In trying to understand the historical context behind the massacre of nine people attending a prayer meeting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, many people have pointed to the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, or the string of arsons directed at Southern black churches in the 1990s. But black Americans know that the history of white terror against us, and our churches, runs much deeper than that. We know this vicious attack is only the latest manifestation of an intense hatred of black Americans that is stitched throughout the entire fabric of the nation’s history. Black American places of worship have represented a threat to white supremacy’s various forces since they emerged among free black populations living in cities throughout the U.S. in the late 18th century.

Black churches have long provided physical and spiritual sanctuary from anti-black racism. In their sacred spaces, African Americans can worship and discuss political and personal matters as they wish, often free of white influence or surveillance.

Black churches tend not only to the spiritual and emotional well-being of their members, they address social and economic needs of the larger community by providing a range of services. Historically, churches provided instruction for enslaved and free blacks and often housed schools and benevolent organizations. Churches were a focal point for African American communities’ political organization and mobilization as well.

Throughout history black churches also served as a centralizing force of social justice. Churches aided the fight against slavery, and black congregations and individual members across the nation assisted men, women, and children escaping the horrors of slavery.

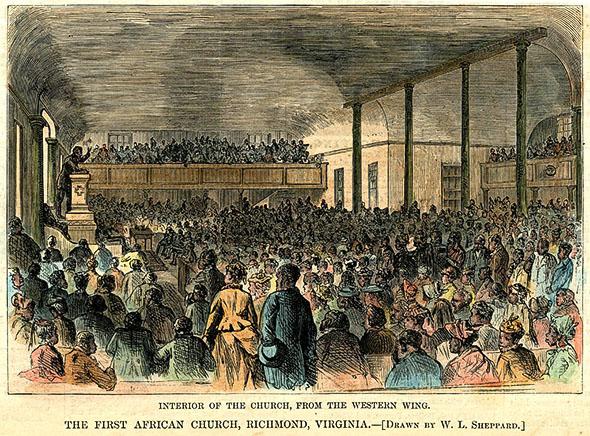

Before the Civil War, independent black churches met openly primarily in the North. Southern churches, like “Mother Emanuel,” often met in secret because white Southern lawmakers banned them out of fear that black churches would foment rebellion among enslaved people. After the war, many black Southerners withdrew from white churches and formed their own. Allowed to meet openly, Southern churches were the lifeblood of African Americans’ aggressive fight to make freedom real. For them this included everything from social and economic independence from whites to a degree of political power to protect their interests.

Churches shouldered a lot of the burden for educating and organizing freedpeople during Reconstruction. Many black political figures of the era had direct ties to the clergy. Legal fights against racial discrimination often grew out of churches whose members filed lawsuits to have the right to do everything from being buried where they wanted, to travel with first-class accommodations. Given the historic social and political power of black churches, it is no wonder they have come under literal fire, especially at the hands of individuals and organizations determined to maintain white supremacy. (For more on the political role of the black church, and the threat it’s posed to white supremacists, read Matthew J. Cressler’s essay in Slate.)

Many whites who were looking to preserve white social, economic, and political supremacy over blacks after the war typically used terror to achieve their objectives. White terrorists came from all levels of southern society. Some men struck political figures, and others vented their rage at laborers who rejected working conditions akin to slavery or were prospering under freedom.

White men attacked blacks individually and as members of armed gangs that terrorized communities across the South. Gangs typically raided African Americans’ homes in the middle of the night and held families hostage while they plundered, raped, tortured, and murdered captives. White supremacists maimed and killed hundreds of black people and drove many families from their homes and communities. They also attacked important black institutions like schools, businesses, and churches.

In South Carolina, White men burned and destroyed black churches during reigns of terror throughout the state. African Americans’ testimonies at the congressional hearings investigating the Ku Klux Klan in 1871 open a window into this history.

Benjamin Gore, a resident of Chester, was one of more than 200 African Americans who testified about these attacks before the committee. Gore told members of Congress that he witnessed a church burning in 1871 during a battle between whites and a black militia that was fighting back. He said he was standing on his doorstep when he “saw the fire commence kindling.” He testified that he then saw three white men on horseback, leaving the church and rejoining a larger group of men who redirected their assault toward the blacks defending their community.

