This story has been expanded into a book, The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth, as well as a podcast miniseries.

Ronald Reagan loved to tell stories. When he ran for president in 1976, many of Reagan’s anecdotes converged on a single point: The welfare state is broken, and I’m the man to fix it. On the trail, the Republican candidate told a tale about a fancy public housing complex with a gym and a swimming pool. There was also someone in California, he’d explain incredulously, who supported herself with food stamps while learning the art of witchcraft. And in stump speech after stump speech, Reagan regaled his supporters with the story of an Illinois woman whose feats of deception were too amazing to be believed.

“In Chicago, they found a woman who holds the record,” the former California governor declared at a campaign rally in January 1976. “She used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans’ benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.” As soon as he quoted that dollar amount, the crowd gasped.

Four decades later, Reagan’s soliloquies on welfare fraud are often remembered as shameless demagoguery. Many accounts report that Reagan coined the term “welfare queen,” and that this woman in Chicago was a fictional character. In 2007, the New York Times’ Paul Krugman wrote that “the bogus story of the Cadillac-driving welfare queen [was] a gross exaggeration of a minor case of welfare fraud.” MSNBC’s Chris Matthews says the whole thing is racist malarkey—a coded reference to black indolence and criminality designed to appeal to working-class whites.

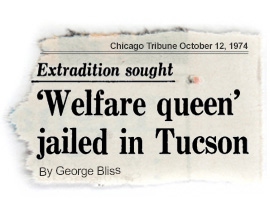

Though Reagan was known to stretch the truth, he did not invent that woman in Chicago. Her name was Linda Taylor, and it was the Chicago Tribune, not the GOP politician, who dubbed her the “welfare queen.” It was the Tribune, too, that lavished attention on Taylor’s jewelry, furs, and Cadillac—all of which were real.

As of 1976, Taylor had yet to be convicted of anything. She was facing charges that she’d bilked the government out of $8,000 using four aliases. When the welfare queen stood trial the next year, reporters packed the courtroom. Rather than try to win sympathy, Taylor seemed to enjoy playing the scofflaw. As witnesses described her brazen pilfering from public coffers, she remained impassive, an unrepentant defendant bedecked in expensive clothes and oversize hats.

Linda Taylor, the haughty thief who drove her Cadillac to the public aid office, was the embodiment of a pernicious stereotype. With her story, Reagan marked millions of America’s poorest people as potential scoundrels and fostered the belief that welfare fraud was a nationwide epidemic that needed to be stamped out. This image of grand and rampant welfare fraud allowed Reagan to sell voters on his cuts to public assistance spending. The “welfare queen” became a convenient villain, a woman everyone could hate. She was a lazy black con artist, unashamed of cadging the money that honest folks worked so hard to earn.

Photo by Constantine Manos/Magnum Photos

After her welfare fraud trial in 1977, Taylor went to prison, and the newspapers moved on to covering the next outlandish villain. When her sentence was up, she changed her name and left Chicago, and the cops who had pursued her in Illinois lost track of her whereabouts. None of the police officers I talked to knew whether she was still alive.

When I set out in search of Linda Taylor, I hoped to find the real story of the woman who played such an outsize role in American politics—who she was, where she came from, and what her life was like before and after she became the national symbol of unearned prosperity. What I found was a woman who destroyed lives, someone far more depraved than even Ronald Reagan could have imagined. In the 1970s alone, Taylor was investigated for homicide, kidnapping, and baby trafficking. The detective who tried desperately to put her away believes she’s responsible for one of Chicago’s most legendary crimes, one that remains unsolved to this day. Welfare fraud was likely the least of the welfare queen’s offenses.

For those who knew her decades ago, Linda Taylor was a terrifying figure. On multiple occasions, I had potential sources tell me they didn’t think I was really a journalist. Maybe I was a cop. Maybe I was trying to kill them. As Lamar Jones tells me about his brief marriage to the welfare queen, he keeps asking how I’ve found him, and why I want to know all of these personal details. If I’m in cahoots with Linda, as he suspects I might be, he assures me that I won’t be able to find him again. He’s just going to disappear.

Those who crossed paths with Linda Taylor believe she’s capable of absolutely anything. They also hope she’s dead.

Jack Sherwin knew he’d seen her before. It was Aug. 8, 1974, and the Chicago burglary detective was working a case on the city’s South Side. Though her name and face didn’t look familiar, Sherwin recognized the victim’s manner, and her story. She’d been robbed, Linda Taylor explained, and she was sorry to report that the burglar had good taste: $14,000 in furs, jewelry, and cash were missing from her apartment. Thank heavens, most of it was insured.

After listening to her tale of woe, Sherwin asked Taylor if she’d mind getting him some water. When she returned, the detective kept the glass as evidence.

Courtesy of Jack Sherwin

The fingerprints collected from Taylor’s kitchen helped jog Sherwin’s memory. Two years earlier, the same woman had been charged with making a bogus robbery claim—that time, the thieves had supposedly made off with $10,000 worth of valuables. Sherwin knew Linda Taylor because, out of pure happenstance, he’d been called on to investigate both of these alleged burglaries. She was living in a different part of town, using a different name, and sporting a different head of hair. But this was the same woman, pulling the same stunt.

Sherwin cited Taylor, again, for making a false report. But the 35-year-old police officer, a former Marine and a 12-year veteran of the force, didn’t stop there. “The more I dug into it, the more I found that just wasn’t right,” he remembers. First, he learned that she was getting welfare checks under multiple names. Then he discovered Taylor’s husbands—“Oh, I guess maybe seven men that I knew of,” Sherwin says. The detective and his partner, Jerry Kush, got to work tracking down this parade of grooms, and they found a few who were willing to talk. Sherwin’s hunch had been right: This woman was up to no good.

In late September 1974, seven weeks after Sherwin met Taylor for the second time, the detective’s findings made the Chicago Tribune. “Linda Taylor received Illinois welfare checks and food stamps, even tho[ugh] she was driving three 1974 autos—a Cadillac, a Lincoln, and a Chevrolet station wagon—claimed to own four South Side buildings, and was about to leave for a vacation in Hawaii,” wrote Pulitzer Prize winner George Bliss. The story detailed a 14-page report that Sherwin had put together illuminating “a lifestyle of false identities that seemed calculated to confuse our computerized, credit-oriented society.” There was evidence that the 47-year-old Taylor had used three Social Security cards, 27 names, 31 addresses, and 25 phone numbers to fuel her mischief, not to mention 30 different wigs.

As the Tribune and other outlets stayed on the story, those figures continued to rise. Reporters noted that Linda Taylor had used as many as 80 names, and that she’d received at least $150,000—in illicit welfare cash, the numbers that Ronald Reagan would cite on the campaign trail in 1976. (Though she used dozens of different identities, I’ve chosen to call her Linda Taylor in this story, as it’s how the public came to know her at the height of her infamy.) Taylor also gained a reputation as a master of disguise. "She is black, but is able to pass herself off as Spanish, Filipino, white, and black," the executive director of Illinois’ Legislative Advisory Committee on Public Aid told the Associated Press in November 1974. "And it appears she can be any age she wishes, from the early 20s to the early 50s.”

For Bliss and the Tribune, the scandal wasn’t just that Taylor had her hand in the till and had the seeming ability to shape-shift. The newspaper also directed its ire at the sclerotic bureaucracy that allowed her schemes to flourish. Bliss had been reporting on waste, fraud, and mismanagement in the Illinois Department of Public Aid for a long time prior to Taylor’s emergence. His stories—on doctors who billed Medicaid for fictitious procedures and overworked caseworkers who failed to purge ineligible recipients from the welfare rolls—showed an agency in disarray. That disarray didn’t make for an engaging read, though: “State orders probe of Medicaid” is not a headline that provokes shock and anger. Then the welfare queen came along and dressed the scandal up in a fur coat. This was a crime that people could comprehend, and Linda Taylor was the perfectly unsympathetic figure for outraged citizens to point a finger at.

Photo illustration by Holly Allen

Now that the Tribune had found the central character in this ongoing welfare drama, a story about large, dysfunctional institutions became a lot more personal. The failure—or worse, unwillingness—to ferret out Taylor’s dirty deeds revealed more about the flaws of state and county government than any balance sheet ever could. In his report to his superiors at the Chicago Police Department, Sherwin described ping-ponging from the Department of Public Aid to the state’s attorney’s office to the U.S. attorney, with none of the agencies expressing much interest in helping him out. The Tribune’s headline: “Cops find deceit—but no one cares.”

Sherwin eventually found a willing partner in the Legislative Advisory Committee on Public Aid, a body put together by state legislators eager to take a stand against government waste. The detective also learned that Taylor was wanted on felony welfare fraud charges in Michigan. At the end of August 1974, she was arrested in Chicago, then released on bond in advance of an extradition hearing. A month later—and the day after the Tribune told her story for the first time—Linda Taylor didn’t answer when her name was called in Cook County Circuit Court. The most notorious woman in Illinois was on the lam.

On Aug. 12, 1974—four days after Linda Taylor told Jack Sherwin she’d been robbed—Lamar Jones met his future bride. The 21-year-old sailor was working in the dental clinic at Chicago’s Great Lakes Naval Training Center when a beautiful woman walked in to get her teeth cleaned. Something about her was totally fascinating, Jones remembers. “I met her because she was pretty and I was shooting game to her,” he says. “I guess her game must’ve been stronger than mine, because I met her that Monday and [got] married that Saturday.”

