To this day, nobody knows the true fate of Capt. William Morgan. A failed businessman and citizen of generally low repute, Morgan was abducted from his home, in the town of Batavia, New York, in the early morning of Sept. 11, 1826. He soon found himself in a Canandaigua jail cell, about 50 miles away, imprisoned for a debt of $2.65. The whole ordeal was doubtless confusing to Morgan, a man best known for his drinking. It likely became even more confusing when a stranger paid his bail. But that man had no intention of setting him free. Morgan emerged from the jail only to be forced into a carriage, reportedly screaming out “murder” while he was being dragged away.

This is the last anyone ever saw of Morgan, about whom little else is certain. Some said that he was not really a military captain, while others claimed that he had earned that title in the War of 1812. Others asserted that both theories were technically true: That he fought the British in 1812 as a pirate seeking plunder and was granted a pardon for his misdeeds by the president after the war. What we do know is that whatever happened to him, trapped inside that northbound carriage and fearing for his life, Morgan never came back.

Over the next few years, the details of Morgan’s abduction would slowly come to light, setting off a political firestorm and giving rise to the first third party in American politics. Evidence suggested that Morgan’s abduction was carried out by members of a secret organization known as the Masons. Americans soon came to believe in the existence of a Masonic plot to overthrow society from within; the country’s very existence, many proclaimed, was now in jeopardy. What began as an obscure crime in upstate New York would spark one of the first episodes of political hysteria in American history, laying the foundation for a long line of political crusades to come.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

The story of Morgan’s disappearance begins in the summer of 1826, when a new era was dawning in the nation’s history. Fifty years after the Declaration of Independence, the last of America’s founding generation was dying off—a turning point highlighted by the deaths of both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the Fourth of July that year. What would become of America’s “great experiment” in democracy without the presence of the founders?

In upstate New York, then on the outer edges of America’s frontier, two men were occupied with a different question: how to secure personal fame and fortune. The first was David C. Miller, the publisher of Batavia’s Republican Advocate. Miller’s was an opposition paper, pitted against the policies of New York’s governor, DeWitt Clinton. Though he’d run the journal for more than a decade, he was still a struggling newspaperman searching for higher circulation. The second was William Morgan, who had moved his family restlessly throughout the countryside, working first as a brewer, now as a stoneworker, hauling his wife, Lucinda, and two young children from one failed venture to the next. Only two years earlier, Morgan had written of his desperation: “The darkness of my prospects robs my mind, and extreme misery my body.” The two men made an odd pair, but what they lacked in common background they shared in common circumstance—and now in common goals. Over that summer the two hatched a plan to expose to the world the inner workings of the secret society of Freemasons.

How, exactly, the two first came into contact is not known, but neither was held in high esteem by his community. According to one source, Miller was known to be a man “of irreligious character, great laxity of moral principle, and of intemperate habits”; much worse things were said about Morgan. Not surprisingly, both men harbored deep-seated animosity toward Freemasonry, which served as a symbol for the establishment class.

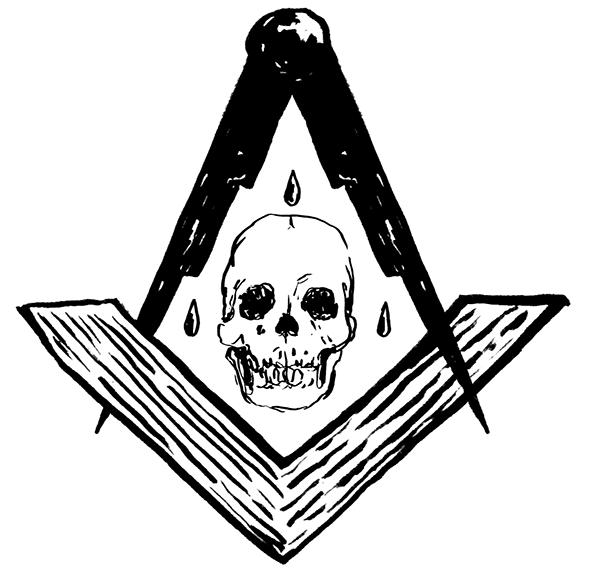

Freemasonry is thought to have originated in England and Scotland sometime in the 1500s as a trade organization made up of local stoneworkers, but it soon took on a philosophical air. The triumph of reason began to be a focal point of the organization, as did dedication to deism, or the Enlightenment belief that the existence of God is apparent through observation and study rather than miracles or revelation. Over the centuries, the fraternity of Masons would expand throughout the world, as would its ceremonies and rituals, which involved strange symbols and oaths—in addition to its more benign emphasis on civic-mindedness, religious tolerance, and communal learning. The group met in secret.

