The year since Ferguson has been full of echoes of the midcentury civil rights movement. The Montgomery Bus Boycott started three months after the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till; Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson served as a catalyst for Black Lives Matter activists. Network television’s widespread coverage of the civil rights movement of the 1960s mobilized national interest in the struggle against the racist institutions of the South, shocking white viewers with footage from Birmingham and Selma; in 2014 and 2015, the proliferation of smartphones, dashcams, and body cameras has yielded footage of encounters with police that has won national attention for what previously might have been overlooked stories of police brutality.

Parallels like these are striking, but how much do they help us understand the roots and direction of today’s activism? I contacted a group of historians of the civil rights movement to find out whether they too see a resemblance between the past and present—and whether those resemblances suggest we’re at the dawn of a new civil rights era.

The answer to these questions, it turns out, depends a lot on what you mean when you say civil rights era. Since the publication of an influential book by Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard in 2003 and a much-cited article by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall in 2005, historians have argued over the parameters of civil rights history. In popular memory, the civil rights movement stretched roughly from the bus boycotts in the mid-1950s to the assassination of Martin Luther King, in 1968. But some historians argue that it in fact began earlier and lasted longer than we usually think, running roughly from the 1930s through 1980. (Still others contend that the movement stretches all the way back to late-19th– and early-20th–century struggles against lynching and Jim Crow, or even 18th- and 19th-century slave revolts and resistance.) The historians I talked to also stressed that it’s important not to define civil rights activism too narrowly: It would be a mistake to consider only the boycotts and marches that have come to symbolize the midcentury movement. The activism of the “long movement,” they say, should be remembered as tactically diverse: Not everyone believed in nonviolent protest, and armed groups worked alongside nonviolent activists, even before the founding of the Black Panthers in 1966. The “long movement” was also more nationally dispersed—there were local actions in the North and West, as well as the South—than we usually remember.

This is very much still an active debate, but when I asked historians if the protests of the present remind them of protests of the past, they answered with this more complex, evolving portrait of the civil rights movement in mind. Many of them welcomed the question not only because they do believe that history informs our understanding of what’s happening today, but also because they hope that the public’s thirst for historical context might occasion a reconsideration of a civil rights movement whose popular history has become reverent hagiography. This is a moment, they said, to reassess who its leaders were; what issues it addressed; what tactics it used; and the length and breadth of its trajectory.