Jones thought he was lucky to get hitched to the 35-year-old Linda Sholvia. She was beautiful, with the smoothest skin he’d ever seen. She also gave him $1,000 as a wedding present, and he had his pick of fancy new cars. But Lamar and Linda’s marriage lasted only a little longer than their five-day courtship. A few weeks after they exchanged vows, Linda was arrested. When Jones paid her bond, his new wife fled the state. To make things worse, she stole his color TV.

The young Navy man realized that something was amiss with his new bride even before the television went missing. When she showed him a degree from a university in Haiti, he noticed that it said Linda Taylor, not Linda Sholvia. Jones says Linda had five mailboxes at her residence at 8221 S. Clyde Ave., and she’d get letters in all five, addressed to different names. He got a bit uneasy when Linda told him, after they were married, that he was her eighth husband. She also had a “sister” named Constance who seemed more like her adult daughter.

Her skin was so pale and smooth, he says, that she could look Asian, or like a light-skinned black woman, or even white. One night, though, he woke up before dawn and saw that his bride’s smooth skin wasn’t so perfect—she had “1,000 wrinkles on her face.” After he caught this illicit glimpse, Linda locked herself in the bathroom for an hour. When she came out, she looked like a whole new person.

Photo illustration by Holly Allen

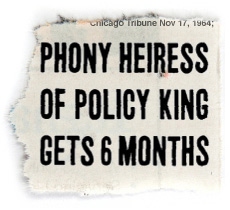

Once Linda fled the state, that ended all hope of salvaging their three-week marriage. Jones says at that point he cooperated with authorities, who wiretapped his phone and traced one of the fugitive’s calls. On Oct. 9, “Constance Green” was apprehended in Tucson, Ariz., on behalf of Chicago police. Three days later, the Tribune’s George Bliss wrote that “the 47-year-old ‘welfare queen’ was being held in a [Tucson] jail.” It’s the first instance I’ve found of someone being branded a “welfare queen” in print.

A month after his wife was brought back from Arizona, Lamar Jones testified against her in front of a Cook County grand jury. Jones says that around the time of that proceeding, he was shuffled into a car with another witness and told they had something in common: They were both married to Linda (or maybe it was Connie) at the same time. That was a surprise to Jones. His wife had told him that husband No. 7 was dead.

Circuit Court of Cook County

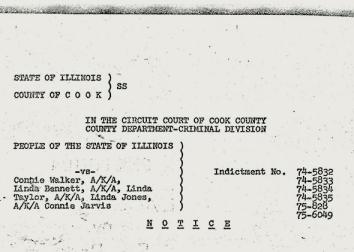

On Nov. 13, Taylor was indicted on charges of theft, perjury, and bigamy. (The bigamy charges were later dropped.) In court records listing the counts of the indictment, the defendant’s name is recorded as Connie Walker, aka Linda Bennett, aka Linda Taylor, aka Linda Jones, aka Connie Jarvis. She was either 35, 39, 40, or 47 years old, depending on whose story you believed.

Given all the superlatives that attached themselves to Taylor—the executive director of the Legislative Advisory Committee on Public Aid told the Tribune, “She is without a doubt, the biggest welfare cheat of all time”—the charges against her weren’t all that impressive. One of the assistant state’s attorneys prosecuting Taylor told the UPI that all the rumors were “probably” true. “But what makes me angry about all the stories is that most of them are not indictable," she said. "We simply don't have the facts on all of those things.” The Tribune reported that Taylor was filching every form of public assistance imaginable: Social Security, food stamps, Medicaid, and Aid to Families With Dependent Children. But the hard evidence—canceled AFDC checks, and Medicaid ID cards under multiple names—allowed the state to charge her with stealing $8,000 from the public coffers, nothing more.

Taylor’s welfare fraud case stalled in the courts for long enough that her 1974 indictment remained campaign fodder for Ronald Reagan in 1976. The yawning chasm between “probable” and “indictable” was wide enough for Reagan to label Linda Taylor a public scourge, and for the candidate’s critics to claim she was a media myth. In October 1976, Reagan—who had lost that year’s GOP nomination to Gerald Ford—devoted one of his regular radio commentaries to updating the story of the “welfare queen, as she’s now called.” (While I haven’t found any examples of him saying “welfare queen” on the stump in 1976, he did use the term in this radio address.) According to Reagan, it had now been revealed that this woman (he still didn’t identify her by name) had operated in 14 states using 127 names, claimed to be the mother of 14 children, was using 50 addresses “in Chicago alone,” and had posed as an open heart surgeon. She also had “three new cars, a full-length mink coat, and her take is estimated at a million dollars.”

While Reagan sourced his report to “the chief investigative reporter of the Chicago Tribune,” I can’t find anything in the Tribune to support the claim that Taylor’s take reached $1 million. The bits about the new cars and the fur coat were accurate, though. And the part about her posing as a heart surgeon—that was probably true, too.

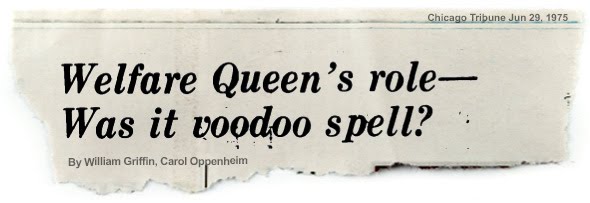

The Tribune printed so many incredible stories about Linda Taylor that it really wasn’t necessary for Reagan to exaggerate the figures. As he’d said, Taylor had posed in Michigan as a heart surgeon named Dr. Connie Walker and, in the Tribune’s telling, “drove a new Cadillac bearing the physicians’ staff and serpent on both doors and the word ‘Afri-med’ on the rear.” According to other accounts, she allegedly practiced voodoo and had traveled to Jamaica after being released from jail. In September 1975, Taylor’s son-in-law and her daughter Sandra were indicted for getting fraudulent Aid to Families With Dependent Children payments. A month later, with Taylor out on bond and awaiting trial for welfare fraud, she told police that two men with guns had barged into her apartment and stolen $17,000 in jewelry—a crime reminiscent of those phony burglaries that led the Chicago police to start digging into her tangled life.

In February 1976, Jack Sherwin dropped in on Taylor’s home to deal with yet another burglary case. This time, Chicago’s welfare queen was the alleged perpetrator, not the victim. Taylor allegedly had snatched $800 worth of items from a woman she’d been living with. The police found the victim’s electric can opener, color TV, and fur coat squirreled away in Taylor’s apartment building, though a three-piece polka-dot pantsuit was not recovered. The officers also found two small children living in squalid conditions. The boys, a white 7-year-old and a black 5-year-old, were taken into protective custody.

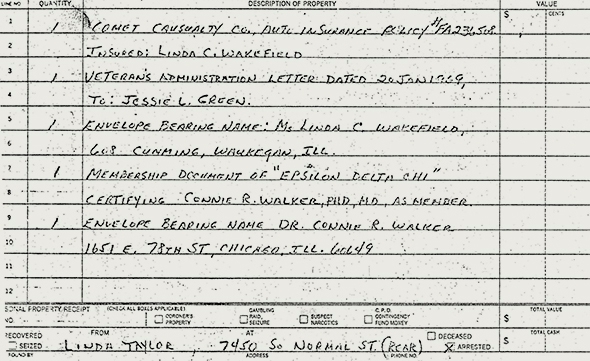

The subsequent news stories focused on Taylor’s car, which was impounded because she’d allegedly used it in the commission of the crime. The headline in the New York Times: “ ‘Welfare Queen’ Loses Her Cadillac Limousine.” The newspapers did not mention all the other evidence found in Taylor’s home. A partial rundown of the items seized, as listed in the police report:

Circuit Court of Cook County

- phone bill carrying the name Mary Stevenson, c/o Willtrue Loyd

- Chicago Motor Club document bearing the name Yepez Juventino

- a Chicago Motor Club card for Linda C. Jones

- an AMOCO Motor Club card for Linda C. Wakefield

- Allstate Insurance Co. letter to Linda Bennett

- a department store credit card in the name Patricia M. Parks

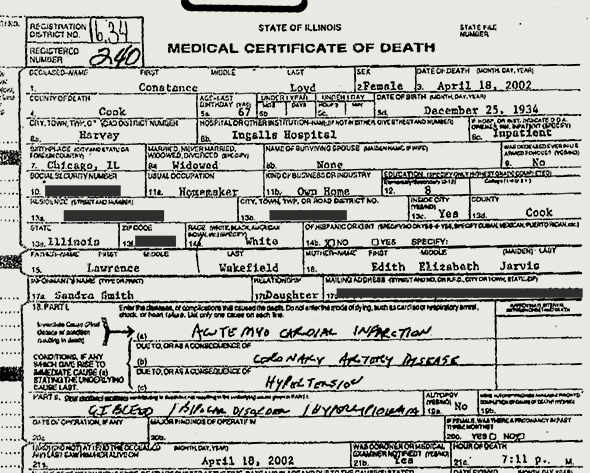

- coroner’s death certificate for Frank Brown

- business letter from Martin Fertal attorney at law to Mrs. Lillian McIntosh

- Veterans Administration letter to Mrs. Constance Howard

- auto insurance policy in the name of Linda C. Wakefield

- Veterans Administration letter to Jessie L. Green

- membership document of “Epsilon Delta Chi” certifying Connie R. Walker, Ph.D., M.D., as member

- membership card for Epsilon Delta Chi in name Dr. Linda C. Wakefield

- birth certificates for children named Willie and Hosey

- a personal letter signed “Husband Ray”

- a rent receipt from Mrs. Linda Ray to Everleana Brame

- a mortgage receipt for J&P Parks

- a mortgage notice, for the same address, for Linda C. Wakefield

- a receipt for a safety deposit box in the name Linda C. Jones

- a telephone bill addressed to Sherman F. Ray

- envelope addressed to Linda Ray

- two lottery tickets

In addition to this remarkable collection of documented pseudonyms, Taylor’s cache includes many other people’s names—on a credit card, a telephone bill, and all manner of documents. These are not aliases. They are possible victims.

