Kim Hopfer, a mother of two, lives on a farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. She works as a truck driver, and each year spends her one week of vacation re-enacting the Civil War—not in a hoop skirt and bonnet, knitting socks, but in a pair of Union blue trousers, among the ranks of the 138th Pennsylvania. The re-enacting community often derides wannabe re-enactors whose personas are historically inaccurate as “farbish,” but in fact Kim is far from farbish. She represents one of as many as a thousand women who served in the Union and Confederate armies during the war, cross-dressed as men.

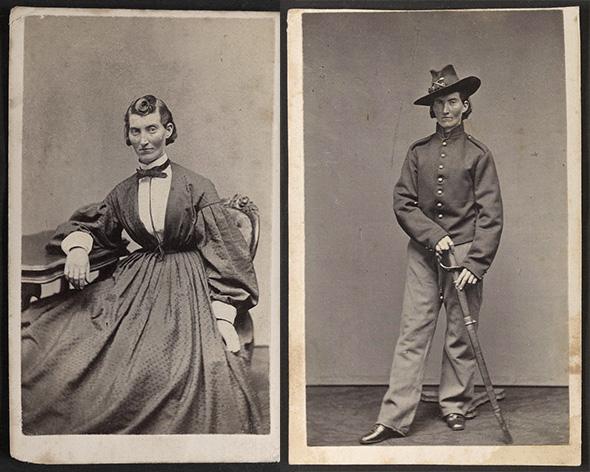

One of these soldiers was Frances Louisa Clayton, alias Jack Williams, a Minnesotan who enlisted with her husband in 1861. To pass as one of the boys, she took up drinking, smoking, chewing, and swearing. When Frances’ husband died, a few feet in front of her at Stones River, she stepped over his body and kept fighting. Many like Frances enlisted with loved ones; a woman from Tennessee named Melverina Elverina Peppercorn joined the Confederate army to be with her brother. At least two women went to war with their fathers.

But women also enlisted for many of the same reasons soldiers enlist today: patriotism and adventure, honor, economics. (A maid in New York at the time could earn $4 to $7 a month for her services; a Union soldier got $13 a month.) The war ignited the imaginations and ambitions of young women like Emily, a 19-year-old from Brooklyn who wanted to enlist because she believed she was Joan of Arc reincarnate. Harriet Merill joined the 59th New York Infantry in order to leave behind the brothel where she worked.

Last summer, I met Kim Hopfer at the 150th anniversary re-enactment of the Battle of Gettysburg. She is a tall, stately woman, who was wearing wool trousers and a long-sleeved checked shirt in spite of the 80-degree heat. Round metal (period-appropriate) glasses framed her soft, gentle face, and she immediately apologized for talking to me with a mouthful of beef jerky.

Photo courtesy of Kim Hopfer

“That only adds to the realism,” I assured her.

“I’m sorry, I just took a big piece.”

When I asked Kim about her impression (the preferred term for a re-enactor’s persona; they don’t like to be asked about their “character” or who they’re “playing”), she told me she was a soldier in the 138th Pennsylvania, a volunteer infantry unit organized here in Gettysburg. During the Civil War, one notable member of the 138th was Peter Thorn, the caretaker of Evergreen Cemetery, where some of the actual battle took place, and where President Lincoln eventually delivered his Gettysburg Address.

But the 138th missed all the action at home. They were at Harper’s Ferry in June, and on their way to Washington in early July.

“We found out while we were there that the battle here, in our hometown, was going on. So, you know: panic. We’re not able to be here to defend our own hometown, so it was pretty traumatic,” Kim told me, speaking in the first-person plural about an event that occurred 150 years ago.

