Membership in a political party that had prevailed in only two presidential races out of the last nine and was divided on matters both trivial and ideologically significant. Party rules that required a large majority of delegates to gain nomination. A reputation as a lightweight flip-flopper who went back on his word. Despite all of these obstacles, in 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt became the last candidate to emerge from a brokered convention and win the presidency. How did he do it?

Roosevelt’s involvement in presidential politics began in 1920. The Democrats named the 38-year-old, whose most high-profile previous appointment was as Woodrow Wilson’s assistant secretary of the Navy, as their vice presidential nominee on the 1920 ticket alongside Ohio Gov. James M. Cox. Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge won decisively that year. The Republicans also carried both houses of Congress. This was a political catastrophe for Cox but gave Roosevelt—a handsome, charismatic, wealthy New Yorker with an easy charm and a beloved last name—a chance to introduce himself to a wider audience.

But then FDR, vacationing in New Brunswick, Canada, at his family’s cottage in the summer of 1921, came down with polio. As the months after the initial illness passed, it became clear that the next few years would have to be devoted to physical rehabilitation. The setback turned into an opportunity for Roosevelt to retreat at a time when his party was adrift. “If a Democrat with presidential ambitions had to come down with the disease, he couldn’t have chosen a better time than the early 1920s,” writes historian H.W. Brands. “The decade after the World War was a wilderness period for the Democrats,” pulled between the Tammany bosses of New York City, who were “wet” (i.e., for the repeal of Prohibition), pro-immigration, and economically conservative, and Southern racists, who were dry, anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic, “with western mavericks shouting from the sideline.”

While recuperating, FDR managed to keep himself in the public eye through his charitable work with the Warm Springs Foundation, a therapeutic center for polio sufferers in Georgia; appearances at fundraisers for the Democratic Party and organizations like the Woodrow Wilson Foundation; and regular correspondence with party leaders and political allies from the Wilson years and the 1920 presidential campaign. In 1924, the year of the party’s disastrously drawn-out “Klanbake” convention at Madison Square Garden, Roosevelt was one of the only people in the party to emerge looking good; his speech nominating Al Smith—the Catholic governor of New York with an appealing rags-to-riches life story—was a hit. In 1928, FDR again went to the Democratic convention and delivered the nominating speech; this time Smith was nominated on the first ballot. Smith, in turn, drafted Roosevelt to run to replace him as governor of New York; Roosevelt was reluctant but eventually agreed in order to retain party support for his presidential ambitions.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, as he thought more and more about a presidential run, Roosevelt tried a few strategies to pre-emptively address any concerns about his physical fitness. The conventional wisdom that FDR hid his paralysis from the public is, as Christopher Clausen writes, exaggerated; FDR’s mobility limitations were common knowledge at the time. In July 1931, the probable candidate sat for an extensive interview with Liberty magazine, which resulted in an article headlined “Is Franklin D. Roosevelt Physically Fit to Be President?” Roosevelt was photographed with his leg braces, and in the springs at Warm Springs; he was examined by a trio of doctors—an orthopedist, a neurologist, and a general practitioner—and was candid with the interviewer, Earle Looker. “As for his limited mobility,” Clausen writes, “he portrayed it as an advantage on the job; it forced him to concentrate.”

Though the Democratic Party struggled during this period, by 1931 the Depression had made Herbert Hoover wildly unpopular, and the White House finally seemed within the party’s grasp in the 1932 election. As such, possible nominees came out of the woodwork. Among them was Al Smith, who had lost the 1928 election by a landslide. Smith had come to feel personally affronted by Roosevelt’s rise in New York politics and irritated that he wasn’t more often consulted or considered by the wildly popular governor. Smith didn’t announce his candidacy for the nomination in 1932—at that time, candidates didn’t need to formally declare during the primary season—but instead let it be known that he would (as the New York Times put it) “place his cause in the hands of the people and risk his chances without making an active campaign for the nomination.”