For much of the 1970s, Taylor had consistent legal representation from celebrated black Chicago attorney R. Eugene Pincham. In the run-up to Taylor’s welfare fraud trial, Pincham—who managed to delay the proceedings for years, winning continuance after continuance—positioned his client as a victim of coldhearted, overreaching prosecutors. “It would be a pretty sorry situation if the state tried to prosecute and send to jail everybody from the South Side that took welfare money they didn't have coming," he told the Tribune in 1976. "There'd just be nowhere to put them.” Prosecutors, meanwhile, called Taylor a “parasitic growth,” a leech who gleefully extracted taxpayers’ money.

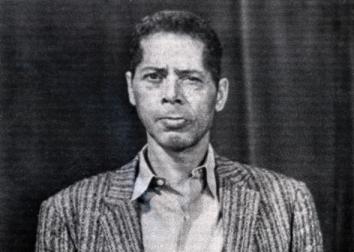

Taylor didn’t help her legal team sell the idea that she was a piteous victim. The AP described her courtroom attire as “brightly colored mod outfits with sparkling rings and bracelets,” a gaudy wardrobe that gave TV crews and newspaper photographers the perfect welfare queen action shot. Isaiah Gant, who eventually took over Taylor’s case from his colleague Pincham, says she’d position herself to be seen by the cameras but would not deign to speak. “Doing interviews would have made her commonplace,” Gant says.

The trial of the welfare queen finally began in March 1977, two-and-a-half years after Det. Jack Sherwin cited Taylor for making a false burglary report. Sherwin testified that he’d observed Taylor with green Medicaid ID cards carrying the names Connie Walker and Linda Bennett. An FBI handwriting expert, too, took the stand to say that 13 of the Walker and Bennett signatures on her monthly AFDC checks, which ranged in value from $249 to $464, were “definitely” written in Taylor’s hand.

Photo by Charles Knoblock/AP via Corbis

It took the jury seven hours to find Taylor guilty. Judge Mark Jones sentenced her to two to six years for theft and one for perjury, with the terms to be served consecutively. The Chicago Sun-Times reported that Taylor, always poker-faced in court, had tears in her eyes when she learned her fate.

Shedding a tear is a rational response to a felony conviction. Taylor’s behavior before, during, and after the trial, by contrast, was consistently bizarre and brazen. While Taylor was awaiting sentencing, Judge Jones revoked her bond when the home address she’d given a probation officer turned out to be a vacant lot. Though she’d been called Linda Taylor throughout the trial, she now told a different story: “They're looking for Linda Taylor, and I'm not Linda Taylor.” A few months later, she was released from custody briefly while her case was on appeal. According to Cook County prosecutor James Piper, she subsequently “applied for welfare, claiming she needed the money for medical purposes.” Piper told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat that she was suspected of falsifying information on the application.

Was Taylor a cold and calculating grifter? Was she mentally ill? Isaiah Gant, who has been an attorney for nearly four decades, says his onetime client “was a scam artist like I have never run across since.” Gant, now an assistant federal public defender in Nashville, Tenn., says Taylor could change personalities in an instant. “If she wanted to be a ho, she could be a ho. If she wanted to be a princess, she could be a princess,” he says. “The woman was smooth.”

When she was preparing to stand trial for the 1976 theft of an electric can opener and fur coat, another of Taylor’s attorneys had asked the court to have her submit to a behavioral clinic examination. In that petition, her lawyer explained that Taylor’s former attorneys had informed him “that the Defendant was incapable of knowing whether or not she was telling the truth.” In addition, there were “reports of two psychiatrists who examined her which referred to her as being psychotic and unable to understand the nature of the proceedings.”

The petition for a medical examination was ultimately denied. In February 1978, the welfare queen entered Illinois’ Dwight Correctional Center. According to the Sun-Times, while incarcerated she worked cleaning her fellow inmates’ cottages. As of March 1979, she had a minor violation on her prison record, having “allegedly used state-owned materials to make cushions and sell them.”

After that, Linda Taylor disappeared from newsprint. By the end of the 1970s, Taylor had become a historical footnote. The welfare queen was forgotten before anyone figured out who she really was.

It took a crew of cops nearly 20 hours to count all the cash. There were coins and bills stuffed in the furniture, sheathed in piles of clothes, and stuffed inside laundry bags, pillowcases, cardboard boxes, and an old foot locker. A deputy superintendent said that it was the biggest haul he’d come across in 23 years on the force. The final tally: $763,223.30.

The Chicago police had gone to Lawrence Wakefield’s house on Feb. 18, 1964, after getting a report that he was deathly ill. When cops and firemen arrived on the scene, they spotted coin wrappers and betting slips—the calling cards of a gambling operation. Just hours after the authorities raided his living room, Wakefield died in the hospital of an intracranial hemorrhage. His death certificate identifies him as a 60-year-old “Negro.”

Photo by UPI via Corbis

Everybody on the South Side of Chicago knew Wakefield was a hustler, but they didn’t think he was this good at it. Wakefield operated a policy racket, a kind of underground lottery that thrived in the Windy City until the 1970s. Neighborhood proprietors fished numbers out of a drum, and bettors won by matching the resulting combination—the UPI termed it “the poor man’s stock market.”

By the mid-1960s, the Italian mob had muscled most of the black kingpins out of the policy game, but they hadn’t hassled the shabby, modest-living Wakefield. Why bother? The guy was clearly small time.

It was probably true that Wakefield’s glory days were long gone—some of the greenbacks the cops uncovered were a half-century old. But the money was still real, even if he preferred hoarding it to spending it. Since he hadn’t been charged with any crime, the police didn’t confiscate Wakefield’s bounty. Now, it wasn’t clear how to disburse this windfall. Wakefield hadn’t made out a will, and he had no known living relatives.

When photos of all that cash hit the Chicago papers, more than a dozen alleged heirs emerged to grab for the money. One contender was Rose Kennedy, a 66-year-old white woman who said she was Wakefield’s common-law wife. According to Kennedy, she and her late husband—who had died 30 years earlier—had invested $160,000 to start their own policy operation in Chicago. When her husband passed away, Kennedy explained, Lawrence Wakefield had taken the reins of their operation, and she’d become his live-in companion.

Kennedy’s toughest competition for the loot was a woman named Constance Wakefield. On April 18, 1964, the city’s black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, splashed a headline across its front page: “Dead Policy King’s $763,000 Demanded By His ‘Daughter’: Has Papers To Prove Her Claim.” The first two paragraphs of the story read skeptically:

A 29-year-old woman who claims to be the daughter of the late policy king, Lawrence Wakefield, has unfolded a fantastic story of "plots" and intrigues which separated her from her "father."

The claimant, Constance Beverly Wakefield, who lives on Chicago's Northside, showed the DEFENDER an array of "documents" which, she claims, prove she is the daughter of Wakefield.

Graphic by Slate.

The Defender’s reporter described an unusual scene at Constance Wakefield’s home, which was protected by a bodyguard, decorated with “odd figurines,” and featured a myna bird that “constantly squawked the name ‘Lawrence.’ ” The 29-year-old Constance, who showed “signs of having been a beauty in her younger days,” produced a 1935 birth certificate listing her parents as Lawrence R. Wakefield and Edith L. Jarvis. Constance said she’d grown up in Blytheville, Ark., and had believed until recently that this Edith Jarvis was her grandmother.

It got stranger from there. Constance told the Defender that Rose Kennedy, Lawrence Wakefield’s purported common-law wife, was no such thing. She also accused Kennedy of trying to poison her, saying, “The doctors said I had swallowed enough strychnine to kill a dozen people.” And in just the last few weeks, she reported, police had captured two white men trying to break into her house; a “swarthy Italian” had threatened to kill her; and her bodyguard had narrowly thwarted an attempt to blow up her 1964 Cadillac. A few days after that, the Associated Negro Press wrote that Constance Wakefield Steinberg—she was a “light-skinned Negro woman with a ‘Jewish’ surname”—“reported to police that her 11-year-old son, John, had been kidnapped and that she had received a number of threatening calls.”

