Excerpted from In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette by Hampton Sides, out Aug. 5 from Doubleday.

Close to midnight on the evening of Sunday, Nov. 8, 1874, as the early edition of the next day’s New York Herald was being born, the gas-lit building at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street bustled. The telegraph machines hammered away, the press platens churned, the setting room clinked with the frenetic rearranging of metal movable type, the copy editors clamored for last-minute changes—and outside, in the cool autumn air, the crews of deliverymen pulled up to the freight docks with their dray horses and wagons waiting to load the hemp-tied bundles and carry them to every precinct of the slumbering city.

Following routine, the night editor had the draft edition of the paper brought up to the publisher for his approval. This was no mean feat: The proprietor of the New York Herald could be a tyrannical micro-manager, and he wielded his blue pencil like a Bowie knife, often scribbling barely legible comments that trailed along the margins and then off the page. After his usual wine-drenched dinner at Delmonico’s, he would return to his office to drink pots of coffee and torment his staff until the paper was finally put to bed. The editors dreaded his tirades, and expected him to demand, well into the wee hours, that they rip up the entire layout and start over again.

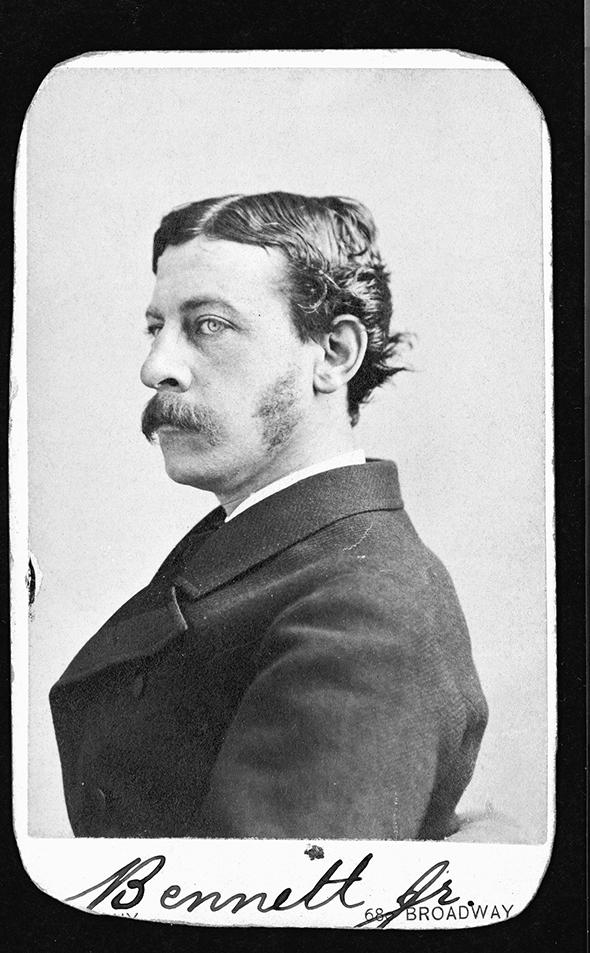

James Gordon Bennett, Jr., was a tall, thin, regal man of 32 years, with a trim mustache and fine tapering hands. His blue-gray eyes seemed cold and imperious, yet also carried glints of mischief. He wore impeccable French suits and dress shoes of supple Italian leather. To facilitate his long if erratic work hours, he kept a bed in his penthouse office, where he liked to snatch an early morning nap.

By most reckonings, Bennett was the third richest man in New York City, with an assured annual income just behind that of William B. Astor and Cornelius Vanderbilt. Bennett was not only the publisher but also the editor in chief and sole owner of the Herald, probably the largest and most influential newspaper in the world. The Herald had a reputation for being as entertaining as it was informative, its pages suffused with its owner’s sly sense of humor. But its pages were also packed with news; Bennett outspent all other papers to get the latest reports via telegraph and the trans-Atlantic cable. For the newspaper’s longer feature stories, Bennett did whatever was necessary to acquire the talents of the preeminent names in American letters—writers like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, and Walt Whitman.

Bennett was also one of New York’s more flamboyant bachelors, known for affairs with burlesque stars and drunken sprees in Newport. He was a member of the Union Club and an avid sportsman. Eight years earlier, he had won the first trans-Atlantic yacht race. He would play an instrumental role in bringing the sport of polo to the United States, as well as competitive bicycling and competitive ballooning. In 1871, at the age of twenty-nine, Bennett had become the youngest commodore in the history of the New York Yacht Club—a post he still held.

The Commodore, as everyone called Bennett, was known for racing fleet horses as well as sleek boats: Late at night, sometimes fueled with brandy, he would take out his four-in-hand carriage and careen wild-eyed down the moonlit turnpikes around Manhattan. Alert bystanders tended to be both puzzled and shocked by these nocturnal escapades, for Bennett nearly always raced in the nude.

