Most commentary on the Supreme Court’s Harris decision has emphasized the ruling’s limited nature: While public-sector unions can no longer collect certain administrative fees, the decision could have been much broader, and much more damaging to organized labor.

But there is another, more important decision that still needs to be made when it comes to unions, and this one will happen mostly outside of the courts. Unless something dramatic changes, Americans are on the verge of living in a nation where the right to organize and to belong to a labor union no longer exists. The country will need to decide, sooner rather than later, if those rights are worth preserving.

At the moment, fewer than 7 percent of private-sector workers belong to unions, and that number continues to shrink. (In the public sector, numbers are somewhat higher, but unlikely to grow.) This is approximately the same percentage of workers who belonged to private-sector unions at the turn of the last century, at the height of the Gilded Age.

Not coincidentally, both eras also witnessed soaring inequality, with the top corporate earners absorbing ever-increasing shares of the nation’s wealth. Economists point to many factors to explain this circumstance, from globalization to changes in regulatory infrastructure. From the perspective of a political historian, though, there is also a simpler story to tell. Unions have long played a key role in constraining inequality, and in giving the working and middle classes a counterweight to the outsize political influence of the 1 percent. Historically speaking, the fate of organized labor and the fate of the American dream have gone hand in hand.

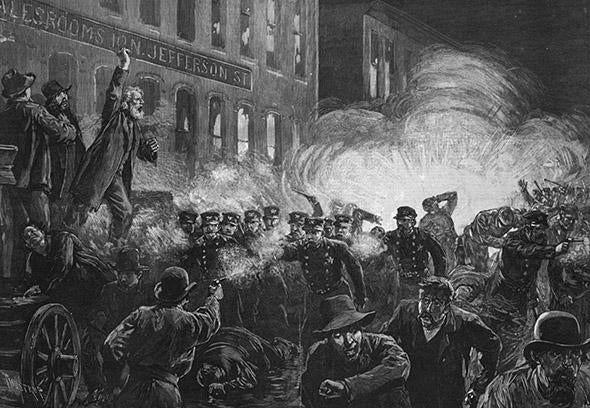

There were glimmers of union organizing even before the Civil War, but the modern labor movement began in earnest in the 1870s, with the rise of mass industry and large corporations. From there, it took more than 60 years to win federal recognition of the right to organize. The turning point came in 1935 with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (better known as the Wagner Act), the law that still governs most organizing efforts in the United States today. Union membership peaked in the mid-1950s at about 35 percent of private-sector workers, and has been falling ever since.

It is no coincidence that the labor movement’s glory days also yielded the building blocks of the social welfare state, including Social Security and overtime laws. There were many reasons for these developments, including Cold War image pressure: If you wanted to compete with the Soviets as the world’s model society, it was unseemly to concentrate too much wealth at the top. But unions played a key role in pushing for these changes at a national level, as well as securing wages that helped to even out the divide between executives and their employees. The middle decades of the 20th century are the only time in modern American history when inequality actually decreased, and Americans began to play more and work less. You’ve probably seen the union bumper stickers: “From the folks who brought you the weekend.” That slogan reflects a basic historical truth.

Public-sector unions had their own brief heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, when teachers and government clerks and air traffic controllers made a push for recognition. That momentum came to an abrupt halt in 1981, when Ronald Reagan fired the entire membership of the striking PATCO union. In the decades since, despite periodic bursts of organizing success, public-sector unions have barely held their own, while private-sector numbers have continued to plummet. All the same, according to the latest Pew Research Center poll, a majority of Americans continue to hold a favorable view of unions, and to see them as important protections for the working class.

Today, as labor historian Joseph McCartin has pointed out, the few unions that remain have all but given up on what was once their most potent weapon: the right to strike. In 1952, a fairly typical year in labor’s heyday, more than 2 million workers went out on strike. By 2002, just 46,000 workers engaged in that kind of action, and the numbers have fallen still further since. In 2009, the worst year of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, just 13,000 workers went on strike, in only five separate work stoppages. There was no shortage of economic complaint or suffering, just a shortage of organized action.

For consumers, this might be seen as a welcome development: The trains keep running, the schools stay open, the mail gets delivered. For anyone who cares about inequality, however, the near disappearance of American unions—even of strikes—should be cause for concern. At the moment, we seem to be awash in well-intentioned and even visionary policy proposals to stem the tide of inequality, from Thomas Piketty’s global wealth tax to President Obama’s call to raise the minimum wage. What’s missing from the conversation is how, exactly, any of this is going to happen, absent some sort of serious organized pressure from below. That’s what unions have always provided: the on-the-ground “how” to the pie-in-the-sky “what.”

It is possible that the 21st century will yield other alternatives for this sort of organized economic effort—new forms of online petitioning or philanthropy or communication that will put all of the old questions to rest. From a historical perspective, though, the prospects look dim. Today’s Supreme Court may have issued a narrow decision but it raised a large question: Do Americans want unions to exist anymore? If so, there’s some serious work to do.