In 1871 a gang of white men visited the Spartanburg County home of Alberry Bonner. They snatched him, dragged him outside, stripped him naked, and then whipped him. Bonner also testified that white men tore down his church as part of a larger attack on the community.

A deacon from Limestone named Doctor Huskie testified about a raid on his home in December 1870 and an attack on his brother. Huskie and his neighbors started sleeping outside to avoid being trapped in their homes in case the white men returned. His community’s church was burned down the following June.

White terrorists were not always satisfied with attacking places of worship; they also targeted church leaders. White men from Union County ordered Lewis Thompson to stop preaching in 1870–71. They even drew a picture with a coffin and Thompson’s name on it and placed it at a church near Goshen Hill where he was scheduled to preach. His brother, Dennis Rice, testified that Thompson still preached but congregants were so afraid of being attacked in the church that they “wouldn’t stay to hear him.” Thompson was undaunted and continued trying to spread the Gospel.

White men kidnapped Lewis Thompson on June 16, 1871, and murdered him. Thompson’s mutilated body was recovered from a local river shortly thereafter. Klansmen warned the family against burying his remains.

As violence like this continued, the federal government stepped in. Agents swarmed the South, infiltrated white terror groups, and issued thousands of indictments. In South Carolina, authorities declared martial law and conducted trials.

Thousands of Klansmen and their ilk fled, seeking sanctuary in communities that were hospitable to their mission. Even in cases where authorities tried perpetrators, finding witnesses to testify against them and juries that were willing to convict them was difficult. Only a few men served time for their crimes.

This violence was critical to the restoration of ex-Confederates and their allies to political power across the South. It continued throughout the Jim Crow period when black churches provided sanctuary from the brutal realities of segregation and racial terror and served as meeting centers for the fight against it.

A tradition of activism made church buildings, leaders, and members primary targets of white men who were determined to maintain segregation and deny blacks the right to vote. This is especially clear in the church bombings and burnings of the 1950s and 1960s. Because of the real and imagined threats black churches posed, they remained targets of white violence and hatred throughout the 20th century, with a spate of burnings and fire-bombings in the 1990s that triggered a 1996 congressional investigation.

When Dylann Roof, the alleged perpetrator of this week’s shooting, walked into the prayer meeting at Mother Emanuel, it is not clear that he knew was striking the site of Denmark Vesey’s 1822-planned revolt against slavery on its 193rd anniversary. But firsthand accounts of his heinous act, and his participation in white supremacist Internet forums, indicate that he entered the church with an intense hatred for black Americans.

Connecting the dots among Roof’s racism, his living in a state that continues to cloak itself in symbols of white supremacy and the Confederacy, and his decision to enter the Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney’s church and pray with congregants before opening fire and killing six women and three men is not difficult. In striking Mother Emanuel, with its tradition of preserving and promoting black solidarity, Roof aimed his gun at the very heart of African American communities in Charleston and around the country.

For some people, Roof’s killing of Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Depayne Doctor, Cynthia Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Daniel Simmons Sr., and Mira Thompson is an isolated incident. But for many black Americans, it is impossible to separate them from two centuries of white supremacist violence, from Walter Scott and other victims of police killings; Kalief Browder and the hundreds of thousands ensnared in the carceral state; and from the murder of Renisha McBride and girls and women like her.

Black people know the history of violent racism connecting the massacre to ships carrying African captives across the Atlantic to terror strikes after the Civil War, whether perpetrated by individuals or the state. Carrying this history in our bodies and souls, we see the connections because as a people facing yet another low point in U.S. history, we do not have the luxury of forgetting or ignoring them.

As we join Charleston in mourning, we know that Roof was not alone when he entered Mother Emanuel. He was standing on the shoulders of the white terrorists who came before him. Today black Americans are searching for ways to honor the lives of people taken so brutally. Our knowledge of the U.S.’s long history of racial terror and endless denials about it makes it hard to suppress our rage about how little has changed. Knowing that white terror is not outdated, the fact that authorities have decided to investigate the killings as a “hate crime” offers little comfort.