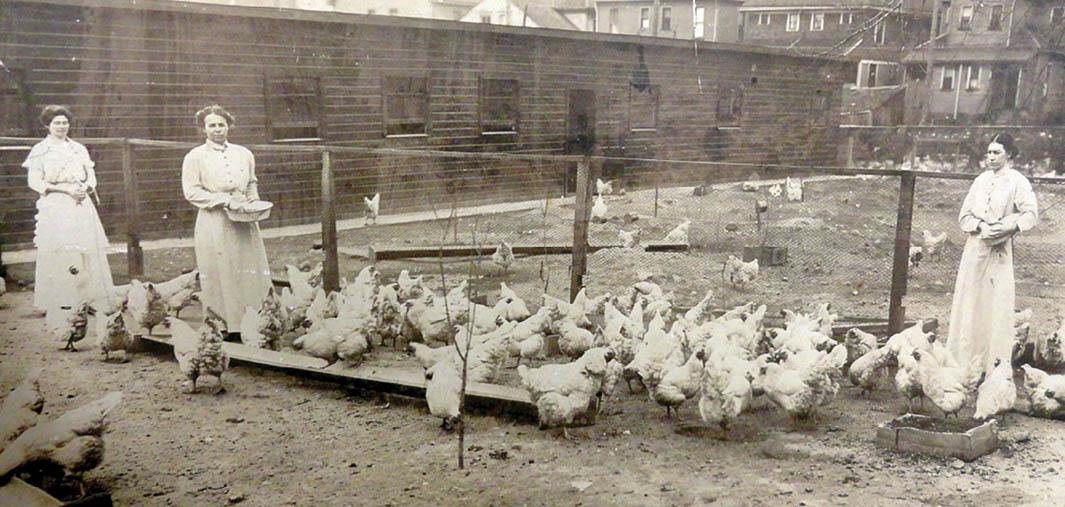

In 1873, two Quaker reformers living in Indiana, shocked by allegations of sexual abuse of female prisoners at the state’s unisex institution, pushed the state to fund the Indiana Reformatory Institute for Women and Girls: the first totally separate women’s prison established in the United States. For years, Rhoda Coffin, who lobbied for the prison and then joined its first board of visitors, and Sarah Smith, the founding superintendent, enjoyed a historical reputation of benevolence. Coffin and Smith, the story went, started an institution that prioritized reform of inmates over punishment. If their approach was invasive and personally constrictive—the institution focused on reintegrating prisoners into Victorian gender roles, training them (as the prison’s 1876 annual report put it) to “occupy the position assigned to them by God, viz., wives, mothers, and educators of children”—at least this new kind of prison provided safe surroundings and was bent on giving troubled inmates a second chance at life.

Recently, a group of women currently incarcerated at the 142-year-old institution (now called the Indiana Women’s Prison) began to pore over documents from the prison’s first 10 years. They had set out on an ambitious project: to write a history of the institution’s founding decade, one that tells quite a different story from the official narrative. What happens when inmates write a history of their own prison? In this case, the perspective that the group brought to the project took what inmate Michelle Jones, writing in the American Historical Association’s magazine Perspectives on History, calls “a feel-good story” about Quaker reformers rescuing women from abuse in men’s prisons and turned it into a darker, more complicated tale.

The researchers focused their attention on allegations of wrongdoing at the prison, looking at previously discredited testimonies of prisoners who claimed to have been physically abused and at the activities of a prison doctor who had some very Victorian ideas about women and sex. They began to unravel a long-standing mystery: Why didn’t the prison incarcerate any prostitutes in its early years? They presented their findings at academic conferences and published papers in journals. And they did all of it without access to the Internet.

Kelsey Kauffman, who spearheaded the project, holds an Ed.D. in human development, worked as a correctional officer, wrote a book about correctional officers, and taught college classes in writing at two men’s prisons.* Kauffman was dismayed when the Indiana state legislature canceled funding for nonvocational college programs in prisons in 2012. At the suggestion of the Indiana Women’s Prison’s superintendent, and working with two other educators, she started a new, grassroots program of college courses at IWP.

