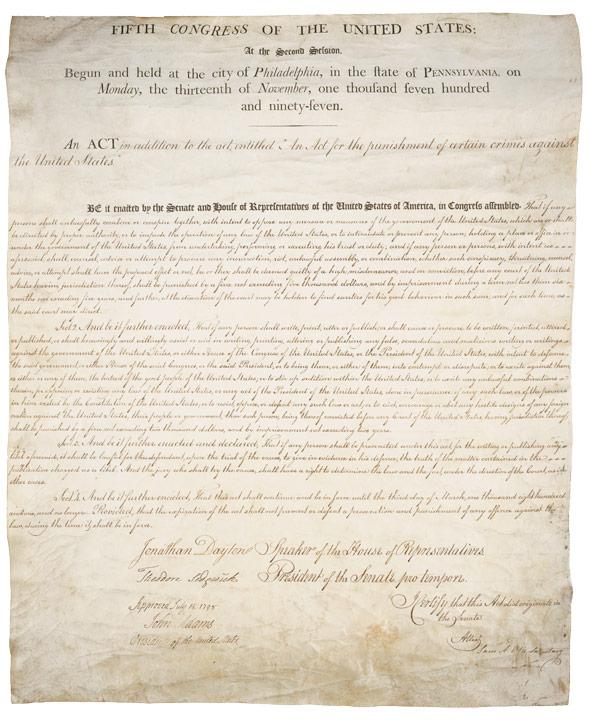

Callender’s writings were so hot, President Adams came after him. In July 1798, Congress gave Adams a new weapon: the Sedition Act, which criminalized making false statements that were critical of the federal government. Federalists wrote the legislation in a desperate act to muzzle the Republican newspapers that had been beating them so thoroughly. Republicans howled, not only because it was an attack on their voices but also because it was a constitutional overreach that smacked of monarchical control.

Jefferson railed against the act as “an experiment on the American mind to see how far it will bear an avowed violation of the constitution.” This was the corruption that Republicans had worried about. Those in power would overthrow the Constitution to keep themselves in power. This wasn’t just a fight over personal ambition, it was a precedent- setting moment for the new nation, said Jefferson: “If this goes down, we shall immediately see attempted another act of Congress, declaring that the President shall continue in office during life, reserving to another occasion the transfer of the succession to his heirs, and the establishment of the Senate for life.”

The Sedition Act is considered one of the great mistakes of the early republic—Callender was the last person prosecuted under the law, and Congress would repudiate it publically many years later. It is possible to see how Federalists could get worked up enough to support such a law. The newspaper accounts weren’t just full of mean philippics that hurt people’s feelings. To some, they were a danger to the entire system. They elevated partisanship over truth, self-dealing over selfless virtue. Ugliness in politics may always have been with us, but as the country was taking its first steps, the bile was considered a dangerous poison.

Sedition Act of 1797. United States federal government.

The Sedition Act seemed designed to capture Callender, and on May 21, 1800, it did. Exactly seven years after he arrived in America on the run from sedition charges and celebrating that he could say anything, Callender’s pen sent him to the pen.

At the trial, the scribe faced notorious Adams partisan and Federalist circuit justice Samuel Chase, who brought his righteous fire to Richmond in the hopes of locking Callender away. Chase made sure the jury was packed with local Federalists. Jefferson and the Republicans rallied to Callender’s cause. Jefferson made sure his three defense attorneys were some of the state’s most prominent lawyers, including the state attorney general. They all served without pay, which indicates how seriously the Republicans took the matter.

The indictment accused Callender of defaming the president: “Can any man of you say that the president is a detestable and criminal man,” asked Chase, and “excuse yourself by saying it but mere opinion?” Callender claimed his opinions didn’t need to be backed at every turn: “If it shall be insisted, that I aver what I have not proved, I answer, that for many averments regular proof is not required. Common report is sufficient.” Chase had an easy time of it. The government did not have to prove that the seditious writings were false. Instead, the accused had to disprove the charges against him—a total reversal of the principles of justice upon which the American system was based.

Callender’s lawyers tried to challenge the constitutionality of the Sedition Act before the jury. Chase called their argument “irregular and inadmissible.” The defense was not going to win, and in the end Chase convicted and sentenced Callender to nine months in jail and a fine of $200, asserting that Callender in attacking Adams had made “an attack up on the people themselves.”

Behind bars, Callender taunted the judge by continuing to write. He entitled one new chapter “More Sedition” and attacked Adams as “insolent, inconsistent, and quarrelsome to an extreme. … Every inch which is not full is rogue.” Transcripts of his trial were also published, adding to his notoriety.

