Excerpted from Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition by Nisid Hajari, out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Throughout August 1947, as Hindus and Muslims and Sikhs engaged in one of the most terrible slaughters of the 20th century in next-door Punjab province, lights continued to blaze from New Delhi’s ivory-white Imperial Hotel. On weekends, diners packed the tables in the Grill Room overlooking the lawns, while Indian socialites dripping with gold and jewels filled the dance floor well past midnight. To many of the city’s well-to-do, the bloodshed that had erupted upon the birth of modern India and Pakistan still felt unreal. The Indian women in particular seemed to be “on heat,” one British journalist noted hungrily. “The aphrodisiac was independence.”

No band played on Saturday, Sept. 6, however. A curfew had emptied the dining room. Anyone standing on the hotel’s veranda would have been bathed in a different light—a rose-colored glow that filled the horizon to the north. The Muslim neighborhoods of Old Delhi were on fire.

When they imagine the terrible riots that accompanied the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent, most people are picturing the bloodshed in the Punjab. On Aug. 15, the new border had split the province in two, leaving millions of Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs in what was now Pakistan, and at least as many Punjabi Muslims in India.

Gangs of killers roamed the border districts, slaughtering minorities or driving them across the frontier. Huge, miles-long caravans of refugees took to the dusty roads in terror. They left grim reminders of their passage—trees stripped of bark, which they peeled off in great chunks to use as fuel; dead and dying bullocks, cattle, and sheep; and thousands upon thousands of corpses lying alongside the road or buried shallowly. Vultures feasted so extravagantly that they could no longer fly.

As awful as the carnage was, though, it was for much of August concentrated in the Punjab. The combatants were mostly peasants, armed with crude weapons. If the two new governments had managed to quell the mayhem quickly, they might in time have found scope to cooperate on issues ranging from economic development to foreign policy. Instead, the infant India and Pakistan would soon be drawn into a rivalry that’s lasted almost 70 years and has cast a nuclear shadow over the subcontinent.

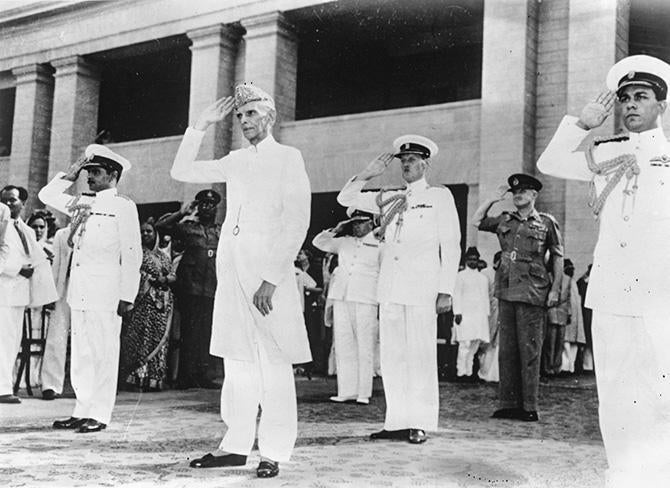

A few short days in Delhi at the beginning of September 1947 helped to tilt the scales. Most train services across the new border had been suspended because of the spiraling massacres, stranding thousands of Muslim civil servants destined for Pakistan in the Indian capital. Desperately short of staff, the Pakistani government was already struggling to cope with hundreds of thousands of traumatized refugees and a stalled economy. Pakistan’s prickly founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, suspected the Indians of deliberately seeking to sabotage his fragile state.

Photo by Keystone/Getty Images

His fears weren’t entirely unfounded. For several days running, according to some eyewitness reports, small groups of Sikh and Hindu militants had been roving the broad, manicured avenues of New Delhi, defying the curfew. Some appear to have been marking out the rooms in government dormitories occupied by Muslim clerks and peons, as well as the houses and bungalows where Muslims lived or worked as servants. A British diplomat later reported seeing a lorry full of Sikhs pull up outside the home of the local chairman of British airline BOAC, which had agreed to transport Muslim officials to Pakistan by air until the trains resumed. “That’s the place,” one of the Sikhs confirmed, carefully noting down the address.