Kauffman’s book contained a chapter on prison history in Massachusetts, and she had long been interested in the idea of leading a class in writing a history of the IWP. She told me that she tried the project with her college students at DePauw University, to no avail. “They never asked an interesting question,” she told me. “To some extent, you can’t blame them for that, because they know nothing about prisons. It doesn’t relate to their lives.” Kauffman resolved to try the subject out on students who knew the subject firsthand.

* * *

IWP is a maximum-security facility, and many of Kauffman’s 20 students were serving sentences for violent crimes, ranging from robbery to murder. Some had just started taking college classes, while others had been at the facility long enough to have graduated with a degree through the prison’s old college program. Michelle Jones and Anastazia Schmid, the two researchers I interviewed for this story, each earned a bachelor’s from Ball State University that way. Jones, 43, has been at the prison since 1996; Schmid, 42, has been incarcerated since 2001.

Photo by Liz Kaye

The group met once a week for three-hour sessions. Kauffman set out to convince them that they could make real interventions in the history of 19th-century women’s prisons, publish and present their research, and eventually write a book. At the beginning of the project, some of the student researchers were dubious of those ambitions. “A lot of people did not believe it,” Jones told me. “I was skeptical.”

Kauffman began by splitting the group of researchers in half. Some began with secondary research, reading histories that covered related subject areas (19th-century mental hospitals, the history of medicine). The others began looking at primary sources from the prison’s history, concentrating on a topic: health care, the economy of the prison, food. Jones began to wrangle data from the prison registries, which Kauffman had scanned at the state archives, printed, and brought in for the researchers to use.

Photo by Liz Kaye

Research in the prison is difficult. I asked Jones about the library’s stock of books. “Our recreational library is very good,” she said, “but it’s limited predominantly to fiction, so when it comes to doing research, particularly if you’re interested in the 19th century … it’s just not going to be there.” Interlibrary loan is slow. The IWP researchers followed the time-honored approach of tracking down new references using the footnotes and bibliographies of the books they were currently reading, but the new requests sometimes took months to arrive. Kauffman and other volunteers tried to fill the gap by providing books themselves, but with a long list of research requests, they couldn’t always access titles quickly enough. The digital databases and online archives and collections that historians now take for granted were not available to the women. The researchers were not just researching the 19th century; they were working at a 19th-century pace.

Sarah J. Smith. Courtesy of the Indiana Department of Correction Virtual Museum.

As the group’s research inched forward, the two women who founded the prison—Rhoda Coffin and Sarah Smith—began to come in for their share of skeptical analysis. The founders’ story—female reformers who “rescued” women from sexual abuse in an institution full of predatory guards and prisoners—had traditionally been one of exemplary Christian female heroism. In historical sources, the women were described using the Victorian rhetoric of womanly virtue, with Smith in particular held up as an example to sinning prisoners under her care. “We referred to Sarah Smith as ‘Saint Sarah’ in our class,” Kauffmann told me, since so much contemporary literature lauded the prison’s first superintendent for her forbearance and purity.

Less complimentary descriptions of the two women fade into the background in most histories, which discuss their work as part of a largely benevolent movement toward prison reform for women in the late 19th century. Kauffman’s researchers were therefore surprised to read a published report of an 1881 inquiry into mistreatment of prisoners, in which Smith had been accused of humiliation, assault, and “dunking” of prisoners who didn’t follow the institution’s rules. Several former prison employees testified to witnessing Smith hit the prisoners, with two saying that they had seen Smith “pull their hair and pound their heads against the wall.” According to testimony, prisoners were also put into solitary confinement and denied food and medications. Smith and the prison were exonerated of these charges, but most of the researchers believed the inmates, nurses, and other staff whose testimony appeared in the report, and the class debated what might really have happened, arguing over how harshly to judge Smith for the punishments used at the prison she ran in the name of mercy.