Republicans rallied to Callender’s cause as a symbol of the egregious villainy of the Sedition Act and the Federalists who supported it. Jefferson wrote to his scribe in jail offering sympathy and consolation for the man whose “services to the public liberty” he had praised.

Who Is This Callender You Speak Of?

Collection of the New Jersey Historical Society

The presidency and the new republic survived the test of the election of 1800. Despite the daily warfare between the two parties, power was transferred peacefully from the Federalists, who had been founded under Washington, to the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans. But there was a wrinkle—a conflict not between the parties but between Republican rivals. Presidential electors were given two ballots to cast for two candidates for president. The greatest vote getter would become the president, and the No. 2 finisher would be appointed to the vice presidency. Adams lost, but electors who voted for Jefferson also voted for Aaron Burr, which meant in the end the two men were tied. Republicans had voted with the expectation that Jefferson would be the president. Burr had said if there were a tie, he would obviously step aside. “It is highly improbable that I shall have an equal number of votes with Mr. Jefferson, but if such should be the result, every man who knows me ought to know that I should utterly disclaim all competition.” But when there was a tie, and the election was sent into the House of Representatives, Burr didn’t step aside. House members voted repeatedly and neither man could win a majority. It took 36 ballots before Jefferson could win a majority and be declared the new president. Alexander Hamilton had helped break the deadlock, expressing his support for his old enemy Jefferson over his even greater rival Burr. He had particular sway, because the Congress that was voting to select the new president was the sitting one, controlled by Federalists, not the Republican one that would come in as a result of the 1800 election.

Hamilton told his friend Oliver Wolcott Jr. that Jefferson “is by far not so dangerous a man and he has pretensions to character.” Those pretensions to character had not kept Jefferson from supporting the newspapers that ruined Hamilton and fought his cause at every turn, but never mind. Hamilton concluded that Burr was even worse, “far more cunning than wise, far more dexterous than able. In my opinion he is inferior in real ability to Jefferson.”

No one was more delighted than Callender that Jefferson won the election of 1800. “Hurraw!” he yelped. “How shall I triumph over the miscreants! How, as Othello says, shall they be damned beyond all depth!” At toasts to Jefferson’s victory, he was celebrated. “To James Callender,” said Capt. Edward Moore, lifting a glass at Richard Price’s tavern in Albemarle County, “who looks down on his persecutors with their merited contempt.”

As president, Jefferson immediately distanced himself from Callender. He pardoned him along with all others convicted under the Sedition Act, but Callender wanted more in return for all he’d done. He needed that $200 fine back, and he wanted to be elevated to postmaster of Richmond. Jefferson, who had been chatty, suddenly stopped responding to letters. Callender got antsy. “By the cause, I have lost five years of labor; gained five thousand enemies; got my name inserted in five hundred libels …”

This letter also received no reply. By Sunday, April 12, 1801, Callender wrote Madison that he was “hurt” by the “disappointment” of not having his fine repaid. “I now begin to know what ingratitude is,” he wrote, sounding more and more like a jilted lover.

It’s not hard to understand why Callender was being put in the spam folder. Jefferson and his allies didn’t want to associate with someone as unpredictable as Callender once they were in power. They certainly didn’t want to give him a patronage job. “Callender was already too well known, and too much despised to be thought worthy of public trust: and Mr. Jefferson disdained employing any person who was unworthy,” wrote Meriwether Jones.

According to Jefferson biographer Jon Meacham, Jefferson wrote off Callender because “rising men do not like to be reminded of the smell of the stables.” Jefferson didn’t want to be reminded that he’d used the low road to get to high office.

Angry that he wasn’t getting the responses he wanted, Callender traveled to Washington to meet with Madison. “The money was refused with cold disdain, which is quite as provoking as direct insolence,” Callender wrote of his request for payment. “Little Madison … exerted a great deal of eloquence to show that it would be improper to repay the money at Washington.”

Madison briefed the president, who dispatched Meriwether Lewis on May 28, 1801, to give Callender $50 to tide him over until the fine could be repaid in full. Callender’s attitude toward Lewis, who Jefferson would later send to explore the Northwest Territory, suggested that Jefferson might well have a larger problem than he realized. “His language to Capt. Lewis was very high toned,” Jefferson wrote Monroe in an account of the meeting. Callender threatened to release letters showing that he had colluded with Jefferson in attacking Adams. “He intimated that he was in possession of things which he could and would use of a certain case: that he received the [$50] not as charity but as a due, in fact as hush money.”

