Excerpted from Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air by Richard Holmes, out now from Pantheon.

On April 19, 1861, just as the drums of war had begun to sound in Washington, Thaddeus Lowe launched his small, businesslike balloon the Enterprise from a vacant lot in the heart of Cincinnati. Lowe’s ambitious plan was to fly 500 miles due east over the Allegheny Mountains, and to land in Washington, ideally perhaps on the front lawn of President Lincoln’s White House. Here he might offer his services to the Union cause, and outflank rival aeronauts who hoped to do the same. In the event, he met a rebel breeze, and ended up much farther south, having skirted Kentucky and Tennessee, and finally touching down after 650 miles near Unionville in the heart of the seceded state of South Carolina.

On landing, Lowe found the Civil War already declared and decidedly in progress. The local cotton farmers were not impressed by his flying skills or his Yankee accent. On the contrary, he was arrested as a spy for supposedly carrying dispatches from the Union North, blatantly piled in the corner of his balloon basket. With some difficulty, due to local illiteracy, he was able to demonstrate that these dispatches were actually a special balloon edition of the Cincinnati Daily Commerce, and thereby escape being lynched.

Lowe and his balloon were packed off unceremoniously on a coach back west. Once safe in Kentucky, which had not seceded to the South, he switched to the railroad and hurried north to Washington, with his balloon and basket in packing cases. Here the news was that the Union Army of the Potomac was preparing to invade rebel Virginia, and was already skirmishing across the Potomac River near Arlington. Its new commander, Gen. George C. McClellan, like a good Yankee, was in principle sympathetic to advanced technology. Provided it was securely tethered, the Enterprise could carry up telegraph equipment and a wire, and send direct aerial observations to a commander on the ground. Lowe demanded to demonstrate this to Lincoln himself as a matter of acute urgency.

It says a great deal about Lowe that, amid all the administrative chaos of a newly declared war, he achieved exactly this. On Sunday, June 16, 1861, Lowe ascended in his balloon some 500 feet above Constitution Mall, Washington, with a telegraph key and an enthusiastic Morse operator. The telegraph wire was strapped to the tether line and winch, and then run directly across the lawn and into a service room in the White House. Lowe transmitted the following message:

Balloon Enterprise. Washington, D.C. 16 June 1861

To President United States:

This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station and in acknowledging indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the service of the country. T.S.C. Lowe

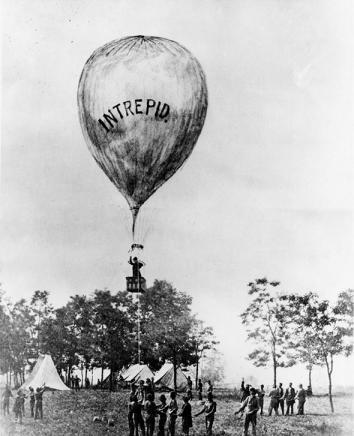

In this dramatic fashion, Lowe succeeded in persuading Lincoln to allow him to form an official Military Aeronautics Corps within the Union Army. Lowe finally received Union funds to build further balloons in August 1861. His fleet eventually consisted of no fewer than eight military aerostats: the Union, the Intrepid, the Constitution, the United States, the Washington, the Eagle, the Excelsior, and the original Enterprise. The new balloons could carry enough tether and telegraph cable to climb to 5,000 feet.

On Sept. 24, Lowe ascended in the Union to more than a thousand feet near Arlington, across the Potomac River from Washington, and began telegraphing intelligence on the Confederate troops located at Falls Church, Va., more than 3 miles away. Union guns were then calibrated and fired accurately on these enemy dispositions without actually being able to see them. This was an ominous first in the history of warfare, by which destruction could be delivered to a distant and invisible enemy.

* * *

For the rest of 1862, it was Lowe’s Union Balloon Corps that operated exclusively during the Virginia phase of the Civil War.

Lowe’s balloons were present at the siege of Yorktown in May 1862; at the Battle of Fair Oaks in May–June 1862; at the crucial Seven Days Battle outside Richmond in June–July 1862; and at the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. He also witnessed the famous rebel victory by Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville in May 1863.

From his balloons, Lowe witnessed a new kind of American fighting. Rapid, violent, passionate, and patriotic (on both sides), it was based on a swift exchange of attack and counterattack. There were long days of immobility and siege, especially at Yorktown. But most characteristic was the constant maneuvering of infantry and artillery across open countryside checkered with small townships, manufactories, farmsteads, mills, river bridges, and railway junctions, any one of which could suddenly become a strategic key point, where thousands might die. Speed, and often dissimulation, were vital factors. Military intelligence—the knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions, troop numbers, firepower, potential reinforcements, and above all its unexpected movements and hidden intentions—was paramount. Lowe always believed that balloons could supply this.

What Lowe observed was a new kind of infantry war, with great tides of men and metal constantly clashing. It produced casualty figures never before seen in American history.