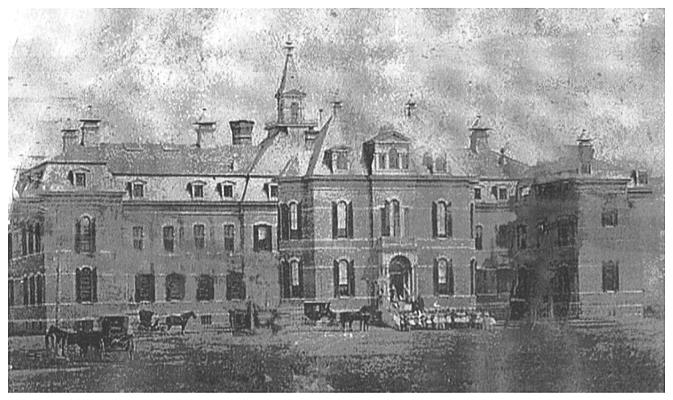

Indiana Women’s Reformatory, 1873. Courtesy of the Indiana State Library.

As for Coffin, who was not involved in the daily administration of the prison, the researchers discovered that her life had its own troubling chapters. In 1884, Coffin’s husband, Charles, who ran a bank, was found to have embezzled, cooked the books, and extended unsecured loans to his sons, while living a luxurious lifestyle financed by this malfeasance. Many of the people harmed by the bank’s eventual collapse were working-class depositors. The scandal forced the Coffins to move from Richmond, Indiana, to Chicago. While it’s hard to know what Coffin knew about her husband’s wrongdoing during the years when he carried out his crimes, the students found themselves unable to forgive her, insisting that she couldn’t have been completely ignorant of his actions, and finding hypocrisy in the contrast between her humble public posture and her well-to-do life.

With Kauffman’s help, the group began to test out their ideas on audiences of historians. The prison agreed to allow incarcerated researchers Leslie Hauk, Kim Baldwin, and Lori Fussner present a paper on Coffin and Smith by videoconference at the Indiana Association of Historians conference in March 2014. The authors were not sympathetic to their subjects. “Why have historians seemingly given [Smith and Coffin] a free pass for this behavior?” the three asked. Pointing out the disparity between the small “property crimes” committed by many of the prison’s working-class inmates at the time and the large amounts of money that Coffin’s husband caused his depositors to lose, and finding themselves unable to excuse Smith for the behavior reported in the 1881 inquiry, the authors argued that the history of the prison’s founders is incomplete without this information: “There seems to be a fulgent disparity in the consequences for the crimes of the powerful, like torture and bank fraud, and the punishment dispensed by the courts and by Ms. Smith for the slightest infractions of the poorer classes.”