Jefferson’s African Queen

Sen. John Taylor had warned Jefferson years before that Callender might turn on him. “Upon any disappointment of his expectations,” he wrote, “there is no doubt in my mind, from the spirit his writings breathe, that he would yield to motives of resentment.”

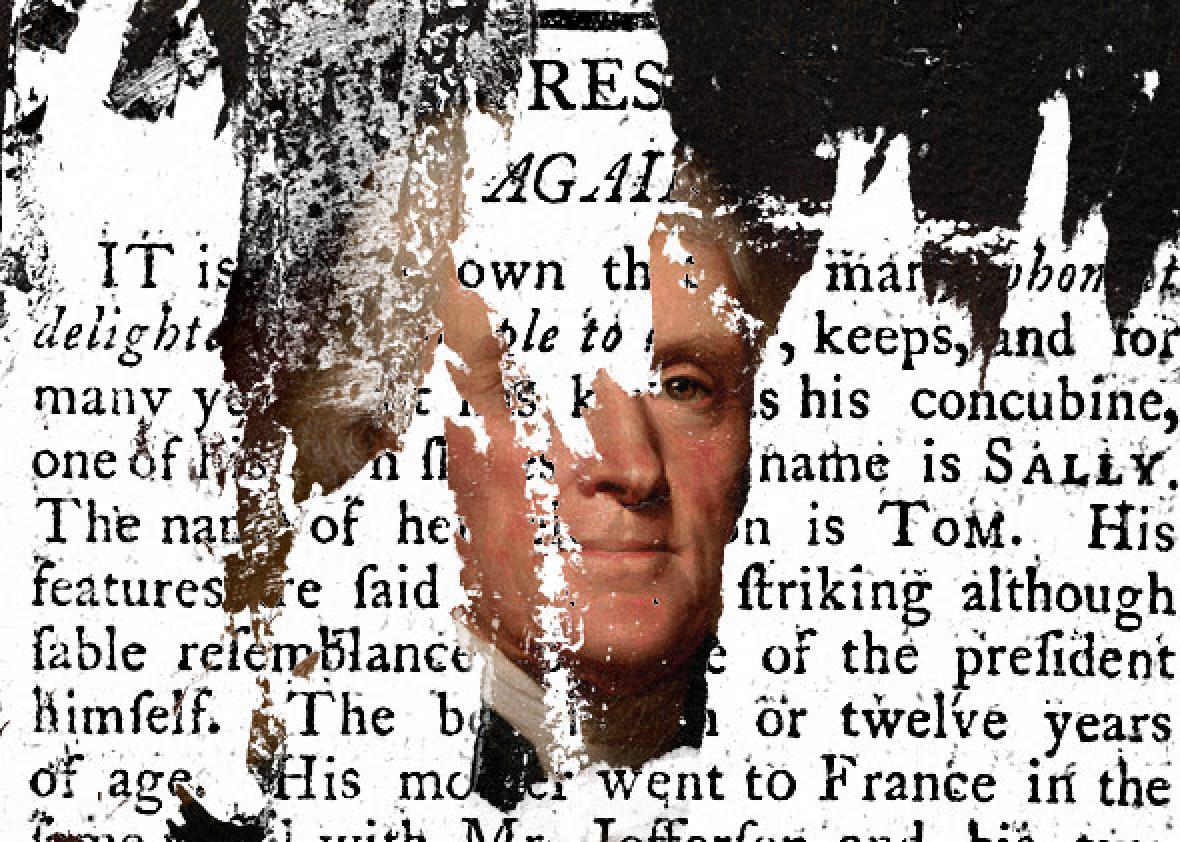

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Official presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800. Newspaper clipping from the Recorder, Sept. 1, 1802, p. 2. Library of Virginia.

Callender had always been motivated by revenge, and it would sober him up this time, too. He raged back to Richmond and helped establish the Richmond Recorder, dedicated to attacking Jefferson and the hypocrites of the Virginia aristocracy. He took on the gamblers and duelers and slave owners who fathered children with their slaves who all pretended, as members of the Virginia gentry, that they did none of those things.

Callender started slowly at first on Jefferson. He pointed out that the president had praised him for his writings and supported him financially. He quoted liberally from Jefferson’s letters as proof. Hamilton’s newspaper, the New York Evening Post, published Callender’s articles and accused Jefferson of inciting Callender to expose Hamilton’s affair with Maria Reynolds. “I am really mortified at the base ingratitude of Callender,” wrote Jefferson to Monroe. “It presents human nature in a hideous form. It gives me concern, because I perceive that relief, which was afforded him on mere motives of charity, may be viewed under the aspect of employing him as a writer.”

