In the days since Dylann Roof allegedly entered the Emanuel A.M.E. church in Charleston, South Carolina and killed nine people, many have called for the removal of the Confederate flag from the state house grounds in Columbia, among them the state’s governor, Nikki Haley. In a turn of events that few would have predicted, the calls have expanded beyond South Carolina. Alabama and Mississippi have also reconsidered their relationship to the flag, and many retailers have said that they will no longer carry Confederate flag merchandise. This rapid response, however, has led supporters of the flag to gather together in rallies. Their message has been that the flag stands for history, not oppression. “This is not a flag of hate. It’s a flag of heritage, and we have a right to our heritage,” Leland Browder of Greenville, South Carolina told the New York Daily News. “And, you know, I’m from the South and proud of the South and, you know, proud of this flag.”

The notion that the flag is a symbol of Southern heritage and nothing more is an ahistorical one. From the moment it was designed it was intended to convey the South’s reliance on the institution of slavery. When it has been revived by later generations, they, too, have imbued it with meaning. But it has always been a symbol of white power and racial oppression.

The flag was originally intended to symbolize the racial oppression central to the Confederacy. William Thompson, the designer of the official second Confederate flag (the “stainless banner” as it is often called), which featured the battle flag in the upper corner of an otherwise white field, said: “As a national emblem, it is significant of our higher cause, the cause of a superior race, and a higher civilization contending against ignorance, infidelity, and barbarism.” The editor of the Savannah, Georgia Morning News was pleased with the new design, noting, “As a people, we are fighting to maintain the heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored races.”

This symbolic association did not end with the South’s loss in the Civil War. If anything, it only intensified during Reconstruction, as Southern elites resented the political power afforded blacks through the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. During this period, the flag was rarely if ever seen in public settings. Northern politicians and supporters of Reconstruction saw the Confederate flag as a flag of treason.

With the fall of Reconstruction, however, the “southern cross” made a strong comeback, accompanied by a reassertion of white political power and belief in the “heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man.” The return of white political power also meant that Lost Cause ideology could be widely disseminated. The Lost Cause was an interpretation of history that argued that the Civil War was not fought over slavery but over states’ rights; that slaves had been happy and loyal; and that all the men who fought for the South were men of honor, none more so than Robert E. Lee.