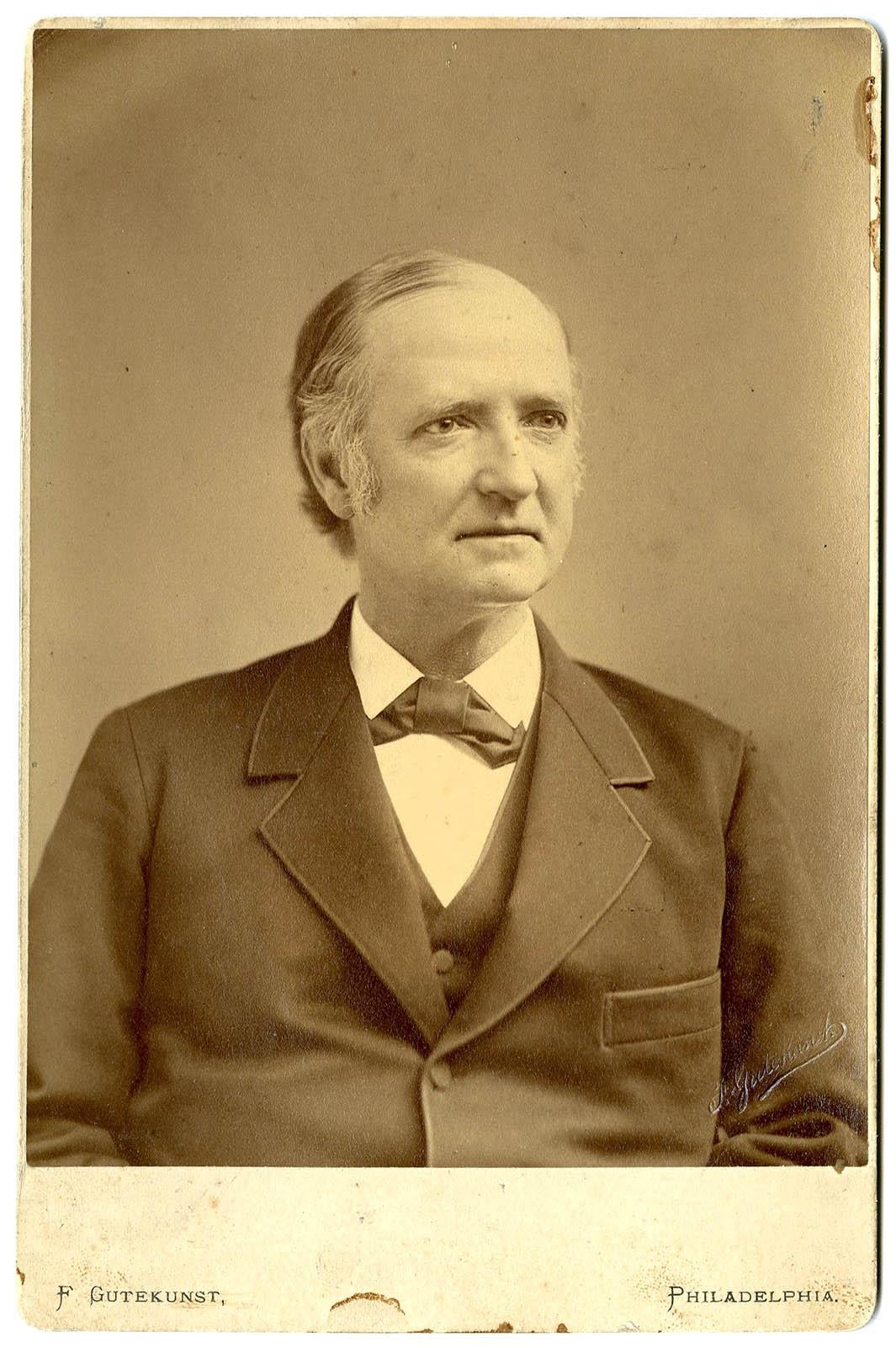

Theophilus Parvin. Courtesy of Thomas Jefferson University.

In another conference paper, Anastazia Schmid presented her research on the history of health care in the prison. Schmid wrote about the doctor Theophilus Parvin, who was the prison’s physician between 1873 and 1883. Comparing Parvin’s reports of his treatment of prisoners with his published articles in medical journals, Schmid became suspicious. She likened Parvin to Dr. J. Marion Sims, another respected 19th-century gynecologist who had perfected a technique for repairing vesicovaginal fistula (a tear between the urinary tract and the vagina, often caused by difficult childbirth) by experimenting on enslaved women. (Kauffman said, “It was Ana who made the link to Marion Sims. I had never heard of Marion Sims—I had no idea.”) Schmid raised the possibility that Parvin might have carried out his own experiments on the women at the prison.

Presenting on the topic via videoconference at the 2014 meeting of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences, Schmid pointed out that although Parvin never officially reported carrying out research using female inmates as test subjects, a prisoner who testified at the 1881 investigation mentioned a mysterious “operation” that was performed after she had misbehaved. Schmid suggested that this operation might have been an ovarectomy or a cliterodectomy—two operations Parvin had advocated for treatment of “hysteria” in other contexts. The researchers also identified three prisoners whose case studies Parvin included in an article for a medical journal, lending further credence to the idea that his decade at the prison had yielded experimental results procured from patients who may or may not have consented.