* * *

Gordon Bennett’s most original contribution to modern journalism could be found in his notion that a newspaper should not merely report stories; it should create them. Editors should not only cover the news, he felt, they should orchestrate large-scale public dramas that stirred emotions and got people talking. As one historian of American journalism later put it, Bennett had the “ability to seize upon dormant situations and bring them to life.” It was Bennett who, five years earlier, had sent Henry Stanley to find the missionary-explorer David Livingstone in remote Africa. Never mind that Livingstone did not exactly need finding. The dispatches Stanley sent back to the Herald in 1871 had caused an international sensation—one that Bennett was forever seeking to recreate.

Critics scoffed that these exclusives were merely “stunts,” and perhaps they were. But Bennett had a conviction that a first-rate reporter, if turned loose on the world to pursue some human mystery, or solve some geographical puzzle, would invariably come back with interesting stories that would sell papers and extend knowledge at the same time. Bennett was willing to spend profligately to get these kinds of stories into his paper on a routine basis. His paper was many things, but it was rarely dull.

Courtesy of Stanford University Newspaper Archives

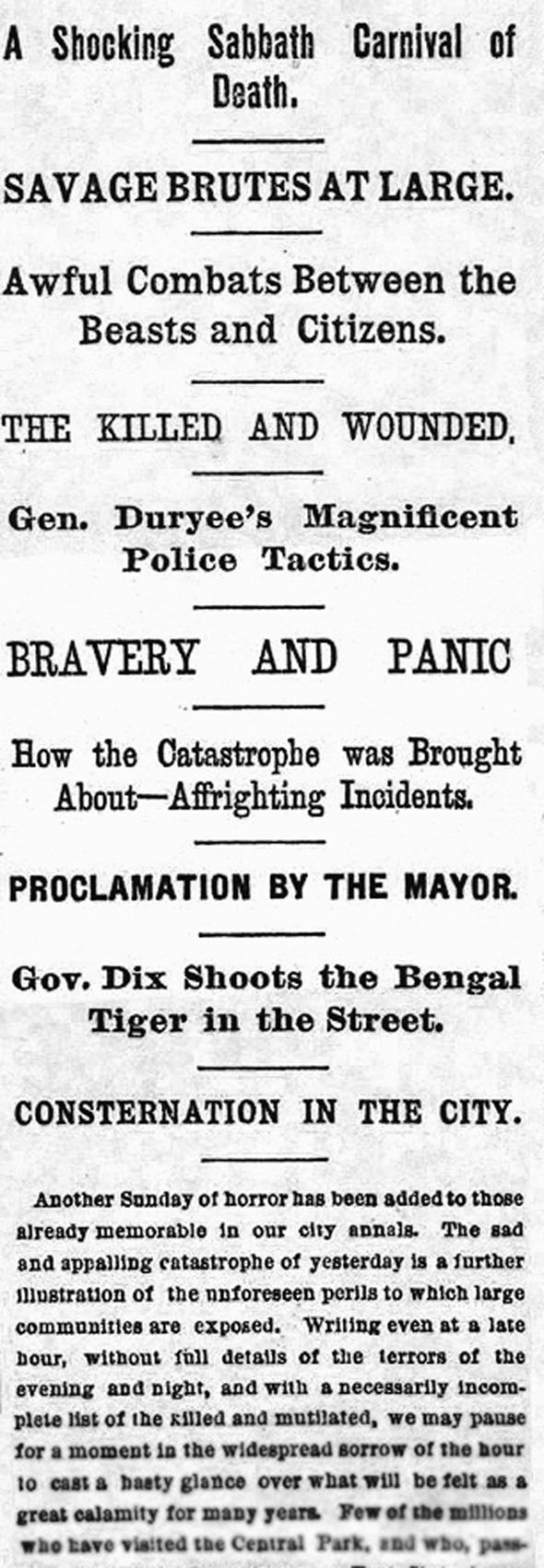

Now, on this early November morning, the Herald’s night editor must have been cringing as he had the still-warm draft of the first edition sent to his mercurial boss. The Herald contained a lead story that, if executed properly, was guaranteed to cause the kind of stir that Gordon Bennett delighted in. It was one of the most incredible and tragic news exclusives that had ever run in the Herald’s pages. The story was headlined, “A Shocking Sabbath Carnival of Death.”

The Commodore scanned the paper and began to take in the horrifying details: Late that Sunday afternoon, right around closing time at the zoo in the middle of Central Park, a rhinoceros had managed to escape from its cage. It had then rampaged through the grounds, killing one of its keepers—goring him almost beyond recognition. Other zookeepers, who had been in the midst of feeding the animals, rushed to the scene, and somehow in the confusion, a succession of carnivorous beasts—including a polar bear, a panther, a Numidian lion, several hyenas, and a Bengal tiger—had slipped from their pens. What happened next made for difficult reading. The animals, some of which had first attacked each other, then turned on nearby pedestrians who happened to be strolling through Central Park. People had been trampled, mauled, dismembered—and worse.