Masons were overwhelmingly men of middle- and upper-class status—doctors, lawyers, and businessmen—who had the time and leisure to join what amounted to a social club for the well-to-do. Many of the founding fathers had been Masons, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin—indeed, 13 of the 39 signers of the Constitution claimed membership in the fraternity. In the years between America’s founding and 1826, Masonry had only grown more powerful, especially in New York. Gov. DeWitt Clinton was not only a Mason but had also been the grand master of the Grand Lodge of New York and the highest-ranking Mason in the country. By one estimate, more than half of all publicly held offices in New York were occupied by Masons.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

Miller first hinted at some type of forthcoming revelation in an article published in the Advocate in August 1826. He had discovered the “strongest evidence of rottenness,” he wrote, evidence that compelled him and an unnamed collaborator, “to an act of justice to ourselves and to the public.” This bombshell was a book, to be compiled by Morgan and printed by Miller, detailing Masonic rituals and misdeeds at the highest levels of power. Morgan wasn’t a member of the Masons, but he had convinced other Masons that he was and had been granted access to a neighboring Masonic lodge. Morgan was thus able to witness the Masons’ ceremonies, recording their doings in a manuscript.

News of Miller and Morgan’s impending publication soon began to spread and Masons in neighboring counties began to worry about the disclosures. Reported one Mason at that time: “[I] never saw men so excited in my life.” Committees of Masons were quickly organized to investigate the revelations, and “everything went forward in a kind of frenzy.”

Groups of concerned Masons began harassing Miller and Morgan with prosecutions for petty debt, with the tacit cooperation of the county sheriff, who briefly placed Morgan in jail. Strange men, thought to be Masons from other counties, now began to make suspicious appearances in the villages of Ontario County, putting not just Miller and Morgan on edge but entire towns too.

On Sept. 8 a group of Masons attempted to destroy Miller’s offices. Capping a night of drinking at a local tavern, a group of several dozen men descended onto the print shop. There they found that Miller had convened a posse of his own, equipped with firearms and ready to fight. The Masons retreated, and Miller was safe—for the time being. Two nights later, Miller’s office suddenly erupted into flames, though the fire was detected early and no serious damage was done. Cotton balls dipped in turpentine were reportedly found throughout the print shop.

On Sept. 11 the conflict escalated. A half-dozen Masons showed up at Morgan’s home with an arrest warrant. The charges: petty larceny for stealing a shirt and tie, lent to Morgan by the owner of the town’s tavern, which Morgan had failed to return.

Soon Morgan was being whisked away in a carriage, though reportedly without worry. He apparently thought that testifying that he had simply forgotten to return the items would get him off the hook. He was right. The charges fell through and he was released—only to be immediately arrested again for the outstanding debt of $2.65. This time, the charges stuck.

Morgan spent the following night in jail. The next day, he was forced into the carriage that sped northward out of town, never to be seen again.

That wasn’t the end of the ordeal: A group of Masons soon came back for Miller. On Sept. 12 roughly 70 armed Masons rallied at a tavern while a constable presented the publisher with a warrant for his arrest on questionable charges and conveyed him to the nearby town of Le Roy. Luckily for Miller, his lawyer and an armed posse from Batavia followed along, carrying him back home when the charges fell through.

As Miller and his crew returned to Batavia, the story of his arrest spread throughout the neighboring villages and towns. It was loose ends like Miller, and the family that Morgan had left behind, that would cause the Masons the most trouble. The fate of Morgan’s wife, Lucinda, for example, would help to stoke up sympathy and support for Morgan’s plight, deepening the public’s anger over the Masons’ crimes. The mother of two small children now no longer had a husband to depend on.

But the Morgan affair wasn’t just about the disappearance of one man. The crime had exposed the existence of a powerful group, shrouded in secrecy, manipulating the law for its own purposes. The story of Morgan’s kidnapping, as it was told and retold throughout the coming weeks, focused on how the elite Masons had turned the public interest into a private one and how the government itself may have been perverted in the process.

Two weeks after the abduction, a series of heavily attended public meetings was held. Though the meetings were initially called to solve the mystery of Morgan’s fate, they were equally about calming the public’s fear. There was no guarantee, after all, that what happened to Morgan could not happen to others.

As a result of the Batavia meetings, a panel was established, the so-called Committee of Ten, which began sending agents into neighboring towns to investigate the abduction, gathering facts and taking down testimony. Soon neighboring towns followed suit with committees of their own, all tasked with shedding light on the crime. These public meetings were people’s meetings, and they convened people’s committees: No government authorities were called in because none, many suspected, could be trusted.