When discussing Parvin, Coffin, and Smith, Kauffman and the researchers sometimes came into friendly conflict, with Kauffman pushing for more evidence and the group insisting that their personal experience better equipped them to judge the historical record. “Dr. Kauffmann and I kind of went around and around a few times on some of my theories, and at one point in time I had to kind of get brutally honest with her,” Schmid says. “When she was saying, ‘Ana, how do you know? Where are you getting this?’ I had to divulge some of my personal story and say, ‘Dr. Kauffman, I know because I am the modern version of the women I’m talking about.’ ”

* * *

While some researchers refocused the history of the prison on the moral dubiousness of its authority figures, others took a different direction, arguing for a redefinition of the accepted chronological narrative generally applied to the history of women’s prisons. This turn came about because Jones, by her own admission, fell in love with the data found in the prison registries. (“I was invested in these women. I felt like I knew them,” Jones told me.) Jones took charge of toting up the information available in the registries: the crimes for which inmates were convicted, their races, their past criminal records, processing officials’ comments on their characters. She found a glaring absence: None of the prisoners had been incarcerated for prostitution. While previous researchers had encountered this discrepancy (see this table in historian Estelle Freedman’s 1984 book Their Sisters’ Keepers), Jones kept wondering about the reason prostitutes might have been missing. “Hadn’t the prison been created for all the ‘fallen’ women?” she wrote. “If they weren’t at IWP, where were they?”

Admiring Jones’ persistence in asking this question, Kauffman told me: “I came back with all these dumb excuses. Maybe there wasn’t much prostitution. … Maybe they didn’t criminalize it … ” None of them held up. Eliminating alternative explanations, Kauffman eventually had to admit that the absence was a telling one. By sheer luck, an archivist at the Indiana State Library who was helping with the project found a newspaper article that led the group to a possible explanation. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic organization, had opened a House of the Good Shepherd in Indianapolis the same year that the prison was founded. With the help of research librarian Monique Howell, the group discovered that some county courts sent convicted felons to that location. Jones hypothesized that this was where the “fallen women” ended up.

Jones and fellow researcher Lori Record found 15 other Catholic reformation houses for women that were established in the United States before the Indiana Women’s Prison. Writing in the Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences in 2014, Jones and Record argued that these “Houses of the Good Shepherd” were a parallel system, prisons in function if not name that operated alongside the ones run by the state. Jones and Record wrote that Houses of the Good Shepherd took inmates sentenced by criminal courts, held them involuntarily, and isolated them from the outside world. Citing contemporary reports about poor treatment of prisoners at these houses, the two researchers argue that they should be considered the American equivalent of Magdalene laundries—the infamous 19th- and 20th-century Irish institutions that involuntarily confined women who had been found to be “wayward.” The Sisters of the Good Shepherd managed a Magdalene laundry in Ireland, and the researchers saw correspondences between that history and the story of the American Houses of the Good Shepherd.