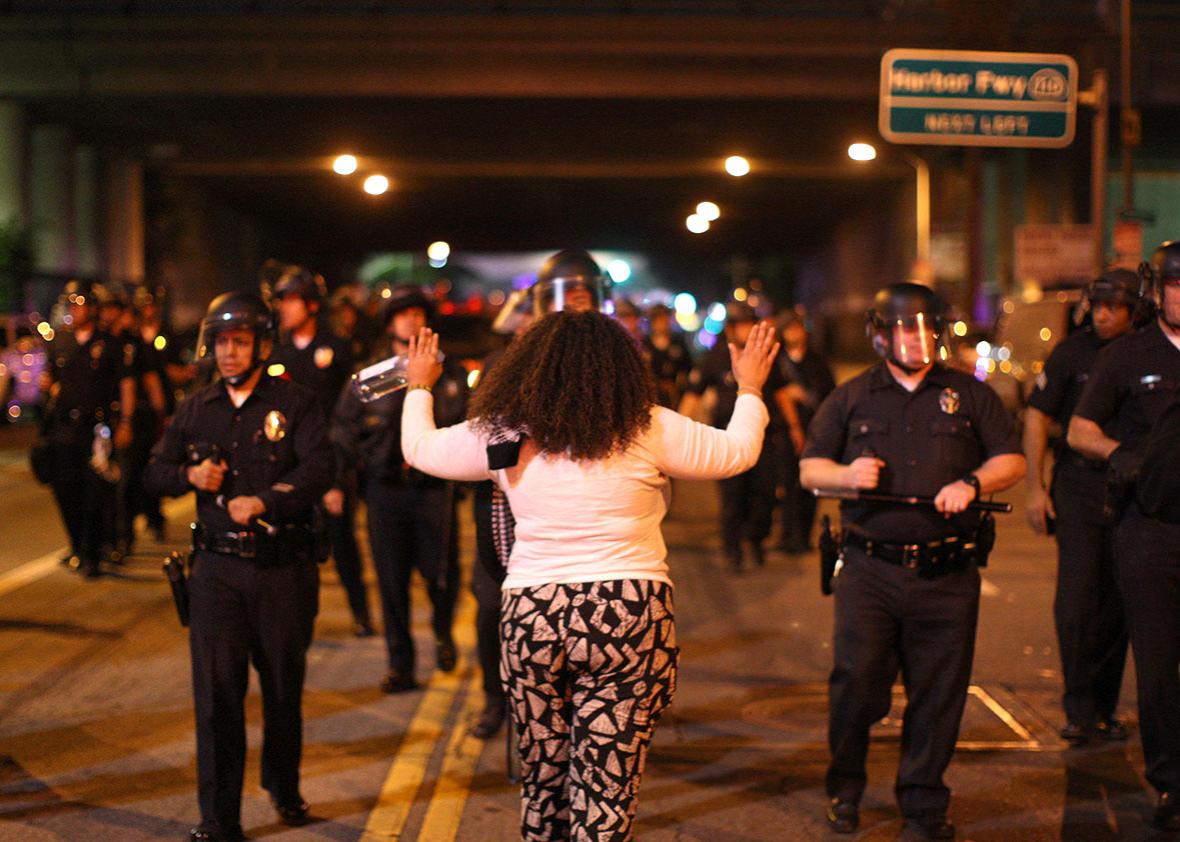

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Let’s start, though, with the period we’ve traditionally thought of as the civil rights era, stretching from the late 1950s to the mid-to-late 1960s. The historians I spoke with pointed out significant similarities between this time and the new activism of our day that haven’t received much notice. First: the youth of the movements’ leaders. Martin Luther King, Jr. was 26 at the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and many civil rights activists of that period, like the members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, were in college. Stefan Bradley, a historian at St. Louis University who has written about black student activism of the late 1960s and teaches present-day student activists, said in an email to me “The youth made the struggle work back then, and the youth are the driving force of the struggle now.”

The midcentury activists may look admirably precocious in hindsight, but at the time they seemed dangerous. Theoharis, a professor of political science at Brooklyn College, pointed to the 1951 high school strike led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns, which prompted the lawsuit that was reviewed along with four other cases in Brown v. Board. “If we think about the demonstrations in Birmingham in the spring of 1963, it’s young people; if you think about high school walkouts in the late 1960s from L.A. to New York; if you think about things like the Young Lords party here in New York City … we’re talking about very young people,” Theoharis added in a conversation over the phone. “That made our society nervous 50–60 years ago, and it makes our society nervous today.”

While segregation and disenfranchisement are often understood as the primary targets of the ’50s- and ’60s-era civil rights protesters, historians note that policing and criminal justice—the animating issues in our own time—were concerns for those activists as well. Brian Goldstein, an urban historian at the University of New Mexico, pointed to the “Harlem Riot” of 1943, which occurred when a black soldier attempted to stop a white policeman from arresting a black woman, after which the policeman shot him. During the iconic civil rights years, the way the movement was policed was a serious issue, as Kevin Kruse, a historian at Princeton, wrote in an email:

The abuse of power by local authorities was a constant theme in the civil rights movement, most notably in Birmingham (where Bull Connor not only deployed firehoses and German shepherds against protestors, but in echoes of Ferguson PD’s militarization, drove around town in a white military assault vehicle) and Selma (where Sheriff Jim Clark wore a military helmet, an Eisenhower style army jacket and a little lapel pin that said NEVER!).

Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people” was No. 7 on the Black Panther Party’s 10-point declaration of its program, and deaths of black people at the hands of police in California served as catalyzing events for Panther actions in the area. Panthers also confronted law enforcement directly, “policing the police” by patrolling Oakland neighborhoods with guns. Calls today for citizens to videotape police stops share some DNA with this kind of direct action.