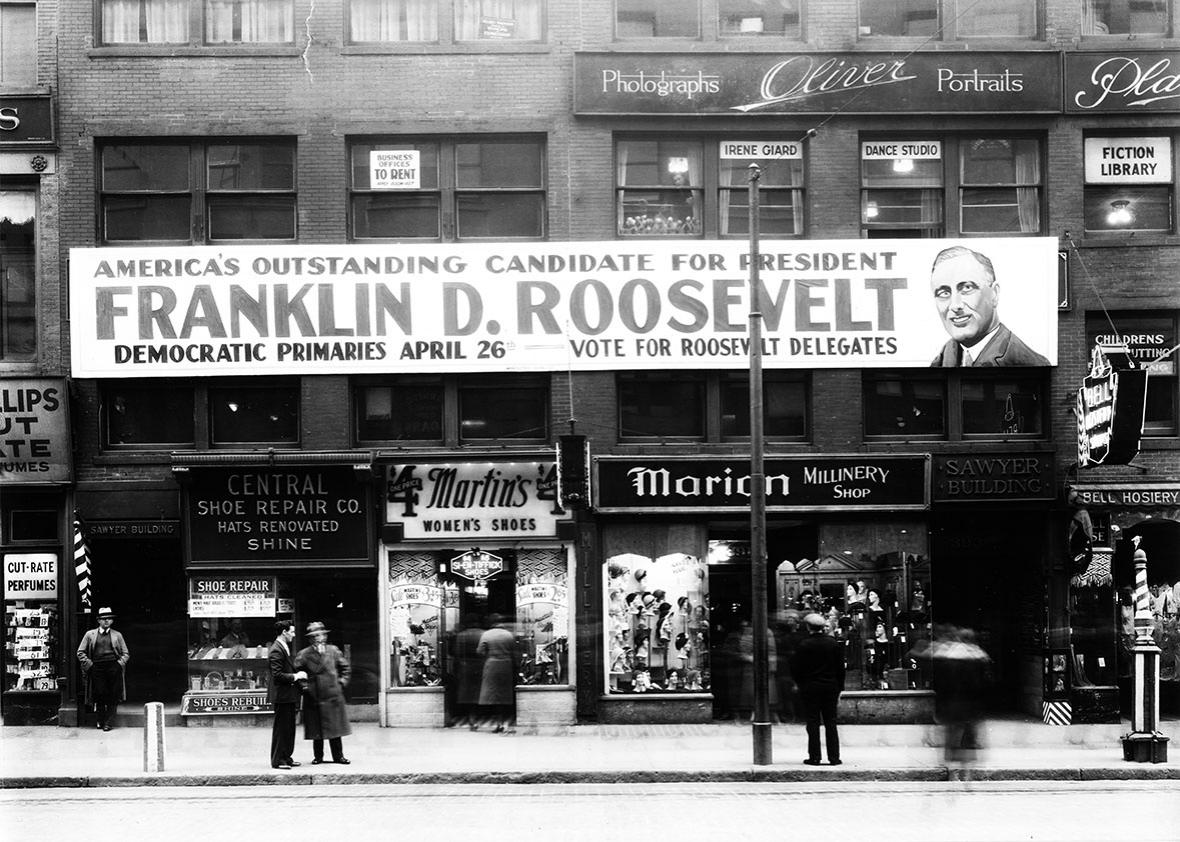

Today’s lengthy primary season is a creature of the postwar era; the Democrats held only 17 primaries in 1932. Because it wasn’t traditional for candidates to campaign in the primaries in person, Roosevelt didn’t leave his job and home in New York to petition for votes in the 14 primaries he entered. On the strength of his undeclared campaign, Smith defeated Roosevelt in Massachusetts and New York (and won in New Jersey, a primary Roosevelt did not enter). The Texan Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, riding on the strong endorsement of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, carried California—a disheartening defeat for Roosevelt—and Ohio and Illinois went to favorite-son candidates. The vote was split enough to guarantee a brokered convention; FDR’s camp arrived in Chicago with a majority of delegates but not enough to guarantee him the nomination.

Despite his earlier PR efforts, FDR’s health was an issue in the 1932 race. His opponents talked about how bad his paralysis actually was, whispering about whether he would be able to carry out a successful campaign. But FDR’s possible lack of physical vigor wasn’t the only objection to his candidacy. Steven Neal writes that FDR wasn’t wet enough for influential big-city bosses, who wanted a repeal of Prohibition so that they could profit from liquor licenses. Big business—banks and utilities—worried that he would intervene in the economy, to their detriment. And it wasn’t just party stalwarts and businessmen who stood in opposition to his nomination; influential pundits like Walter Lippmann, H.L. Mencken, and Heywood Broun argued against his candidacy as well. Lippmann wrote of the former assistant secretary of the Navy and second-term governor of New York: “He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president.” Broun dubbed him “Feather Duster Roosevelt”: a real lightweight.