The committees were created to calm the public’s sense of fear, but in fact they helped to deepen it. Throughout the months of October and November, citizen representatives of the committees traveled throughout upstate New York spreading the story of Morgan’s abduction, serving to confirm the wild stories local newspapers were already printing about the kidnapping. Those who initially didn’t believe what they read now heard witnesses attest to the truth of the affair. Meanwhile, speculation about Morgan’s fate was becoming more and more sensational. One version of the kidnapping ended with Morgan being murdered in some sort of occult Masonic ceremony, with his throat slit “from ear to ear” and his tongue cut out with a knife.

Illustration from The Mysteries of Freemasonry by Captain William Morgan

Up until this point, the public effort to get to the bottom of the scandal was straightforward, if impassioned. A group of men had conspired unlawfully against Morgan and Miller, and if they were not brought to justice, nothing prevented the same crime from occurring again. Once the criminals had been locked away, everyone could move on—or so, at least, it seemed in the early days after Morgan’s disappearance. But this view would soon change.

Within a few months, the outrage over Morgan’s kidnapping transformed from public fear to political hysteria. Though clearly only a few Masons were guilty of any crime, it was the reaction of other Masons that convinced much of the public that they weren’t dealing with a simple crime but with a widespread conspiracy. Many Masons began publicly—and inexplicably—to defend Morgan’s abduction, and many of them were public figures to boot. “If they are publishing the true secrets of Masonry,” said one former member of the New York Legislature, we “should not think the lives of half a dozen such men as Morgan and Miller of any consequence in suppressing the work.” Another Masonic judge on the Genesee County court stated that, “whatever Morgan’s fate might have been, he deserved it—he had forfeited his life.”

The nascent anti-Masonic movement gained an expanded sense of purpose as the Morgan affair began working its way through the courts. In October, a group of Masons were indicted on charges of rioting and assault for the attempt to imprison Miller. In November, four other Masons were indicted for the conspiracy to abduct Morgan.

By January 1827, the trial was set to begin in Canandaigua, New York, where teams of lawyers, bankrolled by local Masonic lodges, assembled to represent the four Masonic defendants. The district attorney prosecuting the case had amassed a team of his own, which in the end would prevail—though the win would be more symbolic than substantive. The four defendants were sentenced to lenient terms, ranging from two years to one month in prison, convicted only of forcibly moving Morgan from one place to another against his will. What happened to Morgan in the end, and the larger conspiracy behind his abduction, was still conspicuously unsolved.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

If the public wanted justice, this surely was not it. But the trial proved fulfilling in another sense, thanks in no small part to Judge Enos T. Throop. When it came time for him to read the sentencing statement to the four guilty men, Throop read much more than a simple description of their punishment. What he told the Masons, in front of a rapt courtroom, soon to be reprinted in papers across the state, revealed that their trial was about something greater than their offense alone.

Throop began by describing the four Masons’ crimes. Theirs was a “daring, wicked and presumptuous” act, he said, one that had “polluted this land.” The men had robbed the state of a citizen, left the victim’s wife and his children “helpless,” and somehow shielded the rest of the culprits from being brought to justice. But this act on its own was not even the “heaviest part of your crime,” as Throop explained:

Your conduct has created, in the people of this section of the country, a strong feeling of virtuous indignation. The court rejoices to witness it—to be made sure that a citizen’s person cannot be invaded by lawless violence, without its being felt by every individual in the community. It is a blessed spirit, and we do hope that it will not subside—that it will be accompanied by a ceaseless vigilance, and untiring activity. … We see in this public sensation the spirit which brought us into existence as a nation, and a pledge that our rights and liberties are destined to endure.

The public’s outrage, in other words, was now no longer about one crime, or even the conspiracy to cover it up. It was about the “spirit which brought us into existence as a nation,” in Judge Throop’s words, and about the fear that this spirit was threatened.

What Throop saw in the public indignation was a dedication to America’s founding spirit. The citizens, it seemed, were willing to enforce the laws themselves, if that’s what it took to protect American ideals. What began as the public’s reaction to a local kidnapping was now evolving into a common dedication to protect America’s core values.

Freemasonry served as a compelling symbol for the real threat that many Americans were facing. The 1820s were a decade of great uncertainty, one in which industrialization posed profound challenges to American society. The rise of manufacturing threatened to reorganize the American labor force on a massive scale, as did immigrants and population booms in eastern cities.

