Two weeks ago, Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf wrote a letter to Barack Obama concerning the outbreak of Ebola in her tiny West African country. The message was a desperate one, the tone pleading. “I am being honest with you when I say that at this rate, we will never break the transmission chain and the virus will overwhelm us.” A former finance minister and World Bank official, Johnson Sirleaf is not one for histrionics.

At the time, this worst outbreak in Ebola’s 40-year recorded history had claimed some 2,218 lives, more than 1,000 in Liberia alone, though no one could be sure how close these numbers were to the reality in the field. (As of this week, the virus had added hundreds more lives to its grisly harvest.)

Photo by Michel du Cille/The Washington Post

Johnson Sirleaf was tactful with Obama, as any leader of a small country pleading with a U.S. president must be. She said nothing of the risible inadequacy of his initial offer of help—a 25-bed facility in the Liberian capital of Monrovia to treat stricken health care workers.

In any case, Obama got the message. His decision last week to commit $763 million in emergency aid funding and 3,000 military personnel to build and staff portable hospital, lab, and training facilities across Liberia is on a scale unprecedented in U.S. history. In his address from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Obama cited humanitarian concerns and the threat the epidemic posed to global security.

Photo by Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

What this son of an African father did not mention was the special obligation that America owes Liberia—an obligation that has through history been more often honored in the breach—though some of the more historically minded pundits in Washington did note that it might have played a role in the Obama administration’s choosing Liberia as the focus of its anti-Ebola efforts. Africa’s first republic is America’s half-forgotten stepchild.

You might remember the vague outlines of the story from American history class. It’s typically a sidebar to the heroics of abolitionism and tragedy of sectional strife in the run-up to the Civil War—freed slaves being sent back to Africa and founding a country named for liberty itself. Maybe you keep one of those old imperial maps in your head, with Liberia’s tiny un-tinted patch on Africa’s belly, surrounded by British pink and French blue.

In fact, Liberia was not really founded by freed slaves. Of the nearly 100 settlers first dispatched in 1820 to West Africa’s shores, not a one had been a slave. They were free black men, women, and children, largely from New York and Pennsylvania. The first of the thousands that followed them were mostly free, too.

But in an America where race was destiny and a dark complexion a badge of servitude, free blacks were unwanted, an affront to whites’ notion of the God-given order of things. They were also, in early 19th-century America, the fastest-growing population in the land, descendants of runaways during the Revolution and those manumitted by enlightened masters, like George Washington, who took the words “all men are created equal” to mean what they say.

Their presence in America stoked equal parts fear and contempt. In the paranoid depths of the white imagination, they drank and they fornicated, they stole and they fenced goods pilfered by slaves. Worst of all, they infected their enslaved brethren with dreams of freedom and idleness. There simply was no place for them in a white man’s republic.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

With that in mind, on a winter solstice’s evening in 1816, some of Washington’s most powerful movers and shakers gathered at a popular watering hole to found the American Colonization Society: Its mission was to transplant the country’s 200,000-plus free blacks to West Africa. Today, we would call it ethnic cleansing. To meeting chairman Henry Clay, who as U.S. speaker of the House was the second-most-powerful politician in the country, it was enlightened benevolence: “Can there be a nobler cause than that which, whilst it proposed to rid our country of a useless and pernicious, if not dangerous portion of its population, contemplates the spreading of the arts of civilized life, and the possible redemption from ignorance and barbarism of a benighted quarter of the globe?” (That is, Africa.)

Clay, however, never did explain what alchemy he expected to occur during the Atlantic crossing that would turn a “useless and pernicious” people into the heralds of “civilized life.” Nor did he say on whose dime and what ships this exodus would occur. In the end, the ACS pried a paltry $100,000 from Congress for the enterprise.