On the night of Sept. 6, sword-wielding gangs began working their way from target to target, dragging out and killing Muslims. The next morning mobs took to the streets all over the city. One descended on the military airfield at Palam, from where the BOAC charters were taking off; another blocked the runways at the civilian Willingdon Airfield as airline employees fled in terror. Muslims caught out in the open were stabbed and gutted, including five who were killed in front of New Delhi’s cathedral while worshippers celebrated Sunday Mass. Looters broke into Muslim shops in Connaught Place, the colonnaded arcade at the heart of the city. By 10 that night, Delhi hospitals were reporting three times as many Muslim as non-Muslim casualties.

Rushing to Connaught Place, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was appalled to see a contingent of police standing by idly as Hindu and Sikh rioters carried off ladies’ handbags, cosmetics, and wool scarves—even bottles of fountain-pen ink. Nehru grabbed a baton from one indifferent policeman and flailed away at the crowd himself. The prime minister would learn later that Delhi police had picked up rumors that “two well-known [Sikh] extremists from Amritsar” had organized refugees from the Punjab into makeshift killing squads. Plot or no, Delhi’s police appeared content to let the rioters go about their business unmolested.

Although they later tried to play down the extent of the chaos, Nehru and his deputy, the tough Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel (known as “Sardar,” or Chief), at least temporarily lost control of their own capital. Ministries sat empty because clerks and officials were too afraid to come to work. Buses, taxis, and horse-drawn tongas—usually driven by Muslims—stopped plying the roads. The phones went dead. Within 48 hours, hospital mortuaries had filled to capacity; dozens of bodies lay unclaimed on the streets for days. With food shipments rotting in abandoned trains, ration shops closed up. At one point the city had only two days’ stock of wheat in reserve.

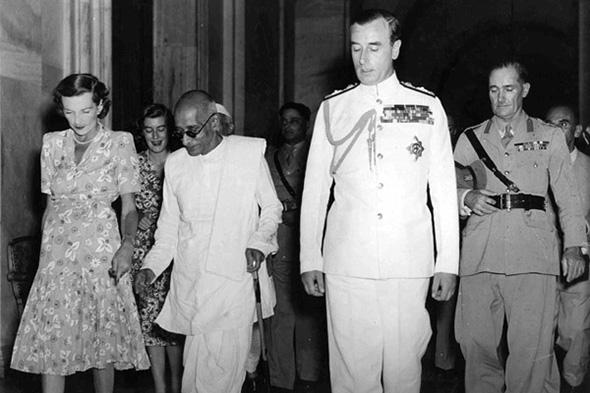

Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain’s last viceroy, had stayed on after independence to serve as India’s first governor-general. Many of his staff members had seen combat with him during World War II; even they were stunned by the whirlwind. “This is more hectic than at any time of the war,” Mountbatten’s chief of staff Lord Hastings Ismay wrote to his wife—a potent statement from a man who had lived through the Blitz. He advised her to cancel her plans to come out to see him: “There is a possibility—and most keen a possibility—that orderly Government may collapse.”

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Initially none of the Indian leaders doubted that Sikhs, who had played a central role in the Punjab violence, had spearheaded the Delhi attacks, too. More than 200,000 non-Muslim refugees from the Punjab had squeezed into the capital, and plenty of them thirsted for revenge. Patel called in local Sikh leaders and threatened to toss their followers into concentration camps if the violence did not cease. He also gave the army a “free hand” to go after Sikh troublemakers. Commanders ordered their troops to shoot rioters on sight. Though the military could not admit openly to targeting any particular community, Mountbatten joked grimly, “the object would have been achieved if in 48 hours’ time the local graves and concentration camps were occupied more fully by men with long beards than those without.”