Whether she was going by Constance Wakefield, Linda Taylor, or any other name, the future welfare queen never went for subtlety. She was a woman of great ambition, and she conjured a universe in which the forces arrayed against her were equally extraordinary. Someone was always trying to kill her, or steal from her, or kidnap her, or take her children. These stories rarely checked out. Her son John, the Chicago Sun-Times would report, hadn’t been kidnapped. He was found by FBI agents wandering near his house, and explained that he’d run away after a fight with his sister. Census records and Lawrence Wakefield’s own death certificate reveal that Edith Jarvis was not Wakefield’s wife, as Taylor had asserted—she was his mother. When Taylor went to probate court to press her claim to the Wakefield fortune, even more of her story fell apart.

In this and many of her other battles, Linda Taylor’s weapons were documents, paperwork of uncertain provenance that buttressed her version of events. Though her birth to Lawrence and Edith did not appear in contemporaneous records, she procured a delayed birth certificate from the doctor who she claimed had delivered her. She also furnished a pair of Lawrence Wakefield’s heretofore-undiscovered wills. The first, which dated to 1943, included a description of Wakefield’s daughter that matched her own, “specifically describing a scar and a mole and their location on her body,” the Tribune reported. The second will, from 1962, indicated that Wakefield had $2 million, that the vast majority of that lucre should go to his daughter, and that Rose Kennedy—who Taylor maintained was Lawrence Wakefield’s housekeeper, not his common-law wife—was entitled to precisely $1. "She is no good and will try to take everything from my baby,” the will read, according to the Tribune. “She has stoled enough from me since the death of my Edith."

None of this evidence—the delayed birth certificate, the will that conveniently trashed her primary rival—convinced Cook County Assistant State’s Attorney Gerald Mannix that he was dealing with Lawrence Wakefield’s real daughter. A long way from Chicago, he found someone who could help him prove it.

“A surprise witness testified in Probate court yesterday that Miss Constance Wakefield, who claims to be the illegitimate daughter of the late Lawrence Wakefield, policy king, and thus heir to his fortune, actually is Martha Louise White,” the Tribune reported on Nov. 10, 1964. Hubert Mooney, who claimed to be Martha’s uncle, explained that his niece was born in Summit, Ala., around 1926, making her about 38 years old—nine years older than she’d claimed to be in the guise of Constance Wakefield. Martha, Mooney said, was the daughter of his sister Lydie and a man named Marvin White. The court didn’t have to take his word for it. Hubert’s 84-year-old mother came from Tennessee to testify that she’d assisted in her granddaughter Martha’s birth.

Mooney said he’d seen his niece most recently in Arkansas—the state where “Constance Wakefield” had grown up, according to her interview with The Chicago Defender. He’d also run into her in Oakland, Calif. On that occasion, she’d asked her uncle to bail her out of jail. According to the Chicago Sun-Times, the assistant state’s attorney produced fingerprints and “police records from Oakland, which he said were those of Miss Wakefield, listing arrests for prostitution, contributing to the delinquency of a minor, and assault.” A police expert testified that those fingerprints matched those of Beverly Singleton, a woman who’d been arrested the year prior for assaulting a 12-year-old girl. Constance Wakefield, it seemed, was many people, but she probably wasn’t Constance Wakefield.

Photo illustration by Holly Allen

This dramatic testimony didn’t clear everything up. For her part, “Constance Wakefield” said she knew Hubert Mooney but that she was not Martha Louise White. She also denied that she was the woman identified in all those criminal records, though she did confess that she’d been charged with assault in Oakland.

Weighing all the evidence, Judge Anthony Kogut cited Taylor for contempt of court and sentenced her to six months in jail. She wouldn’t get any of Lawrence Wakefield’s money, the balance of which would go to Rose Kennedy, the policy king’s common-law wife.

For Hubert Mooney, who died in 2009, this was a jarring experience. His daughter Joan Shefferd says Mooney was from a different era, and that he was a very prejudiced man. Taylor’s behavior, she says, made her father angrier than she’d ever seen him. His niece’s lying and scheming were one thing, but there was something else he’d never understand. Why was Martha Louise White passing herself off as a black woman?

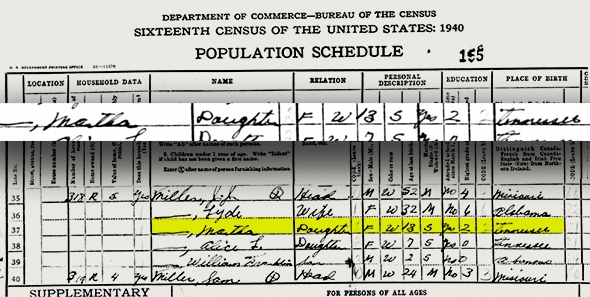

Forty-five years before she became the welfare queen, Linda Taylor was a little girl on a farm in Mississippi County, Ark. The 1930 census identifies her as Martha Miller, one of three children of Joe Miller, a cotton farmer. Joe’s wife was Lidy Miller (written in other documents as Lyde or Lydie).

Though her Uncle Hubert testified that Taylor was born in Summit, Ala., the census says her place of birth is Tennessee. She’s listed as 4 years old in 1930 and 13 in the 1940 survey, meaning she was born sometime between 1925 and 1927. As of 1940, the 13-year-old girl had attended school, but had gone only so far as the second grade. And in the box labeled “color or race,” she’s marked with a “W” for white, just like everyone else in her family.

Courtesy National Archives. Graphic by Slate.

Those who, back then, knew Linda Taylor as Martha remember her as a willful child: If you told her she couldn’t do something, she’d set out to prove you wrong. She also didn’t look like her parents and siblings. Shelby Tuitavuki, who grew up near the Miller family in Arkansas, says Taylor had long black hair and dark skin. “I think she could’ve been black,” the 71-year-old Tuitavuki says. Joan Shefferd, who’s 62 and lives in Kansas, doesn’t believe Taylor was really black. She says her cousin’s pigmentation was a product of her family’s Native American heritage.

It’s possible that Taylor’s biological father—identified by Hubert Mooney as a man named Marvin White—was black. Or perhaps a family secret was buried a few more generations back. No matter her bloodlines, the more persistent truth was that Martha Miller—who would later shed her childhood name for a nearly endless set of aliases—was a racial Rorschach test. She was white according to official records and in the view of certain family members who couldn’t imagine it any other way. She was black (or colored, or a Negro) when it suited her needs, or when someone saw a woman they didn’t think, or didn’t want to think, could possibly be Caucasian.

The young Taylor moved between two very different worlds in the Jim Crow–era South, a type of flexibility that could get a young woman into trouble. Shelby Tuitavuki says that around 1950, Taylor had an affair with Tuitavuki’s uncle, a white man with blond hair and blue eyes. Tuitavuki says her aunt flew into a rage, throwing rocks at her husband’s car and jeering at his paramour, shouting, “Come out, you black nigger!”

It wasn’t just Taylor’s skin and choice of men that drew scorn. By the early 1950s, she had four children, and they didn’t all look alike. The first, Clifford, was born in 1941, when she was a teenager. He was white. The second, Paul—who, for reasons that have been lost to history, was nicknamed Tojo after the Japanese prime minister—was born in Oakland, Calif., in 1948. On Paul’s birth certificate, his mother is listed as Connie Martha Louise White, a 21-year-old white housewife. (Even at this early stage, Taylor was trying on new names.) The father was Paul Stull Harbaugh, a 24-year-old white Ohio native serving in the U.S. Navy. Paul Jr.’s race is also recorded as white. His skin, though, was dark—much darker than his mother’s.

Her third son, Johnnie, was born in 1950. A short while later, she had a daughter, Sandra. Johnnie, like his brother Cliff, was unmistakably white. Sandra, like her mother, was more racially ambiguous.

Taylor and her children lived an itinerant existence. “We would go from Arkansas to Mississippi, then from there we’d go to Ohio, California, Chicago,” her son Johnnie remembers. Everywhere they went, there was trouble—the kind you’d expect when a mixed-race family traveled through the Deep South.

“If Paul was with us, people used to say, We’ll give you $10, give us some of his hair,” says Johnnie, who is now 63 years old. When they lived in Louisiana, Paul wasn’t allowed to eat inside a white-owned restaurant. Johnnie remembers taking his food outside and joining his older brother under a tree. The two children were ordered to split up, he says, and told there’d be big problems if they were seen together again. His mother was called “a nigger lover and all kinds of prejudiced stuff,” Johnnie says.

They spent more time in cars than houses, and Johnnie associates each place with a different make and model: a little green Nash in El Paso, Texas, a white Oldsmobile 88 station wagon in Peoria, Ill. When it was time to leave, they left quickly, with each child’s belongings in a single bag. They lived like fugitives. “As a kid, I didn’t know from one year, one day, one second to the next where I would be tomorrow,” Johnnie says.

Cliff left home in his early teenage years, Johnnie says, and then it was just him, Paul, and Sandra. It was them against the world—and often them against their mother. Johnnie says Taylor was not a loving person. She used to beat him, he says, because “I was the odd one”—a white child who saw himself as a black sheep.

When Chicago prosecutors unmasked Constance Wakefield in 1964, they revealed that she’d been charged in Oakland with (among other things) contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Later, in Arizona and Illinois, she’d have children taken from her after police found signs of neglect. Throughout her life, wherever she went, she was always picking up children and losing them, other people’s and her own. When Johnnie was young, he says, his mother would often hand her kids over to friends, family, and tenuous acquaintances, with no indication of when or if she’d return. In the mid-1950s, she left Paul with a black family in Missouri. After a brief reunion, she left him again, this time with a family in Chicago. His siblings wouldn’t see Paul again for many years.