“In fastening on Masonry as the foremost evil in the Republic,” writes historian Paul Goodman, “Antimasons were responding to the emergence of industrial society which clashed with the remnants of a pre-industrial order.” America, many thought, was entering an era of chaos, and one in which the principle of equality was fundamentally threatened.

With the trial now complete, the movement reached another turning point. Furious over the court’s inability to bring all of Morgan’s abductors to justice, alarmed members of the public began to advocate action in the political realm. In February, a joint meeting was held by the people of the towns of Batavia, Bethany, and Stafford, who resolved to “withhold their support at elections from all such men of the Masonic fraternity.” The people in the town of Seneca committed that “they would not vote for Freemasons, for any offices whatever.” And it wasn’t only Masonic politicians who found themselves under attack. Newspapers run by Masons, which many felt had been conspicuously silent on the Morgan affair, were also the target of the public’s ire. A meeting of the towns of Pembroke and Alexander passed a joint resolution to “discourage the circulation of any paper” that did not cover the Morgan affair accurately. In meetings throughout the towns of upstate New York, scores of similar resolutions followed suit. By February 1827, five months after Morgan had gone missing, the Anti-Masonic Party was born.

And by the end of the year, the party was already sweeping the polls in New York. In the elections of 1827, for example, the party of the sitting U.S. president, John Quincy Adams, would elect 12 members to the New York Legislature while the Anti-Masons would elect a shocking 15. The following summer, just a few months before the national elections of 1828, Adams himself had openly aligned himself with the Anti-Masons by declaring that, “I am not, never was, and never shall be a Freemason”—proving that the party had jumped from a statewide political phenomenon to become a national one.

The 1828 elections marked a major turning point for the Anti-Masons. As the movement spread from New York to states like Vermont, Ohio, Massachusetts, and Maryland, Anti-Masonic candidates won seats in state legislatures across the country. At the federal level, the Anti-Masons became the first third party in the United States to send candidates to Congress, electing nearly a half-dozen members to the House of Representatives.

Perhaps more notably, the Anti-Masons gained the mantle of the opposition party in the 1828 elections. President Andrew Jackson, an avowed Mason himself, had ousted Adams and was now in power. The Anti-Masons now not only had a prominent political platform, in both state and national legislatures. They had a villain in the White House.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

By 1830, the push for a national organization was under way, aided by opposition to Jackson and the growing sense that American society was fracturing. On Sept. 11 of that year, precisely four years after Morgan had been abducted from his Batavia home, the Anti-Masons held their first national convention in Philadelphia, with delegates from New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Ohio, Maryland, and Michigan in attendance. It was here that the party hatched its grandest plans for national influence—and, ultimately, where the seeds of the movement’s downfall were first sown.

With growing national power came increased opportunity, but divisions were already stirring within the Anti-Masons’ ranks. For many of the moderates in the party, some of whom viewed Andrew Jackson’s policies as a danger equal to, if not greater than, the threat posed by Masonry, the need to build coalitions with opposition figures outside the Anti-Masonic Party soon became clear.

The problem, however, was that a large number of Anti-Masons, zealous in their beliefs, did not have the stomach for compromise—they simply refused to deal with any politicians who would not denounce all of Freemasonry. Questions about the party’s ability to handle routine political tasks now began to be posed with increasing frequency. Would the Anti-Masons be able to strike political bargains at all? Would allying themselves with other Jackson opponents undermine their cause? Put simply, would compromise dilute the Anti-Masons’ strengths or would it make the party stronger?

In the face of such disarray, the delegates agreed to postpone major decisions, such as whom to nominate for the 1832 presidential election, until the following September, when the party would hold a national nominating convention, the first of its kind in American politics, and one that is emulated by political parties to this day. Instead of party leaders choosing whom the convention would nominate, delegates to the convention, each representing their local supporters, would elect the party’s candidates. This new type of convention was a way of bridging ideological differences within the party, of importing the democratic process into the party itself. At the same time, it underscored the party’s increasingly weakened leadership.

The divisions between the moderates and the radicals in the party would only grow. One newspaper covering a local 1831 Anti-Masonic convention highlighted the now increasingly popular view “that Antimasonry had other and higher objects in view than the prostration of the Masonic fraternity.” Samuel Miles Hopkins, a longtime New York politician and one of the state’s most prominent Anti-Masons, declared that Andrew Jackson was a greater threat to the country than Freemasonry and that in the previous election he himself had voted for Masons rather than let pro-Jackson candidates win. By 1831, a year before the presidential election, the Anti-Masonic Party was rotting from within.

But rising tensions would not stop the ambitions of the party at large, which believed it had found the perfect 1832 presidential candidate in William Wirt, a Virginia politician and former attorney general, and one of the last vestiges of old-style American politics.