Those who weren’t convinced of Roosevelt’s essential triviality were worried that he was too far left for a party that had supported many progressive and internationalist social programs under Woodrow Wilson but also harbored a sizeable contingent of people who were economically conservative, isolationist, and segregationist. Historian Donald S. Rothchild describes FDR’s ideology in the early 1930s as a blend of Theodore Roosevelt’s and Wilson’s brands of early-20th-century progressivism: “In repeated speeches he stressed the need for improving the conditions of the farmer, lowering tariffs, curbing the power of the government to infringe on the rights of the individual, honesty and integrity in law enforcement, conservation of national resources, and cooperation with other nations.”

In one of FDR’s campaign radio addresses, delivered in April 1932 and written by Raymond Moley, one of the three Columbia professors FDR had recently assembled in his famous “Brain Trust” to help him plan solutions to the Depression, the candidate spoke frankly about the class divide in the United States. FDR argued that plans to ameliorate the Depression needed to “build from the bottom up and not the top down…[to] put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.”

Because of speeches like this one, writes historian Patrick J. Maney, Democrats like John Jacob Raskob, the party chairman, “considered [FDR] to be an out-and-out radical” and sought to block his nomination. Al Smith responded to Roosevelt’s “bottom up” speech with fire: “I will take off my coat and vest and fight to the end against any candidate who persists in any demagogic appeal to the masses…to destroy themselves by setting class against class and rich against poor.”

Keystone-France/Getty Images

FDR came into the convention with about 600 delegates, most from the Deep South, New England, and the farming states of the West, where rural voters had responded to Roosevelt’s record as the first governor to take significant action to relieve the suffering caused by the Depression. But he needed 770 votes to secure the two-thirds majority required by party rules at the time. Al Smith was probably the biggest threat to Roosevelt’s nomination. Before the convention proper, financier Bernard Baruch brokered a meeting between Smith and William Gibbs McAdoo, former rivals in the 1924 nomination race, who agreed to collude in order to stop Roosevelt. Though McAdoo, son-in-law of—and secretary of the Treasury under—Woodrow Wilson, had failed to land the Democratic presidential nomination in 1920 and 1924 and had not entered any of the primaries in 1932, he was still (as historian Russell Posner writes) “active and vigorous at 69” and “anxious to return to politics.” McAdoo thought he might be able to gain some traction as a dark horse in Chicago, and so was willing to plot with Smith to stop FDR.

Roosevelt had his own crack team of plotters. His co-campaign managers in 1932 were Louis McHenry Howe, a former reporter and editor who had started working with Roosevelt way back in 1912, and James Aloysius Farley, who managed FDR’s campaigns for New York governor in 1928 and 1930 and was the chairman of the New York State Democratic Party. Farley and Howe were loyal and energetic organizers and entered the convention week in high gear. Howe, in particular, was “frantic with suspicion and worry,” historian Alfred B. Rollins Jr. writes, desperate to nail down every detail in order to retain and woo delegates.

Howe’s best strategies exploited one of FDR’s strengths: his personable voice and manner. The candidate himself would remain at home in Albany, as per the tradition of the time, but Howe came up with several technological remedies for that distance. Before the convention, Rollins writes, Howe mailed every committed Roosevelt delegate a signed portrait and “a one-and-half-minute phonograph record with a personal message from the Governor.” The operative arranged security for the Roosevelt camp in the Chicago Convention Hall and the Congress Hotel, putting a loyal switchboard operator in place to man the phones the Roosevelt team would be using, for fear of eavesdroppers carrying information to opposing camps. (“Secretaries,” Rollins writes, “were briefed on the dangers of dating men who might be working for a rival.”) Farley brought delegates to Howe’s rooms, where Roosevelt spoke with them over the telephone, trying to solicit their support. Howe had a huge card file on the delegates who weren’t pledged to Roosevelt, which he hoped to use in order to sway them at key moments. (Howe’s card on Texan Jesse Jones: “Money—Houston Chronicle, owner of—For himself first, last, and all the time—Ambitious—Promises everybody everything—Double-crosser.” )

Imagno/Getty Images

Before the delegates even voted for a nominee, the Roosevelt group faced a few preliminary tests. First was a fight over changing the rules of the convention to eliminate the two-thirds policy, which would have allowed the candidate with a simple majority of delegates to carry the day. (Roosevelt eventually lost that one.) Second was the battle over the chairmanship of the convention. (Roosevelt’s man, Sen. Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, won.) Third was the platform, which Rollins calls “a striking Roosevelt victory,” including mention of “public works, federal relief, unemployment and old age insurance, regulation of the financial markets and of public utilities, conservation programs, and ‘a continuous responsibility of government for human welfare.’”