The claim of simple charity is hard to support, given the letters that are now public. Jefferson explained himself to Abigail Adams, who had written him to claim a “personal injury” at the disclosure that he had supported this man who had attacked her husband so relentlessly. Jefferson pleaded that “nobody sooner disapproved of [Callender’s] writing than I did,” which is a bracing lie. There’s not one word of censure in the Jefferson and Callender correspondence. There is however, encouragement and easy familiarity.

Republicans in Philadelphia attacked Callender to discredit anything he might write in the future. Future Treasury Secretary William Duane wrote that Callender’s wife had died from a sexually transmitted disease “on a loathsome bed, with a number of children, all in a state next to famishing … while Callender was having his usual pint of brandy at breakfast.” This was not wise. In retaliation, Callender went nuclear. After his disastrous meeting with Madison, Callender had written, “Black Sally was fluttering at my tongue’s end; but with difficulty I kept it down.”

The Recorder, Sept. 1, 1802, p. 2. Library of Virginia.

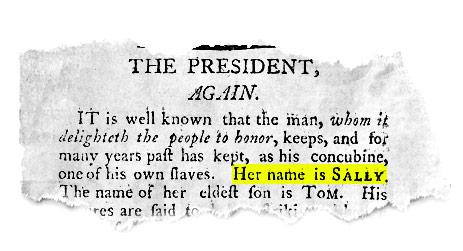

That was a reference to Sally Hemings, Jefferson’s slave and mistress. On Sept. 1, 1802, Callender no longer held his tongue:

It is well known that the man, whom it delighteth the public to honor, keeps, and for many years has kept, as his concubine, one of his slaves. Her name is SALLY. The name of her eldest son is TOM. His features are said to bear a striking although sable resemblance to the president himself. … By this wench, Sally, our president has had several children. … THE AFRICAN VENUS is said to officiate, as housekeeper, at Monticello.

Callender argued that “the public have a right to be acquainted with the real characters of persons, who are the possessors or the candidates of office.” It was hard for Republicans who had made such use of Callender’s attacks on Hamilton to disagree. In signing off his piece, Callender let Jefferson know that he had done this to himself. “When Mr. Jefferson has read this article, he will find leisure to estimate how much has been lost or gained by so many unprovoked attacks upon J.T. Callender.”

Callender’s End Date

Unlike Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson did not answer the claims about Sally Hemings. Callender wrote about it repeatedly and subscriptions grew, but eventually he could not top his blockbuster story. An ongoing fight with the paper’s publisher (which included charges that Callender had sodomized his brother), and constant threats to his safety by Republicans, put Callender more and more in a mood to drink. To be sober, said the Recorder’s publisher, was for him to be drunk only once a day and that his normal drink would fell two grown men. The stories of his antics while pickled mounted; according to one story, he stumbled into his host’s bedchamber in the middle of the night to demand that a servant be whipped.

Examiner, July 27, 1803

Jefferson’s ally Meriwether Jones wrote in his diary, “Are you not afraid, Callender, that some avenging fire will consume your body as well as your soul? Stand aghast thou brute, thy deserts will yet o’ertake thee.”

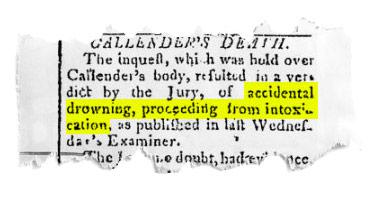

In the end, it wasn’t fire, but water. Early in the morning of Sunday, July 17, 1803, Callender was observed wandering the town in a drunken stumble. Soon after, his body was found floating in the James River. He appeared to have drowned in a very shallow amount of water. A doctor “tried every method to restore him to life—but all his efforts proved ineffectual.” After a brief coroner’s inquest, which recorded accidental drowning while drunk, Callender was buried that same day in the local church yard. As Durey writes, “It was as if the citizens of Richmond could not wait to destroy all evidence of his existence.”

A scoundrel and a drunk, James Callender has long been treated as a historical cur, but the chaos he unleashed in both parties uncovered the truth that the men of virtue who founded the country were not as virtuous as they pretended, either in their private lives or in the way they carried out their public debates. Thomas Jefferson, in particular, was willing to endorse, finance, and encourage the basest personal attacks on his rivals while bemoaning the coarse nature of the public press. It was a hypocrisy that swelled until Thomas Callender punctured it. A country moving toward popular sovereignty was destined to have more of these clashes, as the habits of the elites were brought to the public by the press. Callender also codified an important maxim of politics: If you’re going to get an attack dog, keep him well fed.