Wirt was a stern moralist and a devoutly religious man, and he had been tapped by Thomas Jefferson himself as a political heir. “You will become the Colossus of the republican government of your country,” Jefferson had once assured him. Wirt’s concern with America’s moral status echoed many of the Anti-Masons’ deepest concerns. It was the selfish pursuit of profit that Wirt thought was the animating evil of the times. The growing object of Americans of every stripe was simply “to grow rich: a passion which is visible, not only in the walks of private life, but which has crept into and poisoned every public body.” What Wirt identified as the flaws in American society were the same evils that the Anti-Masons saw in Freemasonry itself: a system in which the few benefited at the expense of the many.

There was one problem: Wirt had himself once been a Mason and had never explicitly renounced the order. Now, he was calling the entire conflict between Masonry and Anti-Masonry “a fitter subject for farce than tragedy,” and bemoaning the “wild and bitter and unjust persecution against so harmless an institution as Free Masonry.”

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

The most radical of the Anti-Masons were obviously outraged by Wirt. Increasingly sidelined, the radicals within the party watched as Wirt was selected to carry the Anti-Masonic banner in the fight against Andrew Jackson, allying with other elements of the opposition.

But by and large the rest of the party supported him, perhaps to a fault. Wirt would ultimately carry only the state of Vermont in the presidential election, winning Anti-Masonic counties in states across the country but falling severely short of any meaningful support at the national level. After Wirt’s failed candidacy, the Anti-Masonic Party “seemed as if by magic, in one moment annihilated,” wrote one 19th-century historian. Men “who had repeatedly most solemnly declared, they would never vote for an adhering Mason for any office whatever, in one day, ceased to utter a word against Masonry.”

And thus the party’s tenure in the national spotlight came to an end—though not without lasting effects. The fraternity that the party had set itself against was forever damaged. Over the course of the hysteria, Masons across the country resigned or denounced their membership, and hundreds of lodges were shuttered. “Lodges by scores and hundreds went down before the torrent and were swept away,” according to one Mason at the time. “In the State of New York alone upward of 400 lodges, or two thirds of the craft, became extinct.”

This article is adapted from Andrew Burt’s book, American Hysteria: The Untold Story of Mass Political Extremism in the United States.

But the rise of the Whigs did not mean the Anti-Masonic cause had passed. Throughout the following decade, a few politicians would make their names proclaiming the evils of Masonry. Some of them faded into obscurity, but others met with limited success. As late as 1836, Pennsylvania’s Thaddeus Stevens led an Anti-Masonic committee in the state Legislature that held public hearings on the threat of Masonry, interrogating Masonic witnesses and drawing some national attention. Stevens would ultimately rise to become a congressman, and later one of the U.S. House of Representatives’ most outspoken abolitionists during the Civil War.

In Massachusetts, Ohio, and Vermont, local groups of Anti-Masons met to purge their states of Freemasonry’s influence throughout the 1830s as well, and some still harbored national ambitions for their party. But cracks had emerged in the Anti-Masonic movement that were too big to plaster over, and no longer did the threat of Freemasonry captivate as large a political audience or maintain its wide appeal. The Anti-Masonic movement now operated on the fringes of American political discourse.

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

By the 1840s, the Anti-Masonic Party was dead and gone, its most loyal adherents dismissed as zealots. But it left behind a powerful legacy: The party established a pattern that future episodes of political hysteria would repeat across American history, from the Red Scares of the 20th century to the anti-Sharia movement of today.

Each movement claims to protect our nation from an existential threat. Each parlays fears of shadowy actors undermining our democracy into populist calls to action. During the period of McCarthyism, more than 13 million Americans—roughly 20 percent of America’s working population—signed loyalty oaths. Today’s anti-Sharia movement—which seeks to demonize Islam, the world’s second largest religion—has succeeded in banning Islamic law in several states. And while movements of political hysteria always claim only to want to rid society of a single, dangerous ideology, its partisans ultimately jeopardize the very values they claim to protect: that we are an open-society committed to the coexistence of many groups and belief systems, a country founded on the principles of freedom and equality for all.

As for the former Anti-Masons themselves, many of the movement’s leaders went on to bigger achievements even after the demise of their party. Millard Fillmore, a New York Anti-Mason from the start, became president in 1850. William Seward, another New York Anti-Mason, became Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, serving as a key member of the president’s wartime cabinet. William Morgan’s lonely widow, Lucinda Morgan, would herself go on to further renown. She moved west and reportedly remarried a man named Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or the Mormons—a group that, like the Freemasons, would soon find itself the target of future political crusades.