The chairmanship and the platform were victories for FDR, but they weren’t enough to hand him the nomination. Journalist H. L. Mencken was on-hand in Chicago, sending dispatches back to the Baltimore Evening Sun. On July 1, Mencken, who had opposed the Republican presidents of the 1920s but who thought the governor of New York was unproven, weak, and a bad choice for the Democratic nomination, wrote that the Roosevelt managers’ plan “to rush the convention and put over their candidate with a bang” had failed. Jonathan Alter writes that Smith, a famous wet, gave a speech advocating the repeal of Prohibition and that the oration was a barnburner. Anton Cermak, Chicago’s mayor and an opponent of Prohibition, had made sure the hall was full of people who would cheer Smith. This enthusiasm for an issue that FDR preferred to downplay was discouraging.

The situation was chaotic. “Howe and his FDR lieutenants did not have control of the floor,” Alter writes. Though Roosevelt had long been careful to walk a fine line in relation to the powerful New York political machine of Tammany Hall—neither condemning nor overtly supporting it—Smith’s enmity had helped earn him the opprobrium of the entire New York delegation, which should have been his home crowd. “FDR was trapped in the squishy middle,” Alter writes, “not pro-Tammany enough for New York; not anti-Tammany enough for reformers elsewhere.” The huge New York contingent refused to allow Roosevelt’s own campaign manager, the chairman of the state’s Democratic Party, a seat among the delegates.

The Roosevelt strategy was, at first, to push for balloting to happen as soon as possible, but when Howe and Farley perceived they had less support than they had thought, they instead began to play for time. Mencken, sitting in observation, found himself severely tried by the array of “rhetoricians and rooters” who got up to give speeches, calling the roster “depressingly typical of a Democratic national convention.” Two delegates died in the extreme heat of the hall, Mencken reported.

The first ballot finally began at 4:28 a.m. on July 1, and the results showed Roosevelt still 104 votes short of the nomination. “The second ballot,” which began at 5:17 a.m., “probably took more time than any ever heard of before, even in a Democratic national convention,” Mencken, who was a veteran of the 1924 fiasco, wrote. Just recording the votes consumed three hours. “The all-night session was a horrible affair, and by the time the light of dawn began to dim the spotlights, a great many delegates had gone back to their hotels or escaped to the neighboring speakeasies,” Mencken wrote. “When the balloting began shortly after 5 am scores of them were missing,” causing delays and debates over the “rights and dignities of alternates.” The results were scattered; vaudeville cowboy Will Rogers got 22 votes on the second ballot, recalling his famous post-1924 quip: “I am not a member of an organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

On the third ballot, which the anti-Roosevelt forces pushed to hold immediately in hopes of breaking his support, Roosevelt almost lost it all. FDR biographer Jean Edward Smith writes that on this ballot, the crucial decision came down to the Mississippi delegation, which had given its 20 votes to Roosevelt under the unit rule—the party obliged state delegations to vote as a bloc—but was deeply divided and threatened to break away from the candidate. Eventually Huey Long, then the governor of Louisiana, “jumped into the breach,” berating Mississippi Gov. Martin Sennet Conner, who supported Newton Diehl Baker Jr., Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of war: “You break the unit rule, you sonofabitch, and I’ll go into Mississippi and break you.” The threat worked, and the Roosevelt lines held, though the candidate was still short of a two-thirds majority.

The convention adjourned, promising to reconvene in the evening for the fourth ballot. Posner writes that Farley and Howe assessed the situation and decided that there was no way Al Smith’s delegates were going to jump ship. The Ohio and Illinois blocs pledged to their respective “favorite sons” would “hang on grimly in hopes of a ‘dark horse’ nomination.” That left the California and Texas delegations, currently pledged to Garner, as their best options.

