Cornelia Hancock, a resident of Hancock’s Bridge, New Jersey, and 23 years old in 1863 when the Battle of Gettysburg ripped open the Pennsylvania countryside, had an “average” nose. “The nason and the rhinion, which made up the bulk of the length of that nose, were quite sweeping but not overly, the nostrils were neither large nor small, only slightly flared,” Mark Smith, professor of history at the University of South Carolina, writes in his new book The Smell of Battle, The Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War. “The tip was button-ish, but this was not necessarily a bad thing,” since it put her within the range of feminine nasal ideals of the day.

Hancock, intent upon serving as a nurse in the aftermath of the battle, brought that average nose to Gettysburg, where she was too late to smell the flowering peach blossoms and the saltpeter of expended gunpowder, but in plenty of time to smell the dead. She wrote home:

A sickening, overpowering, awful stench announced the presence of the unburied dead upon which the July sun was mercilessly shining and at every step the air grew heavier and fouler until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be seen and felt and cut with a knife …

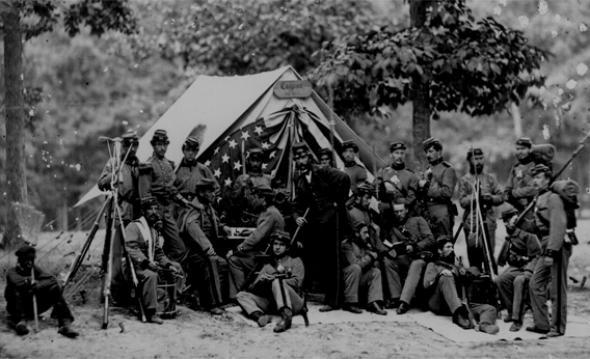

Hancock, Smith writes, was so overcome by the smell that she viewed it as an oppressive, malignant force, capable of killing the wounded men who were forced to lie amid the corpses until the medical corps could reach them. Hancock’s account, vivid in its horror, proves the limitations of the visual record of war. No photograph of the aftermath of the battle, writes Smith, could “capture the sounds, the groans or the rustle of twitching bodies”—and no image could ever capture that smell.

The Smell of Battle is an unconventional history of the Civil War, written with special attention to olfaction, touch, taste, sight, and hearing. It joins other recent histories of the war—Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War; Michael C.C. Adams’ Living Hell: The Dark Side of the Civil War—in trying to represent the war’s massive levels of death and disruption so that 21st-century readers will really feel the history, deep in their bones. In episodic chapters that look at familiar historical evidence in new ways, Smith considers the fall of Fort Sumter in its terrifying loudness, the visual confusion of war at the first Battle of Bull Run, the stench of Gettysburg, the taste of subpar food inside the besieged city of Vicksburg, and the awful sensation of full-body confinement inside the doomed Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley.

Smith’s book forces us to set aside our lofty notions about the war and regard it from a human perspective. “This war was a war about some of the greatest and most noble ideals in American history,” Smith told me in an interview. “This was about freedom, questions of national identity, questions of sovereignty, questions of personal liberty. And I’m not denying all of that. What I am saying is that we have to be very careful not to elevate those noble questions so much that they cloud or occlude our understanding of war.” Sensory history, Smith said, is one way to help us understand how it would have felt to be there: trapped on the Hunley, straining to get enough oxygen from the scant supply of air, shivering in the humid cold, and laboring mightily to move the boat forward. “Underwriting all of those ideals,” he continued, “we have a very gritty, deeply unpleasant human experience. And that human experience can be best excavated by an attention to the sensory experiences of war.”

Sensory history, The Smell of Battle makes clear, is more than just an exercise in providing colorful detail (though the book is quite colorful, and, for all its awful subject matter, eminently readable). The goal is to understand how the people of the past felt about the sensations they reported. A smell or tactile sensation may change in meaning over time. Certain sensations may seem universally understandable—the pain of a blister hasn’t changed in 150 years—and yet that pain might mean something different to a person raised to prize smooth hands as a mark of social standing, or something else to somebody who lived at a time when broken blisters could lead to untreatable infections.

In the case of the Civil War, Smith argues that the conflict seemed particularly jarring to the Americans living through it because they were proud to consider themselves modern—able to control their sensory environment. New ideas about environmental sanitation, for instance, had begun to yield cleaner cities, with fewer odors of waste and decay. “A war,” Smith says, “doesn’t obey any of those mandates, any of those protocols.” The raucous, “transgressive” smells and sounds of war were “insistent” and “disempowering”; “people felt as though they were hostage” to these incursions. For a society deeply invested in the relationship between order and modernity, the sensory changes of the war felt “atavistic.”

The senses also had social meaning to mid-19th-century Americans, marking differences between types of people. A 19th-century woman like Cornelia Hancock might process the smell of Gettysburg differently than we do because of the contemporary belief that cultivated people had sensitive noses and should guard themselves from unpleasant odors. The besieged citizens of Vicksburg weren’t merely turned off by the poor provisions during the long siege by Grant’s army; they were horrified at the idea of eating the same kinds of foods as the enslaved people around them. In the South, a sophisticated sense of taste was a marker of social status. Black people’s mouths and palates, by contrast, were considered by Southerners to be “physically unrefined and aesthetically immature,” Smith writes, a stereotype “justifying the allocation of plain, functional, and flavorless food to slaves on plantations.” White residents eating a monotonous cornbread and bacon diet inside the crowded city or in their cave shelters felt their social boundaries collapsing, even as they grew hungrier and hungrier.

A book like Smith’s, which tries to put reports of sights, sounds, and tastes in context, is a powerful argument for the importance of reading original historical sources while trying to understand the social mores of the time. Re-enactments that try to recreate the sights, sounds, and smells of 19th-century war will always be limited by the 21st-century bodies we bring to them—we just don’t experience the sensations the way a 19th-century American would. “I could have sold a lot more [books] if I had written this as a handbook to re-enactment,” Smith says. “But I can’t do that, I wouldn’t do that, and the reason why is that history matters.” A re-creation of the visual, acoustic, or olfactory environment of the Civil War is impossible—and even if we were willing to kill hundreds of horses and let them rot, or to confine ourselves underwater in dangerous prototype submarines, we would never be able to perceive these events as our forebears did.

Recalling an exhibit on trench warfare that I saw at the Imperial War Museum in Manchester, England last summer, which asked me to flip up the lid of a canister to smell something that could be rum, cigarette smoke, wet clothes, cordite, or human remains, I asked Smith if he has the same objections to museum exhibits that incorporate smells. “Sensory history has this kind of universal appeal to people,” Smith says. “You find some museums adopting this conceit: Listen to the past, touch the past. And what you’re really doing is no such thing. You’re using your own moment to mediate an imagined past.” I can flip up the lid, smell cigarette smoke, and associate it only with past good times at a bar or a party. The feeling of historical closeness these exhibits offer can be deceptive.

The Smell of Battle’s most effective passages demonstrate to the reader how the men and women of Civil War America experienced the conflict’s sensory assault. One of these is in the conclusion, which contrasts the heavily enforced quietness of enslaved people before the war with their vocal celebrations afterwards. As the Yankees marched through the South, “black voices [were] no longer constrained,” Smith writes. Their cheers and songs “punctured the southern air as surely as the first shells launched at Fort Sumter those long years before.” The war, Smith reminds us, produced sounds, smells, and tastes of liberation as well as destruction—a reminder that the “noble” stories of the war are inextricably linked to its sweat, blood, and stink.