Johnnie loved his brother, and he missed him. “I asked her all the time, Where’s Paul? When is Paul coming back?” His mother would say that he was fine, that he was with his grandparents. But Johnnie knew she wasn’t telling the truth. To him, it seemed as though she’d succumbed to prejudice and hardship—that she’d given up on their mismatched family, ditching the child who happened to have the darkest skin.

Life was good in Chicago. Johnnie, his mother, and his sister had a furnished apartment, and the kids all got new bicycles, something they never had when they were younger. Now that they were under the protective wing of Lawrence Wakefield, what could possibly go wrong?

Taylor’s relationship with the black policy king was not a total fantasy she’d conjured in a bid to get a dead man’s money. Johnnie isn’t sure how his mother knew Wakefield, but he says it was clear when they got to Chicago around 1960 that the two of them had history. Johnnie says that his mother would call Lawrence “dad,” and Lawrence would call her his daughter. They didn’t have a sexual relationship so far as he knows, and Wakefield seemed driven to take care of Taylor and her children. They always had money, Johnnie says, and even bodyguards.

Photo by Josh Levin

In the early 1960s, they settled in at 1109 N. Damen Ave., in Chicago’s Ukrainian Village. Wakefield was down the block in a building dotted with frosted-glass windows. As a kid, Johnnie says, he carried a few bags for the old man, dropping them off at a jewelry store a half-mile from his house.

Even if he was running numbers for an illegal gambling racket, Johnnie remembers this as an idyllic time—a period of comfort and stability after years on the run. And then, suddenly, Lawrence Wakefield died. “It was like the whole Earth flipped on us,” Johnnie says.

For all that he’d done for them in Chicago, Lawrence hadn’t provided for them upon his passing, unless you believed the dubious wills that “Constance Wakefield” waved around in probate court. With the family’s breadwinner out of the picture, Taylor and her children became vagabonds again, moving from house to house on Chicago’s predominantly African-American South Side. For Johnnie, this was devastating, an unwelcome return to the disjointed life he thought he’d left behind. Johnnie’s path to delinquency was now set. At 14, he says, he became a full-time criminal. For the next decade, he was in and out of juvenile detention and prison.

Her son Cliff had left home as a teenager. Paul had been given away as a child. Now, Johnnie was roaming the streets. And on March 3, 1966, The Chicago Defender reported that “Constance’s” daughter was gone.

Sandra Stienberg, 13, of 4325 S. Calumet Ave., has been missing from home for 18 days. Her mother, Mrs. Constance Wakefield, says she believes her daughter has been abducted. If she is seen, please notify Chicago police at WA 2-4747.

There’s almost no chance that Sandra was really kidnapped. Two years prior, Taylor had falsely reported that Johnnie had been abducted. He says now that his mother likely just wanted the cops to do the hard work of tracking him down after he’d left home of his own volition.

In 1967, she’d try the same line again, telling Chicago police that another of her children had been taken. When the cops investigated, they found that the child wasn’t missing. They also discovered that the kid didn’t belong to her.

The first time I spoke with Raymond Pagan, he asked if I’d talked to any of the other kids that Taylor had kidnapped. (I had not.) Raymond, who is 46 and lives in Chicago, was very young when he was abducted—his mother says he was 3 when he was returned to her—but he says he remembers other children, and that they were all jammed into the same bed. “Thank God I was a kid and I didn't know what the hell was going on,” he says. Still, he had nightmares about Taylor for years.

Raymond’s mother Rose Termini wasn’t worried about leaving her son with Linda Taylor—after all, she had been a good babysitter for her sister’s daughter Anna. When Termini needed someone to watch Raymond for a couple of days, she decided she’d leave him with Taylor, too. “She acted friendly, nice, kind, and I seen her with her kids, and I seen my niece there,” the now 62-year-old Termini says. There were four or five children there in all, she remembers. “I go, OK—then I trust her. But then when I went back for my son, he was gone.”

Photo by Josh Levin

Termini says she reached Taylor on the phone a few times, and she would assure her that she’d return Raymond soon. But she never did. Termini remembers taking the bus to the far South Side to search for her son, but Taylor kept changing her address. She didn’t call the police because she was just 16 years old, and she was afraid of what Taylor would do to her and her family. “I was scared of the lady because she had so much money, and I didn't know how to get to her,” she says. “She had money, jewelry, cars—I mean, she had almost everything she wanted.” Termini says she had a nervous breakdown, and that she ended up in the hospital for months. “I would keep on saying, I gotta find my son, I gotta find my son.”

Termini claims it took her two years to get Raymond back. Her husband, who was in a gang called the Dragons, passed along a message to Taylor’s daughter Sandra that it was time for the abduction to end. Termini recalls that Sandra—who, like her, was a teenager at the time—would say, “I can't bring Raymond to you because [of] my mother.” But she says Sandra eventually relented, telling her mother that she was taking Raymond to a friend’s place for just one night. “Ever since then, [Raymond] stayed with me,” Termini says. And after that, she never saw Sandra or Linda Taylor again.

Johnnie Harbaugh says Raymond and Raymond’s cousin Anna both stayed with Taylor, and “she didn’t want to let either one of them go.” He doesn’t know how Rose Termini got Raymond back, but he says he’s the one who rescued Anna. Johnnie says that when Taylor refused to part with Anna, he broke into Taylor’s house early in the morning, snatched the baby, and took the little girl to her mother, Lorraine Termini, on the “L” train.

Lorraine Termini died in 2006, and Johnnie’s sister Sandra Smith has refused all interview requests. There is one third-party account that references the Termini kidnappings. In March 1975, when Taylor was waiting to be tried for welfare fraud, the Chicago Tribune’s George Bliss and William Griffin wrote that in 1967, Taylor had asked the police to find her son, “Lena Womack.” The cops discovered that the 19-month-old Lena was really Lorraine Termini’s child, and they reported that Johnnie had returned the baby to its real mother.

Johnnie says the Tribune got part of the story wrong: Lena was Lorraine’s daughter, Anna, not a baby boy. He explains that Taylor, who at various times went by Constance Womack, simply gave the child a new name. The Tribune article also says that Lena/Anna was returned in 1967; Rose Termini’s account places the kidnappings slightly later. Johnnie, Termini, and the Tribune all agree, though, that Linda Taylor took children. The only question is how many.

In another Tribune story, Bliss and Griffin noted that Linda Taylor had been arrested twice in the 1960s for absconding with children, though she wasn’t convicted in either case because the little ones were returned. The reporters also laid out a possible motive. “Chicago’s welfare queen,” they wrote, “has been linked by Chicago police to a scheme to defraud the public aid department during the mid-1960s by buying newborn infants to substantiate welfare claims.”

This theory is a little hard to believe. Given Taylor’s ability to fabricate paperwork, acquiring flesh-and-blood children seems like an unnecessary risk if all you're looking to do is pad a welfare application. Her son Johnnie believes his mother saw children as commodities, something to be acquired and sold. He remembers a little black girl—he doesn’t know her name—who stayed with them for a few months in the early 1960s, “and then she just disappeared one day.” Shortly before Lawrence Wakefield died, Johnnie says, a white baby named Tiger showed up out of nowhere, and then left the household just as mysteriously. I ask him if he knew where these kids came from or who they belonged to. “You knew they wasn’t hers,” he says.

Before Wakefield’s death, Johnnie says, his mother’s behavior was unconscionable. After her benefactor passed away in February 1964, it got even worse. In the early 1960s, Taylor had a few babies who came from who-knows-where. Suddenly there were a whole lot more, kids like Anna and/or Raymond—and maybe a boy who was taken from his mother’s arms at Chicago’s Michael Reese Hospital.

On April 18, 1964, The Chicago Defender ran its interview with “Constance Wakefield,” the one in which she claimed to be the rightful heir to her father Lawrence’s fortune. Nine days later, a newborn child was kidnapped by a woman dressed in a white nurse’s uniform. Dora Fronczak told police that the mystery woman whisked away her son Paul Joseph, telling the new mother that her baby boy needed to be examined by a doctor. Witnesses said the ersatz nurse carried the infant through a rear exit and disappeared.

Photo by AP via Corbis

The Fronczak case transfixed Chicago and the nation. The Tribune, the Sun-Times, and the national wire services printed eyewitness accounts, sketches of the suspect, diagrams of the kidnapper’s probable path, and the family’s pleas for their child’s safe return. Within a day, 500 policemen were working the case, including 50 FBI agents. They were looking for a woman between her mid-30s and mid-40s, around 5-foot-4 and 140 pounds, with close-set brown eyes. Nine months after the kidnapping, the Tribune reported that a staggering 38,000 people had been interviewed in connection with the case, and that 7,500 women had been eliminated as suspects. Still, the baby-snatching nurse remained at large.

Did Linda Taylor pull off one of the most notorious kidnappings of the 1960s? In early 1975, law enforcement officials got a tip from one of Taylor’s ex-husbands that she “appeared one day in the mid-1960s with a newborn baby, altho[ugh] she had not been pregnant.” Her explanation, the Tribune said, was that “she hadn't realized she was pregnant until she gave birth that morning.”