Very quickly, however, Patel’s assessment of the threat changed. The problem was not just the Sikhs. Earlier police reports had also warned of a brewing Muslim uprising in the capital. Most of the city’s ammunition dealers were Muslim, as were most of its blacksmiths. The latter had supposedly converted their workshops to churn out bombs, mortars, and bullets. Patel had been worried enough about the threat to issue licenses to several new Hindu arms dealers in Delhi. He had “been giving arms liberally to non-Muslim applicants” for self-defense, he reassured a colleague.

Some Delhi Muslims were indeed armed. They fought back against the police as well as the Hindu and Sikh gangs; among reported gunshot victims on Sunday, non-Muslims actually outnumbered Muslims 45 to 20. Though evidence of any conspiracy is scant, quite a few Delhiites seemed to believe that the city’s Muslims posed as great a threat as the death squads, if not greater.

During the riots, officials trying to rescue Muslims often found the public reluctant to help. Owners of private cars and trucks removed key parts so that the authorities couldn’t requisition the vehicles. Volunteer drivers pretended to get lost or to develop engine trouble when asked to deliver aid to Muslim areas. (Eventually the government enlisted idealistic students to ride along and watch over them.) Even four days into the rioting, the U.S. military attaché witnessed Indian army troops standing by as Muslim women and children were clubbed to death at Delhi’s railway station.

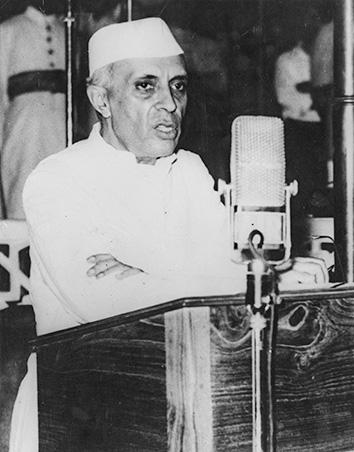

Photo by Keystone/Getty Images

Patel was more in tune with the popular mood than Nehru. While the principle that Hindus and Muslims should be able to live together remained central to Nehru’s vision for India, the Sardar was less sentimental. He did not trust that all of India’s Muslims, many of whom had until recently supported Jinnah, had switched loyalties. If they did not think of themselves as Indians, he believed, then they belonged in Pakistan.

Nehru would almost certainly have lost an open fight with his deputy. Horrified by the casualty reports, the prime minister tried to ban Sikhs from wearing their ceremonial knives, known as kirpans. Patel pushed back, saying the decree discriminated against the Sikh faith. “Murder is not to be justified in the name of religion,” Nehru protested. Yet after a “violent disagreement” between the two men, the Sardar triumphed. Sikhs regained the right to carry their daggers after a 48-hour pause.

Nehru seemed to believe he had a better chance of quelling the unrest single-handedly than by working through his own administration. He went “on the prowl whenever he could escape from the [Cabinet] table, and took appalling personal risks,” Ismay recalled. Nehru would angrily face down mobs himself, rushing from trouble spot to trouble spot. A veritable tent city, filled with Muslim refugees, sprouted on the lawns of his York Road bungalow.

One night a Muslim friend named Badruddin Tyabji showed up at Nehru’s door to alert him to an especially troubled area—the Minto Bridge, which Muslims fleeing their Old Delhi neighborhoods had to cross to reach the safety of refugee camps in New Delhi. Each night, Tyabji said, gangs of Sikhs and Hindus lurked nearby and sprung upon the defenseless Muslims as they trudged past.

Nehru immediately bolted from his seat and dashed upstairs. He returned a few minutes later holding a dusty, ungainly revolver. The gun had once belonged to his father, Motilal, and hadn’t been fired in years. He had a plan, he told Tyabji. They would don soiled and torn kurtas and drive up to Minto Bridge themselves that night. Disguised as refugees, they’d cross the bridge, and when the thugs tried to waylay them, “We would shoot them down!” The stunned Tyabji was able to persuade the leader of the world’s second-biggest nation “only with great difficulty” that “some less hazardous and more effective method for putting an end to this kind of crime should not be too difficult to devise.” Mountbatten feared Nehru’s impulsiveness would get him killed and assigned soldiers to watch over him.