But the ACS faced an even bigger problem than these. The vast majority of America’s free black population made it very clear they had no intention of going. At a 3,000-strong meeting in Philadelphia, home to the nation’s largest free black community, the voiced “nay” vote, by one witness’s account, “seemed as it would bring down the walls of the [Bethel Church].” The free black community was united in the idea that free blacks had as much right to be in American as any white man, while many saw emigration as abandoning their brethren in slavery, some of whom were their own relatives. Of course, some did go, and for very justifiable reasons. Freedom for blacks in early-19th-century America barely warranted the term; they could not vote, serve on juries, nor testify against whites; even the poorest and most ignorant white man could insult, challenge, or even accost a free black man, and there was nothing the latter could do about it. There were positive reasons for going, too. The more evangelical among them believed in the ACS’s mission to spread the Gospel; others anticipated economic opportunities—owning land, starting a business, making money in trade—unavailable to them in the land of their birth.

Along with recruits, the ACS was also able to raise money from liberal evangelical whites in the North, along with Southerners who saw colonization as a way to safeguard slavery. And, beginning with the Elizabeth, sailing out of New York Harbor almost 200 years to the day after the Mayflower set forth from England, the ACS began to dispatch ships.

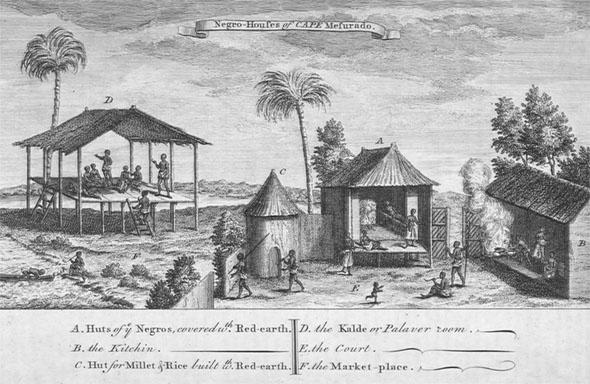

For the early Liberian pioneers, life was, if anything, even tougher than it was for the Pilgrims. They enjoyed no Thanksgiving feast. Food and potable water were in short supply, and the local Africans—ignoring the resemblance the newcomers bore to themselves—proved very unwelcoming. The settlers first put down in Sierra Leone, London’s own sanctuary for free blacks and freed slaves. But conditions there were miserable and the British unwelcoming, so representatives of the ACS and the U.S. Navy “negotiated” with the natives for Cape Mesurado (where modern-day Monrovia is now located), one of the few sheltered inlets on the Windward Coast.

Public domain

War between native and settler punctuated Liberia’s first century. The native Africans of the coast felt they had been forced at gunpoint to give up Mesurado and they did not like the fact that the fiercely abolitionist settlers kept interfering in the lucrative business of smuggling slaves. (The international trade had been outlawed by America and Britain more than a decade earlier.)

As one settler remarked, “[i]t is something strange to think that these people of Africa are calld [sic] our ancestors … for you may try and distill that principle and belief in them and do all you can for them and they still will be your enemy.” The natives persisted in calling the newcomers “black white men.”

But mostly there was disease. Ebola’s current ravages, awful as they are, pale in relative terms to what the first pioneers faced. Malaria and yellow fever hung over Monrovia, the capital named for ACS supporter and U.S. President James Monroe, and the other settlements like a fog. Moans and groans and the stench of diarrhea emanated from the so-called receptacles, the barracks set up for new arrivals; people wandered the grassy streets in fevered dazes. One historian, calling early Liberia a “charnel house,” estimated it suffered “the highest rate of mortality ever reliably recorded.” Of the nearly 3,000 settlers arriving in the 1830s, more than a third died from one or another tropical plague. More compelling than the numbers was one settler’s comment that Liberian graveyards “always look fresh.”

The ACS bore a significant degree of responsibility for the suffering. Africa’s west coast had a well-deserved reputation as a “white man’s graveyard.” But to sell the idea of colonization, the organization’s recruiters insisted that African Americans had a natural immunity to the local fevers. They did not, and the ACS knew it. Moreover, the society sent émigrés on its own schedule, at least at first, which put them in Liberia at the onset of the rainy season, the worst possible time to arrive.