Later that month, the Tribune revealed that Taylor had reportedly told police in 1967 “that she had given birth to a boy in Edgewater Hospital on Dec. 13, 1963—four months before the birth and kidnaping of the Fronczak baby. That child, she said, was living with foster parents in Chicago Heights.” Police discovered that the birth certificate for this supposed baby was signed by Dr. Grant Sill—the same doctor who had provided a bogus delayed birth certificate showing she was Lawrence Wakefield’s daughter. Dr. Sill, who is now deceased, had agreed to stop practicing medicine in 1970 to avoid prosecution on charges of “selling dangerous drug prescriptions to youngsters.”

Johnnie says his mother often claimed that she worked in a hospital, and that she’d wear a nurse’s hat. Rose Termini, without any prompting, begins the narrative of her son’s kidnapping by saying that Taylor “once told me she was a nurse and she got around a lot with kids.” According to Termini, Taylor would often dress in a white uniform—she says she saw the getup with her own eyes.

In 1977, a man named Samuel Harper told police prior to Taylor’s sentencing for welfare fraud that he believed she had kidnapped Paul Joseph Fronczak. He explained that he was living with her at the time, that several other white infants were in her home, and that she left the house in a white uniform on the day of the kidnapping. Johnnie Harbaugh confirms that Harper, who was 69 years old in 1977 and likely died many years ago, lived with his mother for a period in the 1960s. If anyone was in a position to know what Linda was up to, Johnnie believes, it was Sam Harper.

Jack Sherwin, who retired from the Chicago Police Department in the mid-1990s, says he saw a composite drawing of the Fronczak kidnapper in an FBI office. “I looked at it for a second and knew it was her,” he says. In police reports from the 1970s, Taylor is listed at 5-foot-1 and 140 pounds with brown eyes—not that far off from the suspect’s description. Sherwin says she also had a station wagon at that time that matched the description of the potential getaway car. He believes she was “guilty as hell.”

And yet, Linda Taylor was never charged in the kidnapping of Paul Joseph Fronczak. Ron Cooper, a retired FBI agent who worked on the Fronczak case in the 1970s, says that they “had no cooperation from people around her.” Everyone who talked “would tell you a story and it would just sort of be a flim-flam thing, and it wouldn’t make any sense.” If she had taken Paul Joseph in 1964, he was long gone.

Johnnie says he doesn’t know anything about the Fronczak case specifically. He’s always suspected, though, that his mother sold the baby she called Tiger—that would explain her evasiveness, and how an infant could come and go with no explanation. Tiger’s whereabouts remain a mystery. The same goes for the baby abducted from Michael Reese Hospital in 1964. Fifty years later, Paul Joseph Fronczak has yet to be found.

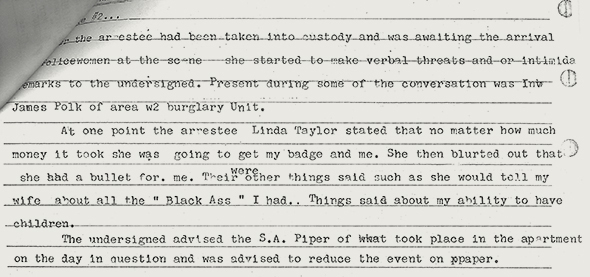

For Jack Sherwin, the fight to take down Linda Taylor was a multifront war. Some battles were contested face to face. “At one point the arrestee Linda Taylor stated that no matter how much money it took she was going to get my badge and me,” the detective wrote in one police report. “She then blurted out that she had a bullet for me. [There] were other things said such as she would tell my wife about all the ‘Black Ass’ I had.” Taylor also waged a disinformation campaign, calling Sherwin’s superiors to complain that the detective had it in for her. She even took the fight to the astral plane, jabbing sharp pins into a voodoo doll, one she told Sherwin that she’d made especially for him.

Sherwin did the digging that led to Taylor’s arrest for welfare fraud, and his testimony helped send her to prison. But four decades after he first met Linda Taylor, the 74-year-old retired detective can’t help but feel that she beat him. She was his prize catch, but Sherwin ended up getting snared in her net.

Circuit Court of Cook County

From early August to the end of September 1974, Sherwin unraveled several lifetimes’ worth of Taylor’s scheming. As the detective neared a breakthrough, he paused the investigation to go on his honeymoon. Upon his return, he saw his case splashed across Page 3 of the Chicago Tribune. The paper reported that Sherwin and his partner had used their “blood-hound instincts” to uncover Taylor’s public-assistance scams. Sherwin’s shock at seeing these plaudits in print quickly turned to anger. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still fuming.

Having the story leak would’ve been bad enough. What made it much, much worse was that Sherwin’s superiors didn’t know he’d been digging into Taylor’s past. Sherwin says Taylor’s persistent complaints had succeeded—he’d been told to back off due to her allegations of harassment. Rather than heed that order, Sherwin and his partner gathered evidence off the clock. “I would’ve had it all put together in a bundle for the bosses,” he says. “They would’ve been happy.”

Instead, the department’s higher-ups learned about his unsanctioned sleuthing on the same day Tribune readers did. George Bliss’ article depicted Sherwin as a swashbuckling hero fighting desperately to convince anyone to take interest in this incredible case of welfare fraud. That didn’t go over well at headquarters. “The boss who was in charge of my office at the time—oh, was he irate,” Sherwin remembers. He believes the leak torpedoed his career.

It’s not just that Sherwin suffered professionally after the story hit the papers. In the aftermath of that Tribune article—and the one published two weeks later that gave Taylor her famous nickname—Sherwin and his partner were detailed to the investigative unit of the state Senate’s Legislative Advisory Committee on Public Aid. The detective had been looking into a wide range of Taylor’s crimes, but now a police matter had become a political one. The welfare fraud, it seemed, was all that mattered.

For the Chicago burglary detective, Linda Taylor was never really the welfare queen. He believed she was a kidnapper and a baby seller. Maybe something worse.

Patricia Parks-Lee and her two little brothers went to Montessori school, and their mother took them shopping at the big department stores in downtown Chicago. Mrs. Parks, who was also named Patricia, earned her living as a schoolteacher. Her daughter describes her as polished, a woman with a master’s degree who hung out with college-educated types. Parks-Lee says that Linda Taylor, by contrast, looked weathered, like she’d done a lot of hard living. “She didn’t associate with people like that,” says Parks-Lee, who’s now 48. She believes her mother must have hired Taylor to keep house and watch the kids, nothing more. She says that Linda Taylor was the worst nanny they ever had.

Taylor took up residence with the Parks family in 1974. At that point, Patricia Parks was a healthy woman with three young children. Less than a year later, she was dead. At the time, Taylor was out on bail, awaiting her welfare fraud trial. The Tribune explained that she was now under investigation yet again after authorities “learned that Mrs. Parks reportedly had willed her home to Miss Taylor and had made her the beneficiary of ‘several’ insurance policies and the guardian of her three children.”

Parks-Lee was 10 years old when Taylor moved in, and her brothers were 8 and 6. Taylor’s daughter Sandra’s two children stayed at the house for a time as well. Sandra wasn’t around much, but Parks-Lee says she was friendly and jovial, at least compared to her mother. Taylor “wasn't nurturing,” Parks-Lee says. Her attitude toward children: “I don't wanna hear you, I don't wanna see you.”

Before Linda Taylor moved in, Parks-Lee had her fill of home-cooked Trinidadian cuisine: fish, rice, and homemade bread. Now, with her mother getting sicker and increasingly confined to her bed, she and her brothers barely had anything to eat—it was the only time in her life, Parks-Lee says, that she went to bed hungry. It got so bad that she found her brothers in the pantry with the door closed, trying to hide that they were eating dog biscuits.

Parks-Lee had been raised to never question her mother, and now she felt completely lost. “We didn't go to church anymore, we didn't associate with the people who were my mother's regular friends,” she says. Taylor was pulling off a slow-motion home invasion, and the only witnesses to the crime were a few small children. There was nobody around to answer the questions swirling in the 10-year-old girl’s head: Who was this woman who’d taken over their lives? And what did she want from them?

As Patricia Parks’ health declined, Taylor rearranged their home. She put Parks in her daughter’s room, and Parks-Lee moved in with her two brothers. Linda Taylor, the new woman of the house, took over their mother’s old room. “Linda would go in and feed her pills,” Parks-Lee says. The children were mostly banished to the back of the house, and Parks’ bedroom was always dark and closed off. Parks-Lee remembers that it was hard for her mom to talk. She would still smile, though, giving her children as much affection as she could muster.

“I never thought my mom was going to die,” Parks-Lee says. Taylor kept saying that Parks was going to get better, but her health never improved. And then, she was gone.

Patricia Marvel Parks passed away on June 15, 1975. She was 37. The death certificate identified the informant as Linda C. Wakefield, “friend.”

Taylor told the funeral director that Patricia Parks had cervical cancer. When her blood was drawn at the funeral home, however, the sample contained a high level of barbiturates. On Parks’ death certificate, the coroner indicated that she had died of “combined phenobarbital, methapyrilene, and salicylate intoxication.” There is no indication that she had cancer.

“She killed my mother,” Parks-Lee says. She’s so sure about what Linda Taylor did that she says it three more times: “She killed my mother. She killed my mother. I just, I mean—she killed my mother.”