Although she lives in town, this was her first time re-enacting at Gettysburg, and she was still trying to adjust to the heat. “You got to march, you got to keep time, you have all these clothes on, you have a 12-pound rifle plus however much weight in gear, plus all the wool that you have on.” Raising her boot for me to have a look, Kim said, “These are the most uncomfortable things I’ve ever had on my feet. They’re very hard. They’re very flat.” She admitted that she and some of her comrades “kind of have a Dr. Scholls thing going on in there” to make it a bit more comfortable. “Your feet hurt. Your back hurts. Your shoulder hurts. Your arms hurt. But it’s worth it. It’s really worth it.”

When I asked what made her want to portray a soldier, Kim told me she believed she was born in the wrong time period. “This is my time period. Because if my son or my husband was out there, I would have done the same thing. I would have cut my hair. I would have followed them into battle. I’m a big girl, but I would have wrapped and hid and done whatever I had to do in order to get out there.”

Many did wrap and hide and do whatever they had to do. At least five women fought in the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, including an unidentified drummer girl who swore that once she healed from her injuries she would never wear a dress again.

In the mid-19th century, no one carried an ID card. To enlist, a woman basically needed only to cut off her hair and pick an alias. Army surgeons conducting physical examinations often checked only to see if a recruit had teeth to tear open powder cartridges and a finger to pull a trigger. Once she enlisted, however, a female soldier had to learn to pass as one of the boys. Loreta Velazquez sometimes wore a fake mustache. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, a farm girl from New York who served as Pvt. Lyons Wakeman, wrote home to brag of a fight in which she gave another private in her regiment “three or four pretty good cracks.” Summing up this kind of identity and gender performance, Sarah Emma Edmonds, a Canadian who served as a Union soldier, nurse, and spy under the alias Frank Thompson, wrote in her memoir that the war was a time for “entire self-forgetfulness.”

While I was at Gettysburg, I also met J.R. Hardman, a 27-year-old filmmaker who is currently making a documentary called Reenactress, about her experiences as a cross-dressing soldier. In addition to firing artillery with the 6th New York, she also switch-hits in gray and re-enacts as an infantry soldier with the 53rd Georgia. Her film will chronicle her experiences on both sides of the Mason-Dixon divide.

Photo courtesy O.K. Keyes.

A hundred and fifty years ago, J.R. would have made a fine recruit. She is tall and slender, with a long boyish neck and short, auburn hair. The previous year, while she was at the 149th anniversary of Gettysburg as a spectator, the captain of the 6th New York recruited J.R. for his unit based on the way she looked wearing a man’s cap.

This year, I sat with the 6th New York while they ate lunch, and that captain, Jeff, was eager to tell me his favorite J.R. story. “We’re at Lambertville,” he started.

“Peddler’s Village!” she corrected.

“Peddler’s Village, sorry. And J.R. was paid the highest compliment a female re-enactor passing as a male re-enactor can get. She’s in the women’s room, washing up, and this lady comes out of the stall, takes one look at her, and freaks out. She didn’t know if she was in the wrong stall or if J.R. was in the wrong bathroom.”

This story brought to mind a more famous case of restroom gender-bending. In 1989, a woman named Lauren Cook Burgess was “caught” coming out of the ladies’ room dressed as a field musician during a re-enactment at Antietam National Battlefield Park. The National Park Service, citing “authenticity,” banned her from the re-enactment, and Burgess went on to successfully sue the NPS for sex discrimination. After the suit, she faced a great deal of backlash from the re-enacting community, including hate mail, and hostility from male re-enactors.

“I’ll never forget being on a ten-mile preservation march in the Shenandoah Valley,” she told me over email. “Several young men made disparaging remarks to me (they did not recognize I was a woman; someone pointed me out to them as the woman who had sued the Park Service), and they were cat calling and making rude remarks when I marched by with my unit. Later on in the march I saw these same boys laid out on the side of the road with heat exhaustion, while I continued on with the march, right past them, carrying a full kit and rifle, and fifing with my fife and drum corps. Do you know how much air it takes to play fife?”

J.R. credits Burgess with paving the way for women who want to re-enact in pants. “She won a lawsuit for gender discrimination and I think because of that, at these big national events, I don’t think they can say anything one way or the other. But if you look in the rules and regulations of a lot of re-enacting events, there’s many times a specific section about women re-enactors.”