The grim facts soon got back to America, discouraging free blacks from emigrating. Meanwhile, abolitionists attacked the enterprise. Both black and white freedom fighters called colonization the “humbuggery” of the age, meant to undergird slavery rather than end it, by ridding the South of a community—free blacks—most Southerners deemed a threat to the “peculiar institution.” That, too, led many free blacks to reconsider the whole Liberia enterprise. In their place came increasing numbers of freed slaves, as state legislators across the North and South, reacting to old fears about free blacks, passed increasingly restrictive laws against manumitting slaves, unless they were sent away. By the time the Civil War and emancipation largely dried up the stream of émigrés, freed slaves and their descendants had come to outnumber free blacks in the country.

Meanwhile, other forces were pushing Liberians—at least, those who survived the deadly acclimatizing process—toward independence. Despite its self-proclaimed mission to offer African Americans a chance to shape their own destiny in a new land, the ACS refused to cede decision-making power from white agents to black settlers. The latter, ACS officials in Washington insisted with a condescending paternalism, were simply not ready for self-government. From the beginning the settlers chafed under this order but were forced to accept it because the agents had control over land and supplies.

But as the ACS weakened at home—as its middle-of-the-road position on the slavery question grew untenable in politically polarized pre-Civil War America and donations stopped coming in—it lost its power of the purse strings. In a series of reforms, it offered increasing self-rule to the settlers. That, however, was not enough for the firebrands, who, in 1847, declared themselves independent, becoming the world’s second black republic, after star-crossed Haiti.

Liberia’s Declaration of Independence was modeled after America’s, but with a preamble uniquely its own. “We the people of Liberia were originally inhabitants of the United States of North America. … We were excluded from all participation in the government. We were taxed without our consent. … In coming to the shores of Africa, we indulged the pleasing hope we would be permitted to exercise and improve those faculties which impart to man his dignity … to evince to all who despise, ridicule and oppress our race that we possess with them a common nature.”

Stirring words by any measure, except inclusiveness. Where were the 95 percent of Liberians who had never been “inhabitants of the United States”? Like the ACS before it, the new settler government decided the vast majority of native Africans were not ready for self-rule. Besides, giving them the vote would overwhelm the tiny settler numbers. So Liberia’s founding fathers created a republic but kept it for themselves, much like their former masters had done back in 1776. The omission would haunt the republic for the rest of its days.

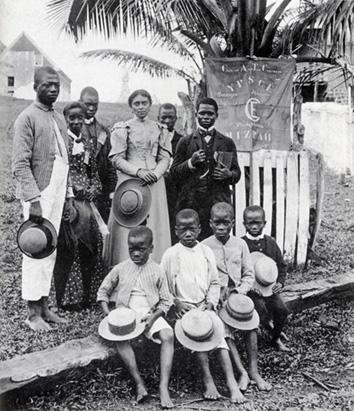

Photo by Apic/Getty Images

And it was not just the pioneers’ flawed democracy that eerily echoed the only culture they were familiar with—that of antebellum America. The Americo-Liberians, as they came to call themselves, built one-room schoolhouses and clapboard churches. They put on frock coats and petticoated dresses, and cooked up the foods they knew from home. A fortunate few even set up plantations on the frontier where, from the columned porches of their manses, they issued orders to the natives tilling their tobacco, coffee, and cotton fields.

They never exactly thrived—the country remained poor and constantly in debt to outsiders—but they did survive, a not insignificant accomplishment in an era when Europeans, periodically clawing off chunks of the country’s coast and hinterland, had abrogated to themselves the right to rule over every dark-skinned person on Earth. The Americoes did it through agile diplomacy and, when things got really desperate, appeals to their American big brother, which usually did nothing beyond sending a sternly worded diplomatic note to London or Paris.

A forgotten backwater—frozen in time—Liberia suddenly came to life after World War II. An automobile-hungry world could not get enough of the country’s iron ore deposits and plantation-grown rubber. For the first time, Liberia knew real prosperity, and established something of a middle class. These were the decades of fancy debutante balls at the Ducor Hotel, summer vacations in Europe, and secret conclaves at the grand Masonic Temple—the largest in Africa, where the real business of government occurred.