The Herald reporters had diligently captured every detail: How the panther was seen crouching over a man’s body, “gnawing horribly at his head.” How the African lioness, after “saturating herself in the blood” of several victims, had been shot by a party of Swedish immigrants. How the rhino had killed a sewing girl named Annie Thomas and then had run north, only to stumble to its death in the bowels of a deep sewer excavation. How the polar bear had maimed and killed two men before tramping off toward Central Park’s upper reservoir. How, at Bellevue Hospital, the doctors were “kept busy dressing the fearful wounds” and found it “necessary to perform a number of amputations. … One young girl is said to have died under the knife.”

At press time, many of the escaped animals were still at large, prompting Mayor William Havemeyer to issue a proclamation that called for a rigid curfew until “the peril” had subsided. “The hospitals are full of the wounded,” the Herald reported. “The park, from end to end, is marked with injury, and in its artificial forests the wild beasts lurk, to pounce at any moment on the unwary pedestrians.”

Bennett did not break out his blue pencil. For once, he had no changes to suggest. He is said to have simply leaned back amongst his pillows and “groaned” at this remarkable story.

* * *

The Herald report was written in an even tone. Its authors peppered it with intimate details and filled the printed roster of the victims with the names of actual, in some cases quite prominent, New Yorkers. But the story was entirely a hoax. With Bennett’s enthusiastic encouragement, the editors had concocted the tale to illustrate that the city had no evacuation plan in the event of a large-scale emergency—and also to point out that, in fact, many of the cages at the Zoo were flimsy and in bad need of repair. The outmoded Central Park menagerie, the editors later noted, was a far cry from the state-of-the-art zoo at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. It was time for New York City to rise to the level of a world-class city, and for the nation, whose one-hundredth birthday was approaching in just over a year and a half, to have at least one world-class park to display the planet’s wildest creatures.

Lest anyone say that the Herald had deceived its readers, the editors had, in fact, covered their bases. Anyone who read “A Shocking Sabbath Carnival of Death” to its end (buried discreetly in the back pages) would have found the following disclaimer: “Of course, the entire story given above is a pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true.” Still, the paper contended, the city fathers had given no thought to what might happen in an authentic emergency. “How is New York prepared to meet such a catastrophe?” the Herald asked. “From causes quite as insignificant the greatest calamities of history have sprung.”

Bennett knew from experience that very few New Yorkers would bother to read the article all the way to its conclusion, and he was right: That morning, as the usual clouds of anthracite coal fumes began to rise over the stirring city, people turned to their morning papers—and were plunged in chaos and confusion. Alarmed citizens made for the city’s piers in hopes of escaping by small boat or ferry. Many thousands of people, heeding the mayor’s “proclamation,” stayed inside all day, awaiting word that the crisis had passed. Still others loaded their rifles and marched into the park to hunt for rogue animals.

It should have been immediately apparent to even the most naive reader that the piece was a spoof. But this was a more credulous era, a time before radio and telephones and rapid transit, when city dwellers got their information mainly from the papers and often found it hard to tease rumor from truth.

Later editions took the story even further: Now the Herald reported that the governor of New York himself, a Civil War hero named John Adams Dix, had marched into the streets and shot down the Bengal tiger as a personal trophy. A much-expanded list of animals had escaped from the zoo, including a tapir, an anaconda, a wallaby, a gazelle, two Capuchin monkeys, a white-haired porcupine, and four Syrian sheep. A grizzly bear had entered the Church of St. Thomas on Fifth Avenue, and there, in the center aisle, it “sprang upon the shoulders of an aged lady, and buried his fangs in her neck.”

The editors of rival newspapers were thoroughly perplexed. It was not the first time the Herald had scooped them, but why had their reporters failed to glean even an inkling of this obviously momentous event? The city editor of the New York Times stormed over to police headquarters on Mulberry Street to scold the department for feeding the story to the Herald while ignoring his esteemed paper. Even some staffers of the Herald fell for the prank: One of Bennett’s most celebrated war correspondents, who apparently had not gotten the memo, showed up at the office that morning armed with two big revolvers, ready to prowl the streets.

Predictably, Bennett’s rivals excoriated the Herald for its irresponsible conduct—and for spreading widespread panic that could have resulted in loss of life. A Times editorial observed: “No such carefully prepared story could appear without the consent of the proprietor or editor—supposing that this strange newspaper has an editor, which seems rather a violent stretch of the imagination.”

Such expressions of righteous indignation fell on deaf ears. The Wild Animal Hoax, as it came to be affectionately known, only brought more readers to the Herald. It seemed to solidify the notion that Bennett had his finger on the pulse of his city—and that his daily journal had a sense of fun. “The incident helped rather than hurt the paper,” one historian of New York journalism later noted. “It had given the town something to talk about and jarred it as it had never been jarred before. The public seemed to like the joke.”

Bennett was enormously pleased with the whole affair—it still ranks as one of the great newspaper hoaxes of all time. The story even managed to accomplish its ostensible goal: The zoo’s cages were in fact repaired.

Copyright 2014 by Hampton Sides. From In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette, to be published by Doubleday on Aug. 5. Reprinted with permission.