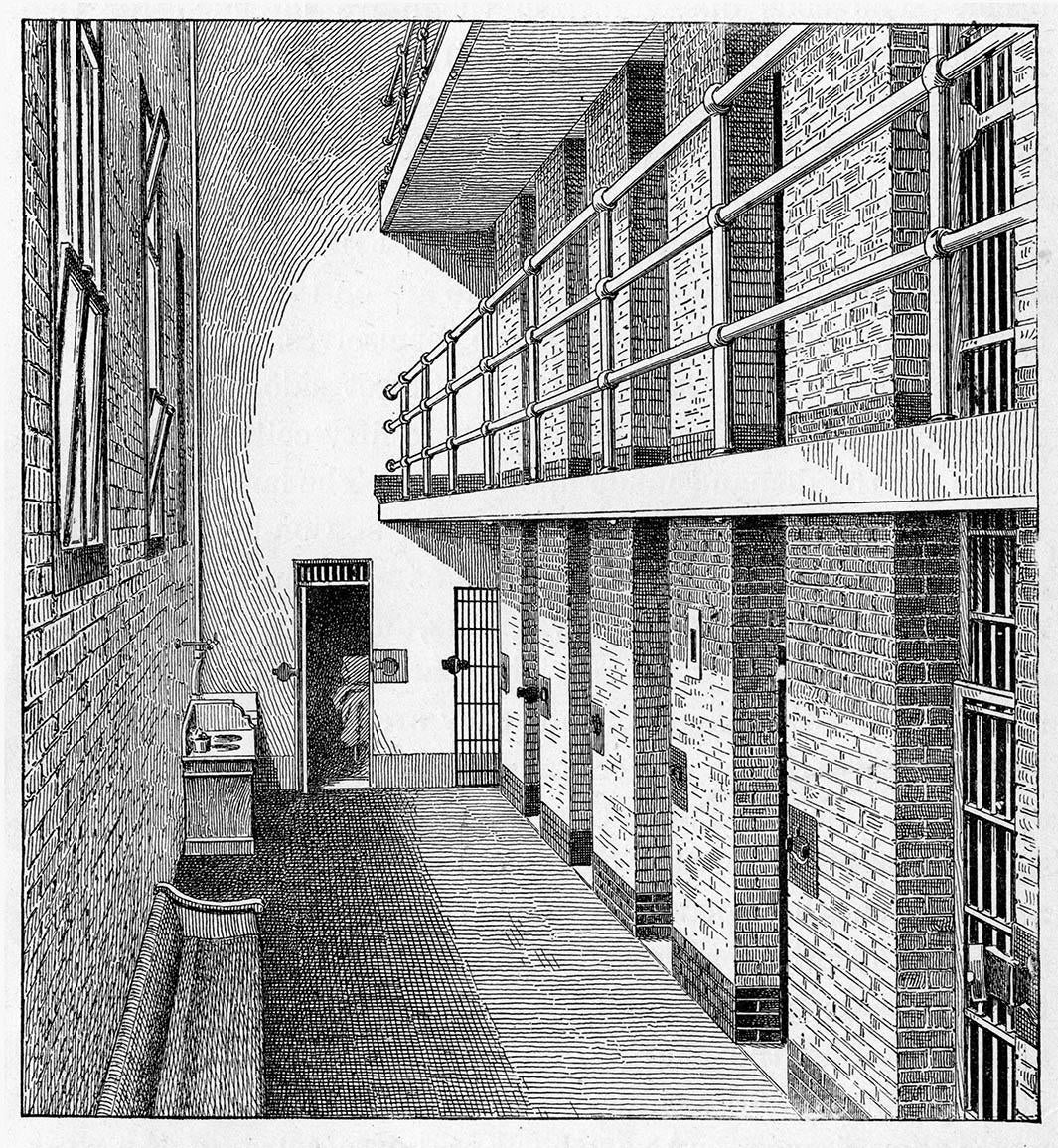

Prison cells for women in the Tombs, New York, late 19th century. Illustration by Helen Campbell/Darkness and Daylight: Lights and Shadows of New York Life/Interim Archives

While historian Sharon Wood, who is a professor at the University of Nebraska–Omaha, hesitates to equate American Houses of the Good Shepherd with Irish Magdalene laundries, she compliments the students’ work, writing in an email to me that it overlapped with and enhanced her own research on “erring” girls who were sent to Houses of the Good Shepherd from the courts of Davenport, Iowa, in the 1890s. Jones, Wood wrote, described “a bifurcated system, a state-run prison for women convicted of various crimes (but not prostitution), and a private reformatory for women accused or convicted of sexual misconduct, operated by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd.” Wood found the same dynamic at play in Davenport in the 1890s and was delighted to see that the Indiana Women’s Prison researchers had uncovered this pattern in Indianapolis. “As far as I know, no historian has pursued this topic, so it was surprising and wonderful to read about what the students at IWP found,” she wrote.

* * *

In the wake of their initial success, the IWP researchers are now turning from shorter articles to a book-length work. Jones told me that she is going to return to her data, research some higher-profile women who ended up at the prison by committing crimes that garnered newspaper coverage, and write a narrative that describes the data while anchoring it in their cases. Schmid wants to write more about the relationship between present-day abuses of prisoners and the kinds of stories she sees in the history of IWP.

The researchers’ ambitions are still circumscribed by their imprisonment, however, and by the labor involved with procuring materials for incarcerated researchers. In her own article for Perspectives, Kauffman issued a call to arms to retired historians and others who might be interested: “I need help tracking down myriad leads on such topics as Sarah Smith’s roots in England; the history of the Magdalene laundry in Buffalo, New York; 19th-century sewage systems; and the incidence of female circumcision in the 1870s. We would be delighted and grateful to have your help.” (Her contact information can be found here.)

*Correction, March 23, 2015: This piece originally stated that Kelsey Kauffmann has a Ph.D. She holds an Ed.D.