For Patricia and her two brothers, their mother’s death was devastating. For the Chicago newspapers, this potential homicide was an opportunity to gawk at the welfare queen’s strange lifestyle.

Photo illustration by Holly Allen

The Tribune reported that “when investigators entered the dead woman's bedroom they found five lamps directed toward a hospital bed, a pair of witch doctors' masks hung on walls, candles, a voodoo manual, and a religious statue on a nearby table.” The paper quoted a woman named Frances Fearn who said she had introduced Parks and Taylor. Mrs. Fearn “said Miss Taylor had identified herself as Linda Mallexo, an African doctor who practiced voodoo.” She also noted that at “their first meeting, Miss Taylor told Mrs. Parks that she would die in six months.”

Linda Taylor used to tell people that she got her spiritual training in her supposed home country of Haiti. Johnnie says he remembers his mother practicing voodoo—or, her version of voodoo—as far back as the 1950s. “We lived in New Orleans and Albany, Louisiana, and all she did was that witchcraft stuff,” he says. Rose Termini, who says Taylor absconded with her son Raymond in the 1960s, says, “Oh yeah, she used to play with candles.” Parks-Lee remembers there being “potions” all over the house. The Tribune also found a woman named Jo Ann McFall who had paid Taylor $1,500 for a series of “spiritualism visits” in 1971. The article continued, “Miss McFall said she ended the sessions when one of Miss Taylor’s sons told her his mother was a ‘fake and a con woman.’ ”

Taylor used her charms to seduce Lamar Jones and her many other husbands. But her powers of persuasion worked on more than just marriageable men. Patricia Parks-Lee says her mother was trusting and naive. As a native of Trinidad, where there’s a long tradition of belief in sorcery and folk magic, she may have been more inclined than most to buy what Linda Taylor was selling. It seems likely that Taylor convinced Parks that she had spiritual skills—and convinced her, somehow, to hand over her children, her property, and access to her bank accounts. When Taylor was arrested for stealing a can opener and fur coat the year after Parks’ death, the dead woman’s credit card was among the items found in her possession.

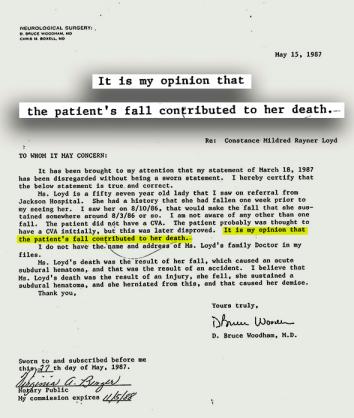

As in the Fronczak kidnapping, Taylor was never charged with killing Patricia Parks. James Piper, the prosecutor in the welfare fraud case, also looked into the alleged Parks homicide. He tells me that he “was satisfied personally that there had been chicanery.” But Piper says that he wasn’t able to acquire blood samples from the hospital where Parks had been pronounced dead. He believed that without the samples there was no “connector”—nothing to convince a jury that Taylor had administered a lethal drug cocktail to Parks. Piper says that his decision wouldn’t have prevented the Chicago police from continuing their investigation. He believed, though, that indicting Taylor for murder would have created the perception that he was looking for more publicity for the welfare fraud case—a case with clearer evidence, and one that he didn’t want to jeopardize.

For Jack Sherwin, this seemed backward. Despite his deep familiarity with Taylor’s criminal methods, Sherwin was never included in the Patricia Parks investigation—he says that would have required Chicago homicide cops to share their turf with a burglary detective, a nonstarter in the territorial department.

Other than Sherwin, nobody seemed all that motivated to learn the full extent of Linda Taylor’s crimes. Though the Tribune wrote about Taylor’s purported connections to the Fronczak kidnapping and the Parks homicide, the paper treated her kid-snatching and voodoo spells as colorful details—odd facts to embellish the shocking welfare queen story. In 1975, the Tribune reported the allegation that Linda Taylor was “buying newborn infants to substantiate welfare claims.” Somehow, though, the welfare claims remained the bigger story, not the allegations of black-market baby trafficking.

For Ronald Reagan, Taylor was a tool to convince voters that the government was in crisis. For Reagan’s detractors, she personified the candidate’s penchant for willful exaggeration. For Illinois politicians and prosecutors, the war against Linda Taylor and her ilk was a chance to vent some populist outrage and maybe launch a career. A murder in Chicago is mundane. A sumptuously attired woman stealing from John Q. Taxpayer is a menace, the kind of criminal who victimizes absolutely everyone.

In the 1970s, it was possible for the Tribune, the Sun-Times, and the Defender to make Linda Taylor a national figure while her specific exploits remained local knowledge. This is how, in the days before the Web abetted the flow of information, Ronald Reagan could tell stories about a real woman and be accused of conjuring a fictional character. And it’s how, after Taylor’s brief window of infamy closed, all the disturbing allegations that had been raised in the mid-1970s just faded away.

Patricia Parks-Lee says she thought that Taylor had been sentenced to 20 years behind bars, and that she’d taken comfort from that fact. In reality, the welfare queen was out of prison much sooner than that, and she had no trouble starting a new life, with a bushel of new names.

Taylor did not get Patricia Parks’ house or custody of her children. After their mother’s death, Parks-Lee and her brothers lived with their father and paternal grandparents. It took more than a year for things to get back to normal, Parks-Lee says, at least as normal as they could possibly be. She remembers finding picked-over food, bones, and seeds that one of her brothers had secreted away underneath his bed—a precaution against future deprivation. Her grandfather would assure the boys that they didn’t have to worry anymore, that “they could eat till they puked.”

As she says those words, Patricia Parks-Lee starts to cry. It’s still hard to talk about those days, and to think about the time when Linda Taylor came into her life and destroyed it before she could figure out what was happening. When I first reached out to her, Parks-Lee explains, she was suspicious. “I really thought you were working on her behalf,” she says. Now she has a mission for me: She wants me to track down Linda Taylor, and she wants me to report back that the welfare queen is dead.

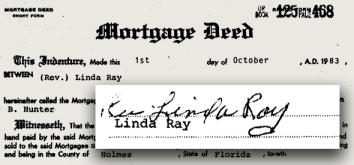

Taylor began serving time for welfare fraud on Feb. 16, 1978. Though Illinois corrections officials say her prison records have been lost, she was a free woman by 1983 at the latest. By the time Taylor won her release, she was closing in on 60 years old, and she was no longer the object of public fascination. When she became a widow in 1983, it didn’t make any headlines. Now, her name was Linda Ray.

Graphic by Slate

On Aug. 25, 1983, 63-year-old Willtrue Loyd shot and killed 35-year-old Sherman Ray in Momence, Ill., a small town 50 miles south of Chicago. When police arrived at the scene, Loyd confessed to pulling the trigger, explaining that he’d done the deed with the 12-gauge shotgun that was now propped against his trailer. Loyd told the cops that he’d been trying to kill a 7-foot snake that was meandering through his corn patch. All of a sudden, he said, Ray came up behind him and started grabbing at his gun. As they struggled, the firearm discharged inches from Ray’s chest. He was killed instantly.

Taylor had married Sherman Ray, a former Marine, before she landed in prison. Ray’s sister Patricia Dennis says her brother was caring, sincere, and hardworking. When he came back from Vietnam, though, Ray had “emotional problems.” His sister says he had flashbacks, and he’d become agitated if anyone touched him. Dennis, who’s 67 years old and lives in Arizona, says nobody in her family knew Linda Taylor—that she “came out of nowhere.”

Along with Sherman Ray, Taylor had another man by her side in Momence: Willtrue Loyd. Johnnie Harbaugh’s wife Carol, Taylor’s daughter-in-law, says Loyd was one of the nicest people she’s ever been around, the kind of guy who’d do anything for you. He was an older gentleman, a World War II veteran, and he was particularly devoted to Taylor—it was as though she had some kind of hold over him.

Johnnie and Carol say that Loyd and Ray were always scuffling, and that this mutual contempt was by design. They believe that Taylor pitted the two men against each other, then stepped back and watched the inevitable result. “Linda would never be present for anything that was happening or going on. Nothing could ever come back to her,” Carol says. “She was like a ghost.”

After making his confession, Loyd was handcuffed and put in a squad car. The next day, he was released due to lack of evidence. At an inquest into the circumstances of Ray’s death, a detective stated that four potential witnesses all told him they hadn’t seen what happened. One man said he’d been drinking with Ray that day, and a bottle of wine was found on the scene. According to a toxicology report, the victim’s blood ethanol count was an extraordinarily high 0.333.

In the aftermath of Ray’s death, the National Home Life Insurance Company requested a complete coroner’s report from Illinois’ Kankakee County. Byron Keith Lassiter, who looked into the case on behalf of the insurance firm, says such a contestable death claim investigation would have been routine. With no charges filed against Loyd, the money from Sherman Ray’s life insurance policy would be paid out to his wife, Linda.

Holmes County, Fla., Clerk of Court. Graphic by Slate.

A month after Sherman Ray’s death, Taylor bought a parcel of land in Holmes County, Fla. Her name is listed on the deed as “Rev. Linda Ray.” In the Sunshine State, public records reveal, she’d use at least six names and six different Social Security numbers. She wasn’t there alone. Her companion was her husband’s killer, Willtrue Loyd.