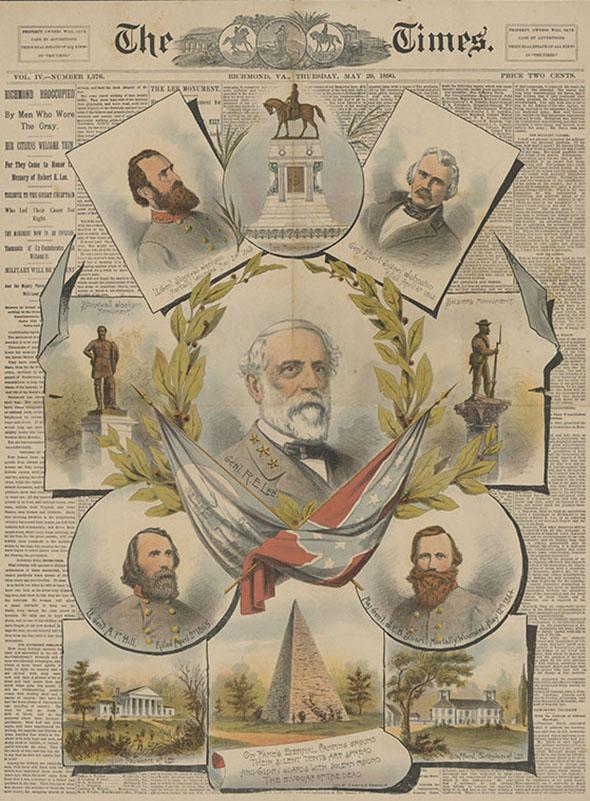

We can see the rise of Lost Cause orthodoxy, and the return of Confederate symbols, in events like the 1890 unveiling of the Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Confederacy. Now that the political power of those who supported Reconstruction had been rolled back, the white elite in the city planned a three-day event to coincide with the unveiling of the monument and planned the largest reunion of Confederate veterans to date. It featured dinners, banquets, parades, speeches, published biographies, and fireworks. According to newspaper accounts, there were more than 140,000 spectators. The parade was so long it took two hours to pass; it was headed by former Confederate generals on horseback and 20,000 uniformed former Confederate soldiers. The Richmond Times proudly declared: “Richmond Reoccupied by Men Who Wore the Gray.”

Courtesy of Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

Confederate flags, Confederate veterans, Confederate uniforms, and Confederate marching songs were everywhere. Such a bold and lavish display of the symbols of the Confederate States was noticed outside the South. Kansas Sen. John J. Ingalls, speaking at Gettysburg only a few days later, worried about the return of the “rebel colors.” Well aware of the extensive publications dedicated to promoting “Lost Cause” ideology and particularly disturbed by the attempt to rewrite the history of the Civil War in an effort to omit slavery, he reminded his listeners that slavery was the key to understanding the conflict. “Millions of human beings were held in slavery, cruel, monstrous, inconceivable in its conditions of humiliation, dishonor and degradation; … Eleven states seceded, or attempted to secede from the Union, to make this system of slavery, the corner-stone of another social and political fabric, and carnage reigned on a thousand battle fields.” National newspapers were also stunned by the respect shown the “flag of treason,” and when Southerners “put up that ensign of treason—the stars and bars—and make it a god to display, and to worship, we, as an American citizen, offer our solemn protest.”

Black Richmonders understood what the return of Confederate imagery meant. The local black newspaper, the Richmond Planet, published a column titled “What it means.” It reported of the festivities: “No flags of the Union ornamented the procession. Only the stars and bars could be seen, the ‘rebel yell,’ under the flag of secession which waved proudly after twenty-five years rent the air.” The editor predicted that this resurgence of Confederate ideology would only result in “a legacy of treason and blood,” and noted that “It serves to reopen the wound of war and cause to drift apart the two sections … [it] forges heavier chains with which to be bound.”

Photo by Zack Frank/Shutterstock

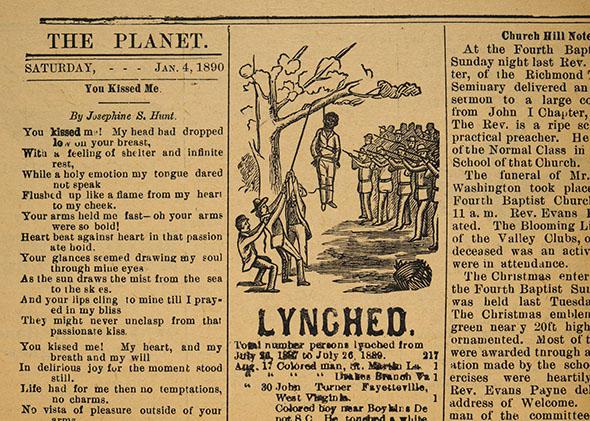

Blacks who had lived through slavery were all too familiar with the violence that held up the institution of slavery. Former slaves who recalled the regular militia patrols that were part of the machinery of slave owner control would have thought these extensive military parades a familiar site. Since the end of the war, there had been a rise in racially motivated lynchings, another reminder of white power. For many blacks in the South, emancipation had done little to change the omnipresent threat of violence in their lives. In Richmond, the Planet regularly carried word of the most recent incidents of racial violence. Just months before the unveiling of the Lee Monument, the paper depicted such a killing with armed men standing guard. When 20,000 Confederate veterans marched through the streets of Richmond, it wasn’t difficult to make a connection between massive military parades and white power.