Nehru’s individual heroics evoked great admiration in men like Ismay and Mountbatten. But they did little for Delhi’s Muslims. After the initial wave of attacks, thousands had fled their homes. Authorities almost immediately started evacuating the rest, claiming they could not guarantee the safety of residents if they remained where they were.

Muslims were dumped in guarded sites by the truckload—places which it would be generous to describe as refugee camps. Within a week, more than 50,000 were crammed into the Purana Qila, a ruined fort. They huddled pitifully on the muddy ground with no lights, no latrines, and hardly any water or food. The Pakistan government flew in shipments of cooked rice and chapatis all the way from Lahore to feed them.

Photo by AP

Ismay melodramatically compared the scene at the Purana Qila to “Belsen—without the gas chambers.” Dignified Muslim professors and lawyers were squashed next to cooks and mechanics, longtime Gandhians next to stranded, would-be Pakistan bureaucrats. Wounded and sick moaned without medical attention; babies were born in the open. Armed Sikhs patrolled the one choked entrance, taking down the license plate numbers of Europeans driving in to deliver food and supplies to their friends and former servants.

With the help of Gurkha and South Indian troops—who were less vulnerable to the sectarian passions roiling their northern counterparts—authorities managed to control the worst of the violence within a week. Volunteers began to clean up the streets, and ration shops reopened. Nehru asked the governors of other Indian provinces to take in tens of thousands of Punjab refugees, to get them out of the capital.

But the riots fatally undermined any trust Pakistani leaders may have had in their Indian counterparts. Nehru’s estimate that 1,000 victims had died in the rioting was generally considered “ridiculous,” according to U.S. Ambassador Henry Grady. He figured the true toll to be at least five times higher; others said 20 times.

Photo by Margaret Bourke-White/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

At the height of the violence, Jinnah was inundated with hysterical reports from the Pakistani ambassador in Delhi, Zakir Hussain. Hundreds of Muslim refugees had carpeted the grounds of his house, Hussain reported, and the embassy’s food supplies were running out. He described the Indian government as either intent upon eliminating the capital’s Muslim population or indifferent to their fate. Army troops were openly gunning down innocent Muslims. In one particularly florid cable Hussain warned, “The entire Muslim population of India is facing total extermination.”

A conviction was taking hold among Jinnah and his lieutenants that India had launched an “undeclared war” on the weaker Pakistan. The Indian leaders seemed incapable of transferring Pakistan government servants to the new capital Karachi, or of protecting them in their Delhi homes. Cargo trains full of equipment and supplies meant for Pakistan were being derailed and torched in the Punjab. At least some members of the Indian Cabinet appeared to be winking at the Sikhs’ murderous activities. “It is obvious that their orders are not carried out,” one of Hussain’s cables said of the Indian leaders, “or at least different members of the government are following conflicting policies.”

In mid-September, Ismay spent three days in Karachi trying to convince Jinnah that the Indian government bore Pakistan nothing but goodwill. Jinnah was dismissive. He was convinced that Sikh and Hindu militia leaders had planned the violence in the Punjab as well as Delhi. Though intelligence had given some inkling of their plans over the summer, they had been allowed to walk free. With its vast resources and powerful military, Jinnah believed, India could even now have suppressed the Sikhs if only Nehru had had the necessary “will and guts.” Instead he could not even guarantee the safety of Muslims in his own capital.

Ismay returned to Delhi profoundly depressed. In a secret codicil to his report, meant for Mountbatten’s eyes only, he warned that Jinnah had begun speaking in dangerously warlike tones. In the very first hour of their talks the Pakistani leader had struck Ismay “as a man who had given up all hope of further cooperation with the Government of India.” All that had happened in the month since independence just “went to prove that they were determined to strangle Pakistan at birth,” Jinnah had told Ismay grimly. “There is nothing for it but to fight it out.”