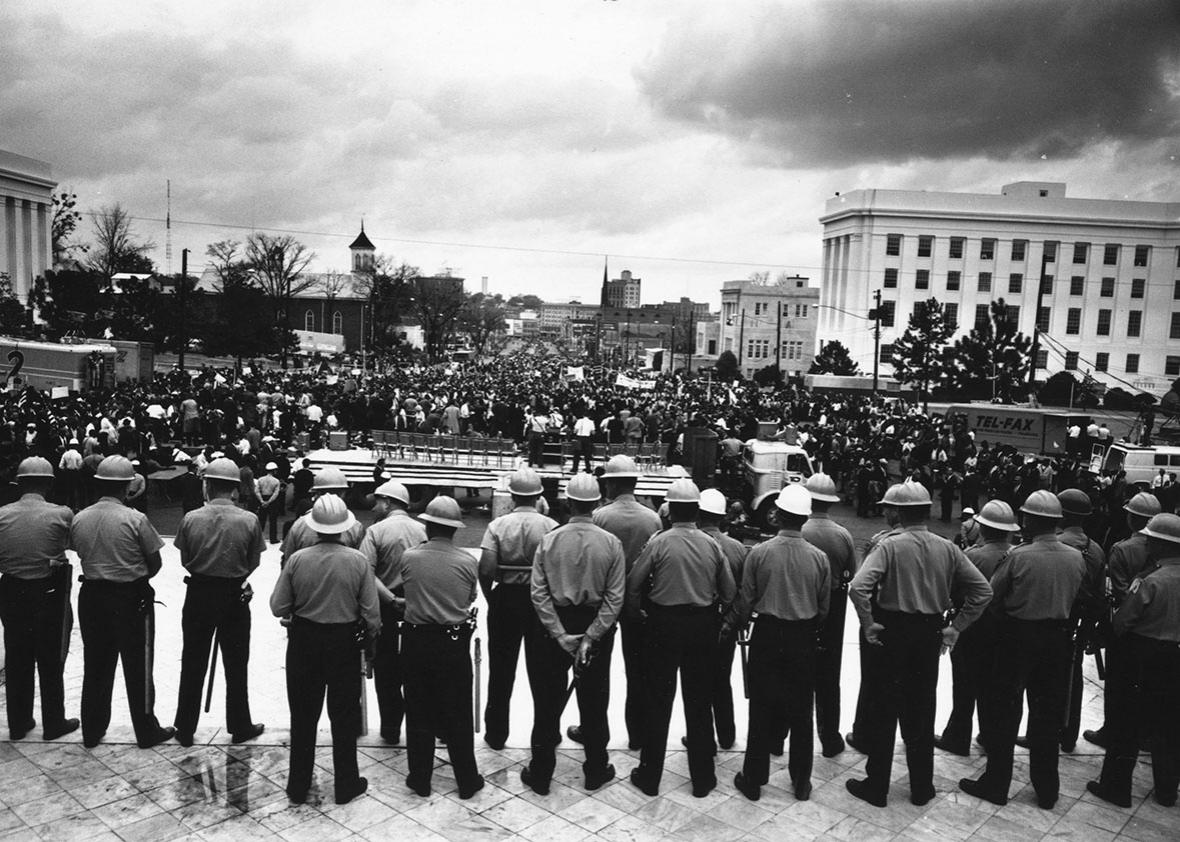

Photo by William Lovelace/Express/Getty Images

Many historians now consider the nonviolent activism of Martin Luther King and the more radical platforms of groups like the Panthers to be intertwined strands of the same movement. But the figure of King casts a particularly long shadow over today’s activism. The sainted caricature of the civil rights leader—Theoharis called the present-day memory of King a “Thanksgiving Day parade balloon,” one that ignores the leader’s persistence and radicalism—has been held up as an example to discipline contemporary activists, some of whom have been castigated for being insufficiently “calm” or “orderly.” Goldstein pointed out the “brave and confrontational stances and approaches” of some of today’s activists—like Bree Newsome, who scaled the flagpole at the South Carolina statehouse and removed the Confederate banner flying there—have come under fire from those who would prefer a less antagonistic approach. Even as some applaud actions like Newsome’s, Goldstein said, “I have also seen an uptick in hand-wringing responses to some of these events, from the position that confrontation is the ‘wrong’ way to engage or even some claiming that just as Black Power ended the Civil Rights Movement, this will end an incipient movement.”