Courtesy of Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

In 1890, black rights in Virginia were still protected by law, but not for much longer. This reappearance of Confederate symbolism coincided with resurgent white political power. Just weeks after the Confederate reunion, the editor of the Planet noted that many black residents had their names removed from voter rolls and that they had been intimidated in other ways as well. “We have been vilified, abused, maltreated and ostracized, whipped and butchered,” he reported. By 1902, Virginia had a new state constitution with provisions that successfully disenfranchised most blacks and set the Jim Crow laws of segregation firmly in place. The laws would remain in place until the state ratified a new constitution in 1971. A black man who watched “the mammoth parade of the ex-Confederates,” with all of its “rebel flags” sighed, “The Southern white folks is on top—the Southern white folks is on top!” No more needed to be said.

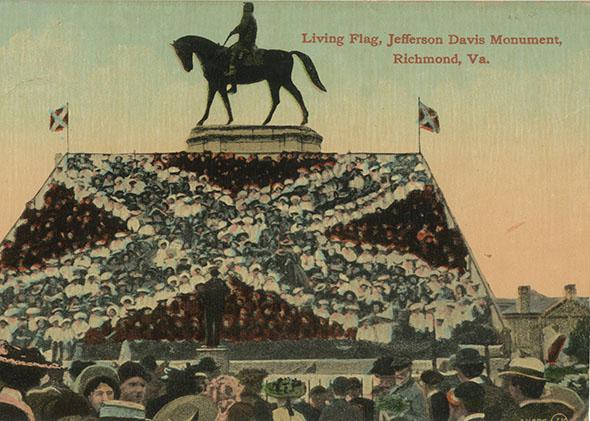

By the 20th century, white voters throughout the South had pulled power back from the Republicans and the supporters of Reconstruction. Jim Crow laws had instituted government-sanctioned segregation, and the displays of white political power coupled with Confederate symbolism continued. Confederate reunions were held annually in Richmond until 1932 and were a common practice in other cities throughout the South. Each year, mounted cavalry officers, soldiers, and parades filled the cities with the Southern cross. In Richmond, these ceremonies grew grander and bolder, as shown by the “living flag” re-creation below the Lee Monument in 1907. According to the back of the postcard pictured below, the event was staged by 600 costumed school children who dressed in the colors of the flag and stood in the form of the Southern cross. They sang “Dixie and other Southern airs.” In nearly every town, one or more Confederate memorials were raised. Equestrian statues, soaring columns, and standing soldiers created a landscape of steady reminders.

Courtesy of Maurie McInnis’

As the Confederate veterans died off in the 1920s, reunions diminished in their size, scale, and spectacle and the flag and other Confederate symbols became less frequently seen. To many, it might have appeared as if finally the Southern cross would leave the public sphere and fly only in museums, a relic of history. But it was not to be. It returned in 1948. This time it accompanied the rise of the segregationist “Dixiecrat” party. Led by Strom Thurmond, there is no doubt that this party, like the Confederate States of America, was a white supremacist organization. In 1948, Thurmond avowed, “all the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement.”

When Dylann Roof photographed himself holding the Confederate battle flag and a handgun, he did so because the flag held particular symbolism to him, symbolism that he believed others reading his website, “The Last Rhodesian,” would easily understand. According to Roof’s manifesto, the Southern cross symbolized a deep and abiding racial hatred. For him, it was clearly a symbol of white supremacy. That was its attraction.

There are many today who see it instead as a symbol of family, history, region, or even a statement in favor of small government. But the flag has always been first and foremost a symbol of white supremacy: It was designed as such, and has functioned as such whenever it has returned to the public square. For more than 150 years, it has been used to communicate a history of racial oppression and to intimidate in the present. Those who want to argue for the flag’s “heritage” need to understand the full, complicated, and ugly history behind the symbol. There is no way that it can be cleansed of its historical meanings. It is forever stained with the blood of the millions who were oppressed by slavery, the millions more who were oppressed by the racial segregation of the 20th century, and now the blood of those slain in Charleston in our own century.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Charleston shooting.