Photo by AFP/Getty Images

Presiding over it all was the diminutive, cigar-chomping William Tubman, the grandson of Georgia slaves, the original African big man. President-for-life, even if he kept up appearances by running every four years, Tubman was a brutal autocrat—he set up no fewer than six different security services—but an inclusive modernizer as well. He integrated the native masses into the republic, such as it was, and sent them to school. Thousands went abroad on scholarships, mostly to the United States, where they studied law and earned engineering degrees. And, after a fashion, Tubman foresaw the future. “I’m committing political suicide,” he once said, half-jokingly. “These boys will come back experts, and I know nothing but the Bible.”

In the decade after he died in 1971, Liberia found itself increasingly torn by political factionalism. The old Americo-Liberian guard was not ready to give up power and influence to an increasingly restive native majority, schooled in black-power rhetoric from their days in America and witnesses to the liberation movements sweeping their continent. Liberia, to them, was an anachronism and an embarrassment, with its insulting pioneer-centric culture—a prominent holiday featured re-enactments of settlers massacring natives—and slavish Americanism. They organized new political parties and held anti-government rallies. One, in April 1979, to protest hikes in the price of rice, degenerated into mass rioting and a police massacre.

Photo by Frank Hall via Wikimedia Commons

But it wasn’t the new native intellectuals who brought the ancien régime to an end, it was a more elemental force—the much-put-upon native enlisted men of the armed forces of Liberia. On April 12, 1980, more than a dozen of them, led by a sinewy young master sergeant named Samuel Doe, broke into the Executive Mansion and murdered William Tolbert—Tubman’s successor and the last in a 130-year line of Americo presidents—in his bedroom. The people danced in the streets. After a series of kangaroo court trials, 13 members of the Tolbert government were tied to telephone poles on a Monrovia beach and summarily executed. As one jubilant eyewitness told a New York Times reporter, the men had “no right to live” after all those years “killing our people and stealing our money.”

Photo by Pascal Guyot/AFP/Getty Images

Barely literate himself, Doe brought in the radical intellectuals to run the government. But they soon had a falling out with the soldiers who held the real power. As autocratic as Tubman, Doe lacked the old man’s political skills; the main thing that kept him in power was lavish Cold War military aid from the Reagan administration. Finally, after a decade of repression and economic chaos, a new figure appeared on the horizon. Charles Taylor, the megalomaniacal son of an Americo judge and Gola mother, raised a rebel army—including, eventually, thousands of child soldiers—and unleashed it against Doe, who was soon executed by yet another warlord.

For the next 14 years—aside from a brief hiatus of troubled peace in the late 1990s—Liberia was torn by a civil war so brutal it beggars the imagination: teenagers forced to kill their parents to prove allegiance to this warlord or that, once-respected elders ordered by soldiers young enough to be their grandchildren to “give me six feet,” meaning dig their own graves. On my visits to Liberia in the late 1990s, I interviewed nearly 100 people; I rarely met anyone who had not personally witnessed a murder, often of a loved one.

Photo by Joel Robine/AFP/Getty Images

Exhausted and traumatized, Liberians finally found peace, and then competent government under the grandmotherly “iron lady,” Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, whose Nobel Prize Peace Prize in 2011 testified to her commitment to building a new and more inclusive democracy in Liberia. Slowly, the country was beginning to rebuild itself, heal old wounds.

And now this—a mass epidemic of a most terrifying disease that appears to have no end in sight. International health officials predict that, even with America’s aid, the disease is likely to infect tens of thousands of Liberians in the coming weeks and months. We cannot do enough for Liberia—our African stepchild—in its moment of need. Pioneers from America settled Liberia and established it as Africa’s first republic; they modeled its institutions after our own. If we are true to our values and obligations, we will not abandon Liberia again once the current crisis has passed.

Our government has earmarked an unprecedented sum to reverse the epidemic in Liberia and its neighbors. But as Americans, we can and should give as individuals. There are any number of organizations doing sterling work in fighting Ebola and aiding its victims—Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, Global Health Ministries. Find one online and send it money now. We owe nothing less to the people of Liberia, descendants of both those who came from our shores and those who met them on the shores of Africa so many years ago.