Bradley added that this unfavorable comparison between nonviolent activists of the past and present-day Black Lives Matter protesters ignores the many phases of historical civil rights movements that weren’t particularly religious, nonviolent, or self-consciously “respectable”: “By the end of the 1960s, many young people were rejecting the ideas of respectability and messianic leadership that largely black middle class clergy espoused for those in the movement.”

Holding today’s activists up to King’s standard also reinforces the misconception that King was the solitary leader of the midcentury movement. Observers of Black Lives Matter have bemoaned the lack of a figure to play the role of King; in January, for example, Oprah Winfrey told People magazine, in an interview pegged to the release of the movie Selma, that she thought the new movement lacked leadership. University of Illinois at Chicago historian Barbara Ransby replied in Colorlines that Winfrey and others looking to name the “new Martin Luther King” forget that King was hardly the only civil rights leader, nor were his methods the only ones successfully wielded to effect change.

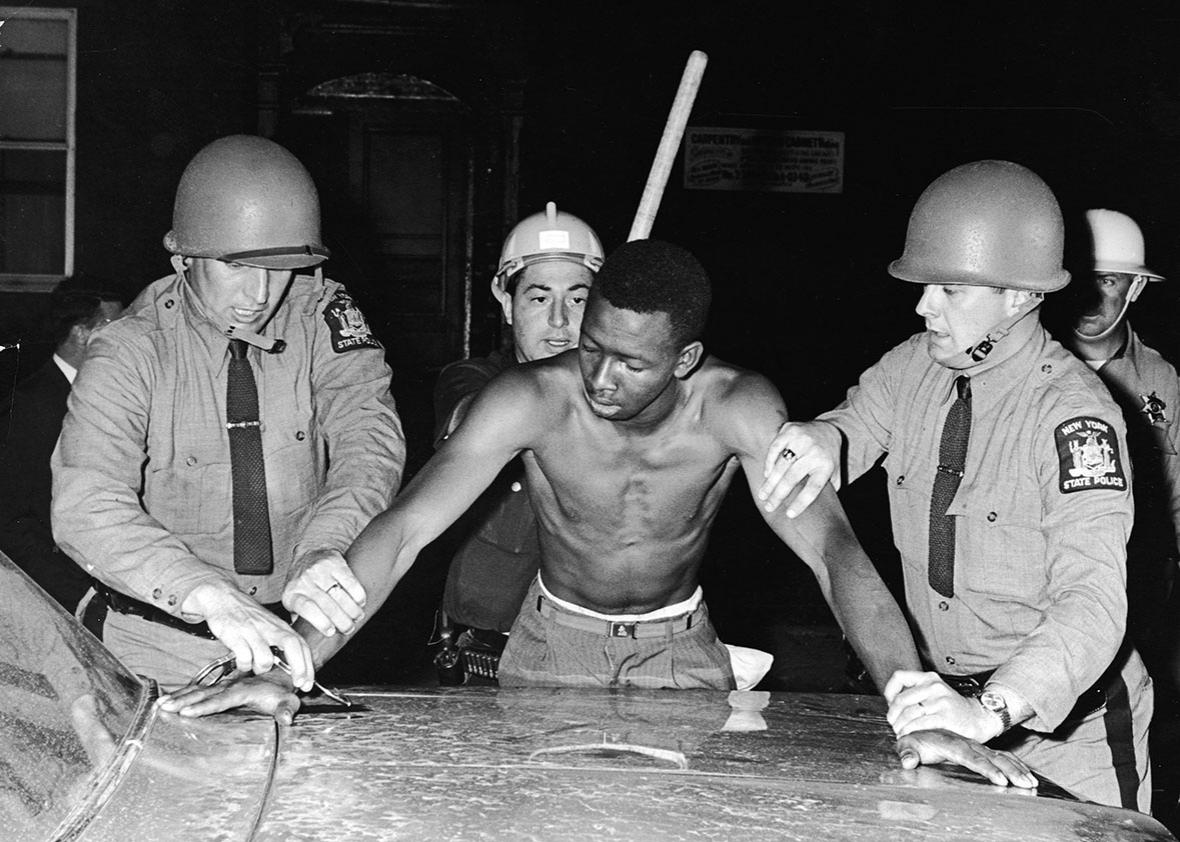

Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images

Ransby has written extensively on the midcentury activist Ella Baker, who worked with the NAACP, SNCC, and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Baker famously said that “strong people don’t need strong leaders,” but Ransby writes that the activist wasn’t against leadership, per se. Rather, she favored a distributed structure that would empower many people, instead of relying on a few charismatic figureheads. In other words, Baker envisioned the kind of movement that Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors (who is a director at the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights) has called “leader-full” rather than “leaderless.” Ransby points out that in the 1960s and 1970s, the SNCC and the Black Panther Party both pursued this model as well, looking to create strong groups of linked activists who operated from consensus.