Item five of the “impression standards” list on the official Gettysburg Anniversary Committee website reads:

Women portraying soldiers in the ranks should make every reasonable effort to hide their gender. Hundreds, if not thousands, of women passed themselves off as men in order to serve as soldiers during the war—on both sides, and we will never know exactly how many did so because their disguises were so good. Honor them. If any Army or event volunteer (as above) determines the female gender at not less than 15 feet, that individual will be asked to leave the field/ranks.

The reason we know today that “hundreds, if not thousands” of women fought as soldiers is due to the scholarship of Lauren Cook Burgess (now Wike), who went on to co-author the definitive book on female soldiers, They Fought like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War. The book takes its title from a letter a male Union soldier sent back home, after watching several Confederate women fall in a bloody battle: “They fought like demons, and we cut them down like dogs.”

“What launched my research was being told by park rangers that they did not want the ‘oddball, or the eccentric and out of place’ portrayed in their living history,” Lauren told me. “In my opinion, women who served as soldiers in the Civil War were anything but ‘oddballs and eccentrics.’ They were patriots just like their male counterparts, and … the confrontation I had with these officials angered me so much that I was determined to right the historical record.” She spent 15 years researching and writing the book, as well as editing the collected letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (the soldier who wrote home to brag about her fistfight). Now, she is hoping to find the time to update her records with new discoveries, and archive her material for an eventual donation to a museum or library.

Referring to the impression standards, J.R. told me, “I think that what they’re getting at is, ‘Don’t go out there with earrings and curly hair, wearing lipstick.’ But it’s also really off-putting to read stuff like that. It makes you feel like they don’t want you here.”

Aside from their positive experiences with the 6th New York and the 53rd Georgia, J.R. and her cinematographer have both faced gender discrimination on the re-enacting battlefield. The argument for discrimination goes something like this: Technically, women weren’t allowed to fight as soldiers 150 years ago and so they shouldn’t be on the re-enactment battlefield today. If you disagree, you’re historically “inauthentic.”

“You’re not allowed to be offended,” J.R. said. “It’s easy for people to discriminate and give you this idea that you’re not supposed to be mad at them. And when you really think about it, it’s kind of crap. They’re still saying something that’s prejudiced or discriminatory, and it’s easier for them to do that because it’s harder for you to argue because it’s ‘inauthentic.’ But re-enacting isn’t actually the Civil War.”

There’s the rub. The women who’d fought in the Union and Confederate armies 150 years ago had the challenge of forsaking their female identities and assimilating into a completely male culture. But female re-enactors today aren’t trying to disappear into the ranks—they’re fighting for recognition as a subculture within a subculture. J.R. wanted to sleep in a canvas tent for four days and fire a cannon. My mom, who was also re-enacting at Gettysburg, wanted to sleep in a hotel and spend her days in a hoop skirt, washing other people’s laundry. To me, their aspirations seemed equally insane, and at the same time equally legit.

“A hobby is about finding people who are like you, and there are people who are like you in every aspect of re-enacting,” J.R. assured me. “If you’re Suzie Homemaker, or if you’re super feminist, or if you’re Suzie-Homemaker-Super-Feminist, there will be somebody like you. You just sometimes have to look a little bit harder.”

Re-enacting will never succeed as an actual re-creation of events; it occupies a fuzzy territory between theater and history, where the question of authenticity remains unresolved. Case in point: On Nov. 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address, dedicating the National Cemetery to “the brave men, living and dead, who struggled here.” This was truthful, as far as he knew, but I keep thinking about that unnamed drummer girl who said she’d never wear a dress again. How surprised she’d be today, to learn that although American women can wear pants and vote and join the military and go through infantry training, they’re now fighting for the right to bring to life stories like her own.

Some of this article originally appeared, in different form, in a two-part series at The Toast.