This is Linda Taylor’s life in microcosm: a series of tangled connections, a death that serves as a potential windfall, a quick move, and a new start in a faraway place. Sherman Ray, the former Marine with emotional problems, was a man in uniform—a classic Taylor mark. Paul Stull Harbaugh, the man listed as her son Paul’s father on the child’s birth certificate, was in the Navy. So was another supposed husband, Paul Steinberg—the Tribune alleged that in the 1960s she was “obtaining federal support” as the widow of both Harbaugh and Steinberg.

Lamar Jones, too, was in the Navy. He claims that when she filled out paperwork to become his dependent in 1974, Linda indicated that another of her husbands had been killed in Vietnam. Given her taste for military men, Jones’ first meeting with “Linda Sholvia” at Great Lakes Naval Training Center takes on a different cast. He thought he was lucky to find such a glamorous woman. It’s more likely that she found him—that Taylor saw something in the 21-year-old Jones that she thought she could exploit.

In 1978, one of her lawyers wrote that Linda Taylor was likely psychotic, that she “was incapable of knowing whether or not she was telling the truth.” Johnnie Harbaugh is certain that’s not the case. “She was cold,” he says. “She knew what was right and wrong, but she was choosing wrong.”

For Linda Taylor, people were consumable goods, objects to cultivate, manipulate, and discard. Once she’d extracted something of value—an identity, a check, a life insurance claim—she’d move on to someone else. No matter her circumstances, and no matter her surroundings, there was always a new target.

What kind of person behaves this way? In the 1970s, psychologist Robert Hare developed a checklist to assess a given subject’s personality. The symptoms on Hare’s list read like a catalog of Linda Taylor’s known behaviors and personal characteristics: glib and superficial charm, pathological lying, manipulativeness, lack of empathy, parasitic lifestyle, frequent short-term relationships, and criminal versatility.

Of the 20 items on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist–Revised, nearly every one describes the welfare queen to some degree. Dr. Steve Band, a behavioral science consultant and an expert on criminal behavior, says “people with that personality know right from wrong.” Dr. James Fallon, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the University of California at Irvine and the author of The Psychopath Inside, says that Taylor “screams psychopathy.” Along with deriving pleasure from criminal behavior, he says, psychopaths “really like getting away with it”—that “the ones who have intelligence, they don’t want to get caught.”

Despite the striking synchronicity between this checklist and Taylor’s behavior, diagnosing someone as a psychopath isn’t as easy as ticking a set of boxes. As Dave Cullen wrote for Slate in 2004, it took an elite group of mental health experts to establish Columbine shooter Eric Harris’ psychopathic “pattern of grandiosity, glibness, contempt, lack of empathy, and superiority.”

If a similar team of psychologists scrutinized the welfare queen, Hare’s checklist would be a logical place to start. For her part, Taylor’s daughter-in-law Carol Harbaugh has a simpler list, one with just three points: “She was brutal. She was mean. She was terrible.”

Some of Taylor’s victims were spared her worst behavior—they just learned an expensive lesson and got on with their lives. Kenneth Lynch, who’s now in his early 80s, bought a property with Taylor in Holmes County, Fla. Lynch remembers her saying that her husband had been killed by mobsters in Chicago. He also says that Taylor never came up with her share of the money, though she did pilfer Lynch’s last name. Reta Hunter, who lives in Live Oak, Fla., says “Linda Lynch” led her to stop trusting people. Taylor told Hunter she was a psychic who’d descended from Caribbean royalty, and that she could help remedy her relationship with her daughter. “The last time I seen her it cost me $80 for about 20 minutes,” Hunter says. “She could take you, honey. She was a slick talker.”

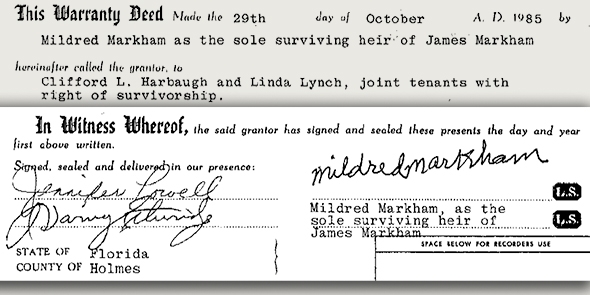

Not all of Linda Taylor’s relationships ended so harmlessly. Sherman Ray took a shotgun blast to the chest. Patricia Parks’ life ended in her daughter’s bedroom with her body pumped full of phenobarbital. And an elderly African-American woman named Mildred Markham died in Graceville, Fla., far away from her home and loved ones.

Taylor and Markham met in Chicago in the early 1980s. Markham’s husband James, a retired Pullman porter, earned a good salary in his day. Soon after he passed away, Taylor convinced the railroad man’s widow that she was her long-lost daughter. “All [Mildred] used to do was talk about this Linda,” recalls Markham’s granddaughter, Theresa Davis, who is 75 and still lives in Chicago.

By the time she fell under the sway of her new “daughter,” Mildred Markham was well into her 70s. Davis and her mother tried to convince Markham that Taylor was a con artist, but she wouldn’t listen. Markham went with Taylor to Momence, Ill. From there, they moved to Florida. All the while, according to Davis, “my grandfather’s money was going out the bank.” She says that as much as $50,000 went missing, along with Markham’s furniture, sewing machine, jewelry, and mink coats. And in 1985, Mildred deeded away 185 acres of Markham family land in Mississippi. The grantees were Linda Lynch and her son Clifford. For his part, Clifford says he had no idea that his name was on the deed, and that he played no part in this land deal.

Lincoln County, Miss., Chancery Clerk

Davis says she and her mother eventually saw evidence of their worst fears: Markham wrote them from Florida saying, without getting into specifics, that she was being mistreated. They tried to find Mildred, but all the addresses on her letters turned out to be phony.

Johnnie and Carol Harbaugh say they saw that abuse firsthand. Johnnie worked as a trucker back then, and he and his wife would see Taylor two or three times a year. She was living on a farm in Graceville, Fla., along with Willtrue Loyd and Mildred Markham.

Once, when the Harbaughs were in Florida for a visit, Markham begged them to take her back to Chicago. Carol says Taylor was verbally abusive, and that she watched her lock Markham in a room. Markham also told them that she wasn’t being fed. “She was forced to be there against her will,” Carol says.

They did not rescue Mildred Markham. Johnnie says that he was determined to take her but that she changed her mind at the last minute and decided to stay. In Carol's recollection, Taylor told Johnnie, “You even think about it, and I’ll blow your head off.” She says her husband took the threat seriously, and he decided not to get involved.

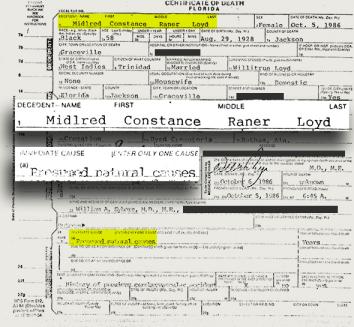

Mildred Markham died on Oct. 5, 1986. Her death certificate says she passed away of “presumed natural causes,” and that she had previously suffered a stroke. The Graceville police department reported that her husband, Willtrue Loyd, found her body in bed.

Carol Harbaugh says she thought Loyd and Markham had gotten married. Florida records suggest that was probably the case. In March 1986, Loyd married a woman named “Constance Rayner” in Marianna, Fla. The marriage application says Constance’s home state is Louisiana; Theresa Davis says that’s where her grandmother, Mildred Markham, was born. The bride signed her supposed maiden name, Constance Wakefield, in a looping script. It’s a shaky signature, one that doesn’t much resemble Linda Taylor’s tidy penmanship.

Florida Medical Examiner, District 14. Graphic by Slate.

Taylor always took something from her prey. But this marriage record, with the telltale Wakefield surname, shows that even as she sucked this older woman dry, Taylor was grafting parts of herself onto Mildred Markham.

Markham’s medical examiner’s file lists her name as Mildred Constance Raner Loyd. Her death certificate (which misspells her first name) indicates that she’s a citizen of Trinidad, and her parents’ names are Frank Raner and Edith Wakefield. According to her granddaughter, Mildred Markham’s maiden name was actually Hampton, and she was born in the United States. Markham’s mother was not Edith Wakefield—back in the 1960s, Linda had tried to convince a judge that Edith Jarvis Wakefield was her own mother. When Markham was still alive, Taylor made her believe that they were mother and daughter. In death, she slotted Markham into her long-running, fictional life story.

As in the cases of Patricia Parks and Sherman Ray, Taylor stood to gain financially from Mildred Markham’s death. Mildred’s medical examiner’s file includes letters from Union Fidelity Life Insurance and Gulf Life Insurance, both of which were looking to verify the claims of one “Linda Lynch,” the decedent’s daughter. The file also contains a note in which someone, presumably the medical examiner’s assistant, writes that Markham’s daughter “took out insurance policies at varied times using different names (marriages).” The daughter needed a letter to clear up this misunderstanding, and the medical examiner complied. “To the best of my knowledge Mildred Constance Raner Loyd, Constance Loyd, and Mildred Rayner are one in the same person,” he wrote.

Florida Medical Examiner, District 14. Graphic by Slate.