The prominence of women and queer activists in the Black Lives Matter movement—a contrast with the largely male-dominated leadership we tend to imagine when we think of the midcentury movement—is an evolution that many historians I contacted noted, and applauded. They also suggested that the pre-eminence of women has contributed to the perception that the movement “has no leader.” “We have a lot of leaders,” one of Cullors’ co-founders, Alicia Garza, told the Guardian last month, “just not where you might be looking for them. If you’re only looking for the straight black man who is a preacher, you’re not going to find it.”

“It isn’t a coincidence that a movement that brings together the talents of black women—many of them queer—for the purpose of liberation is considered leaderless, since black women have so often been rendered invisible,” Marcia Chatelain, a historian at Georgetown, said in an interview with Dissent. “The most damaging impact of the sanitized and oversimplified version of the civil rights story is that it has convinced many people that single, charismatic male leaders are a prerequisite for social movements.”

* * *

One of the biggest problems with making comparisons between post-Ferguson activism and the midcentury movement is that it encourages us to skip over the 50 intervening years—as if no civil rights struggle, or progress, was made after the tumult of the 1960s. “In the popular imagination, King was assassinated in 1968, and maybe some people remember the Black Panthers or something, but after that, in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, it’s a blur in terms of civil rights, a feeling that nothing happened,” Jason Sokol, a historian at the University of New Hampshire who has written about the evolution of racial politics in the North over the past half-century, said in a phone interview. Yet struggles against segregation in housing and in schools continued. “Something like busing,” Sokol said, “really forced changes in [white Americans’] lives, not just in the South but across the country. I think a lot of whites were opposed to that in the way that they weren’t opposed to the opening of public accommodations in the South or voting rights for African-Americans.” For black parents living in a city like Boston, fighting to afford their children access to better schools in the 1970s, the civil rights movement was far from over.

Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images

In the years after the signing of the Voting Rights Act, black Americans made strides in representation in politics and in many professions. Bradley argues that this, too, should be considered part of the civil rights movement: “Those black people who took advantage of opportunities that affirmative action created worked to open previously closed doors to other black people. This occurred in governmental and private work places, and in many ways the everyday struggle of those workers helped to improve the culture of those spaces.” Students with new access to schooling in previously predominately white colleges, Bradley argued, “had to not only achieve scholastically, but they had to be soldiers in culture wars,” helping colleges integrate culturally while pursuing their own studies. Student-led efforts to force divestment in apartheid-era regimes in Africa in the 1980s, for example, could be considered an offshoot of the concerns of earlier civil rights activism. Looking for the roots of today’s activism only in the black-and-white footage of the “Eyes on the Prize” era, and not in these more recent efforts, creates gaps in our historical understanding.

Finally, there’s a historical irony that emerged from my search for the roots of Black Lives Matter. Much of the institutional racism that BLM is fighting can be traced to the passage of the Rockefeller drug laws in the early 1970s, and the tremendous growth of prisons and the increased stringency of policing in the intervening decades. And what prompted this turn toward heavy-handed law enforcement and mass incarceration? In a lecture reprinted in Jacobin, Rutgers historian Donna Murch connects these developments directly to the more radical black activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s: “Paramount to this history is the state response to the popular mobilizations of the postwar era and the criminalization of exactly the kinds of youth who participated in the popular upheavals of the 1960s urban rebellions and Black Power movement. It is in this moment of reaction that the seeds of contemporary police militarization were sown.” In other words, today’s activism can be seen as both an attempt to carry on with the goals of last century’s long civil rights movement, and a new struggle to overcome the forces that have arrayed, over the last 50 years, to curtail its progress.