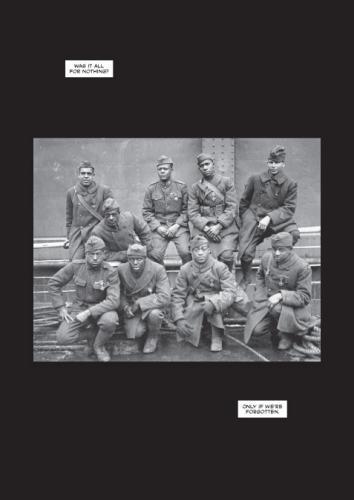

In the just-released The Harlem Hellfighters, Max Brooks—who made his name with the The Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z—dives into the story and heroics of the 369th U.S. Army Infantry Regiment, the all-black unit assembled to fight in World War I.

After facing intense discrimination and racist treatment at the hands of their superiors, the soldiers were sent to join the French Army on the Western Front, where they became one of the most decorated units of the war effort. It was their willingness to take dangerous assignments—and their refusal to concede an inch of ground—that earned them the “Hellfighters” moniker from German soldiers.

Illustrated by Caanan White (who also draws Uber, a World War II comic), the book represents several decades of historical interest from the 41-year-old Brooks, who is the son of Mel Brooks and the late Anne Bancroft. I spoke with him earlier this week about the book, its origins, and the history behind it. This is the full interview, edited for clarity.

What was the genesis of this project?

The idea came from a guy named Michael Furmanovsky who worked for my parents when I was a kid. He was a personal assistant doing odd jobs and errands while putting himself through school to become a history professor. He learned about [the 369th infantry regiment] while researching a Marcus Garvey project for UCLA. And he just told me about them in one sentence, but I never forgot about it.

Over time, I learned more about them and became entranced by their combat record. And I learned obviously about the context of how African Americans were treated in the military. For an African American unit to overcome racism and make a contribution to the war effort would have been heroic enough. But to actually make a difference is truly what they mean when they say “above and beyond.”

Absolutely. It was incredible to read how successful they were in their fighting across the Western Front.

If this had been a white unit, we would be doing God knows how many remakes of the movies about them. And race aside, this was an important unit for the war effort, and that should be celebrated, not just the fact that they encountered racism.

One thing that has always struck me about the First World War is how little Americans know about it. It’s opaque and impenetrable to a lot of people. Racism aside, do you think that this is part of the reason this kind of story hasn’t been told?

Courtesy of Caanan White and Random House

I think World War I has been largely overshadowed by World War II. You don’t have to be a warmonger to appreciate the struggles of the Second World War. Fighting Hitler—who’s not going to get behind that? Avenging Pearl Harbor—how is that controversial?

It also was a more visually fascinating war. You can picture fleets of warships and columns of tanks and airplanes so thick they blot out the sun. You know, this war of mobility, this war of mechanization. Whereas World War I was just young men shivering and dying in muddy trenches, and literally not moving an inch for four years. Not only was it a static war, not only was it a brutal war—it was a stupid war. What was it about?

The great powers of Europe kind of just stumbled into it and fell ass-backwards into the apocalypse. I think that’s why World War I is not the stuff of legends, whereas World War II can be Lord of the Rings, but with tanks.

To get back to the story itself, one of the things I liked about your treatment of the racism of the era is that you alluded to the waves of anti-black violence that struck throughout that decade. Most people understand that there was violence against individuals and families, but not this organized violence against entire towns.

I think the closest thing we can come to imagining something like that [violence] is when we watch a zombie outbreak movie, and we see people fleeing for their lives from carnivorous hordes trying to wipe them out. That is literally what happened to black people in the last century, when there were these horrific race riots. And when we think about race riots, we tend to think about Rodney King—unruly black people burning down their own stores. That totally was not the case. These were lynch mobs and violence against civilians.

What struck me in the story was the degree to which their white American superiors tried to sabotage them.

What I didn’t expect is that when they sent them to Spartanburg [in South Carolina], it was two weeks after the worst race riot in history, in Houston. The mayor of Spartanburg had written to the army and said, “Do not send them here.” And he said, “Remember what happened in Houston? If you send them here, there’s going to be trouble.” The fact that the U.S. Army still sent them there, I don’t think it was a mistake. I think it was intentional.

Courtesy of Jacqui Howell

All of this puts the post-war violence against black soldiers into better perspective.

I think it’s really important to understand why that backlash happened. I truly believe the U.S. government went out of its way to sabotage these guys specifically because it didn’t want [black] heroes coming home. You remember the movie Glory that came out in the 80s? Well, the 54th Massachusetts—they all died trying to take a fort that was never taken. I think that’s the kind of end the U.S. government hoped for with the Harlem Hellfighters. Their worst fear was these guys coming back with their medals telling war stories about how they saved democracy.

Another point worth making is that the First World War was the first time you saw large amounts of black officers. You know, there had been black soldiers in every war, and there had been black officers. But there had never been that many of them and they were never so visible. And that, I think, scared the crap out of the white status quo.

We have this tradition of our war heroes coming home and running for public office. Well, what the hell would it have meant for the status quo if you had a large number of young, very well-educated black men coming home with medals on their chest who had learned how to lead men in combat. It’s a nightmare.

On a different note, I thought Caanan did a great job of depicting trench warfare. There were a couple scenes that were tough just to look at. It was graphic, in a good way. Not gratuitous, but realistic.

Courtesy of Caanan White and Random House

We made sure that every act of violence committed in this story was based on actual research, so we could never be accused of being gratuitous. Caanan drew a picture of a man being blown apart by a high explosive shell. He’s literally bursting like a water balloon. Well, that is exactly what I read about while I was doing research for this book. The explosive force of the shell—the energy, not the shrapnel—the actual energy is absorbed by the water in your body that creates a shockwave that bursts you like a balloon.

Depicting that kind of violence is really important. I don’t think war should be sanitized. It shouldn’t be exciting and cool. It should be graphic and horrible, and I think you should flinch when you see it.

How did your collaboration with Caanan White come about?

He was working on a really successful World War II comic called Uber, and I fell in love with Caanan’s work for two things. First, he can draw war. I read a ton of war comics and in some of them I find mistakes that are just unforgivable. You have guys grabbing guns by handles that are not there, things like that.

He can also draw detail, and that’s really important when you do any kind of historical comic book. When you’re doing a comic book about the modern era—we all know what that looks like. When you’re doing something historical, you’re educating with your pictures. It’s a really tough job, and Caanan’s job was even tougher because he had to draw real people. He’s a rock star.

You know, I’d love to see this as a movie.

Well, my next project is that I’ll be writing the screenplay of the movie for Sony Pictures and Will Smith. I don’t know if the movie is even going to get made, but we are at the very early stages of the process.

For example, I’m not upset that Ted Nugent called the president of the United States a “sub-human mongrel,” because Ted Nugent is an animal. He’s no more responsible for what he says than when my dog barks. The problem is that the Republican Party didn’t immediately distance itself from him. The fact that there are still politicians who recruit him to their campaigns—that shows we still have a problem.