Approaching Garner through two separate Texas allies, the Roosevelt camp offered the speaker the vice presidential nomination if he would withdraw and encourage the California and Texas Garner delegates to vote FDR. Meanwhile, William Randolph Hearst, monitoring the proceedings from California, decided that Garner, his chosen candidate, couldn’t win. Hearst preferred to support Roosevelt rather than see a dark horse carry the day. For Hearst, internationalism was the worst possible ideological commitment in a candidate; earlier in the campaign FDR had uneasily and halfheartedly walked back his Wilson-era belief in the League of Nations, which meant Hearst favored him over other remaining candidates, like committed internationalist Newton D. Baker. (A phone call from Joseph P. Kennedy, an early FDR supporter, played a role in convincing Hearst to swing his influence FDR’s way; FDR was later to appoint Kennedy the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission.)

“The advice of Hearst,” who had so vigorously and successfully supported Garner in the California primary, “apparently only reinforced a decision already reached by Garner,” Posner writes. Garner wanted a Democratic win in November and thought FDR had won enough support from the convention to deserve the chance at the race. Garner released his delegates, which triggered a series of internal votes in the California and Texas delegations; the two groups needed to determine whether the states, voting as blocs, would go for Roosevelt. After some debate, each decided to do so. In Texas’ case, the vote was a close one: 54 to 51.

William McAdoo, who was instrumental in swaying California to Roosevelt, declared the California delegation’s switch to the convention: “California came here to nominate a President of the United States. She did not come here to deadlock this convention or to engage in another disastrous contest like that of 1924.” In the end, FDR was nominated by a large margin of 945 to 190 ½ votes. (At that time, some delegates only had half a vote.)

Herb Snitzer/Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images

Roosevelt himself flew to Chicago to accept the nomination, a break with tradition. (This, writes William E. Leuchtenburg, was politically necessary: Roosevelt needed to demonstrate that he was “robust, strong, and energetic.”) He began his acceptance speech by acknowledging the unique circumstances:

The appearance before a National Convention of its nominee for President, to be formally notified of his selection, is unprecedented and unusual, but these are unprecedented and unusual times. I have started out on the tasks that lie ahead by breaking the absurd traditions that the candidate should remain in professed ignorance of what has happened for weeks until he is formally notified of that event…My friends, may this be the symbol of my intention to be honest and to avoid all hypocrisy or sham…Let is also be symbolic that in so doing I broke traditions. Let it be from now on the task of our Party to break foolish traditions.

Decrying the “leak-through” or “sift-through” theory of prosperity, Roosevelt declared “That theory belongs to the party of Toryism, and I had hoped that most of the Tories left this country in 1776.” Touching on aid to farmers and homeowners, the creation of public works programs, and the reconstruction of tariffs, FDR proclaimed: “We must lay hold of the fact that economic laws are not made by nature. They are made by human beings.”

The victorious and forward-looking rhetoric of the speech—so resonant to us now, in light of the New Deal and FDR’s long presidency—didn’t do much to leave onlookers confident of FDR’s chances in the general election. On July 2, Mencken reported: “The great combat is ending this afternoon in the classical Democratic manner. That is to say, the victors are full of uneasiness and the vanquished are full of bile.”

Here was a great party convention, after almost a week of cruel labor, nominating the weakest candidate before it. How many of the delegates were honestly for him I don’t know, but it certainly it could not have been more than a third. He was not only a man of relatively small experience and achievement in national affairs; he was also one whose competence was plainly in doubt, and whose good faith was far from clear. His only really valuable asset was his name, and even that was associated with the triumphs and glories of the common enemy. To add to the unpleasantness there was grave uneasiness about his physical capacity for the job they were trusting to him.

Every man has a right to life; and this means that he has also a right to make a comfortable living. He may by sloth or crime decline to exercise that right; but it may not be denied him. We have no actual famine or death; our industrial and agricultural mechanism can produce enough and to spare. Our government, formal and informal, political and economic, owes to every one an avenue to possess himself of a portion of that plenty sufficient for his needs, through his own work.

In the general election, Roosevelt was vague about specific policies, preferring simply to toe the line and let voters choose him as an alternative to the wildly unpopular Hoover. There was one exception: a speech in San Francisco in which he “hinted at the shape of the New Deal to come,” calling for a new era in which government would actively assure individual citizens’ welfare.

Greatly helped by the anger and worry that was epidemic in the electorate, Roosevelt was able to put the divisiveness of the primary season behind him and win by a landslide in November. Though his battles with his own party were hardly over, he was about to leave the “Feather Duster” image far behind.