Yet Lowe rarely described the human details of what he saw. Instead, he confined himself to tactical reporting, like someone observing the moves in a vast, impersonal game of chess. But the unmistakable sounds of war came up to him—the boom of shells, the rattle of shots, the screaming of wounded. He wrote: “It was one of the greatest strains upon my nerves that I ever have experienced, to observe for many hours a fierce battle.”

Photo courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution Archives

Lowe was always active and adaptable. His balloons were brought into action from horse-drawn carts, from railroad wagons, and even from the decks of boats. At one stage he operated a tethered observation balloon from a coal barge, the Rotary, sailing up and down the Potomac River. He afterward claimed it was the first “aircraft carrier” —although his rival John LaMountain had done the same thing on the James River. He was prepared to inflate his balloons from coal-gas mains, hydrogen field generators, or cobbled-together barrels of sulfuric acid and metal shell casings. On one emergency occasion, he even used another balloon, “transfusing” the gas from his small Constitution via a makeshift valve (“contrived from a convenient kettle”) into the larger Intrepid.

Lowe himself had no doubts as to the impact of his Balloon Corps in the early months of the Peninsula Campaign. As he put it graphically: “A hawk hovering above a chicken yard could not have caused more commotion than did my balloons when they appeared before Yorktown.” Rebel sources seemed to agree: “At Yorktown, when almost daily ascensions were made, our camp, batteries, field works and all defenses were plain to the vision of the occupants of the balloons. … The balloon ascensions excited us more than all the outpost attacks. … ”

Military observation with binoculars was a delicate art. A tethered balloon was rarely stable—at 500 feet in any kind of wind, Lowe found the balloon “very unsteady, so much so that it was difficult to fix my sight on any particular object.” At a thousand feet he could see 12 miles and a whole battlefield, yet always “indistinctly” because of the dust, smoke, and heat haze produced by masses of troops on the move. Even more, the heavy silver-gray smoke produced by field guns in action might temporarily block out the ground altogether.

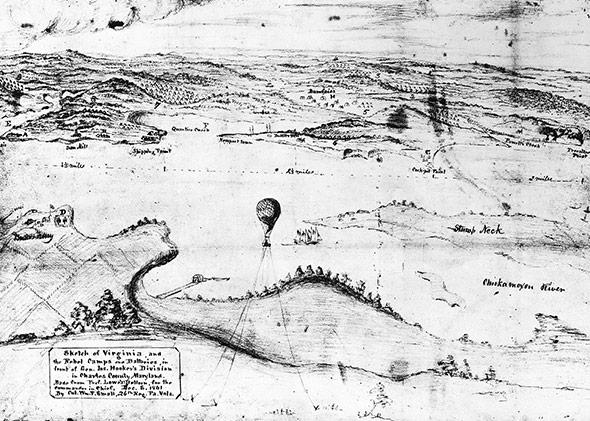

Lowe communicated his observations by various means. Ideally, he used a telegraph key operated from his balloon basket, transmitting messages down a 5,000-foot telegraph cable directly to McClellan’s headquarters. But bad conditions often made this impossible—the equipment could be too heavy to take aloft, or the cable could break. In that case Lowe would make notes and drop them in canisters to a telegraph operator on the ground. He did the same with rapidly drawn sketch maps of the enemy positions, which were then delivered to McClellan by runner. On other occasions he used signal flags, colored flares or simply hand-gestures. If all else failed, he would have himself winched down so he could deliver his observations in person, sometimes galloping to the headquarters on his favorite gray mare, a procedure he apparently enjoyed.

Lowe had promised to supply McClellan with strategic aerial photographs, which he said could be examined by giant magnifying glasses once delivered to the ground. He claimed optimistically that a 3-inch-square glass negative would provide the equivalent of a “20 foot panoramic image” of a battlefield. He took aloft several professional photographers—“[Matthew] Brady the celebrated War photographer was also much interested in the work of the Corps, and spent much time with us.” Yet no such aerial photographs have survived. While there are thousands of Civil War photographs taken on the ground, there is not a single known photograph of a Civil War battlefield taken from a balloon. Probably cameras, glass negatives and chemical developing equipment proved too cumbersome for the tiny observation baskets. Or perhaps the whole process was simply too slow to be of any practical use. Timing was vital, because what Lowe had discovered was the highly mobile nature of battlefield observation. This transformed the traditional idea of the tranquil, all-seeing “angel’s-eye view” from a balloon. In warfare, the panoptic vision no longer provided the classic, unfolding “map” of the world beneath. Instead it revealed a constantly moving game-pattern, a shifting topography of hints and clues, secrets and disguises, threats and opportunities. An entire tactical situation could change within a matter of hours, or even minutes.

Visual clues had to be carefully sought out: smoke from campfires, rising road dust, sun glinting on armory, newly dug patches of raw earth, the straight lines of fresh infantry trenches, the faint dimpled shadows of breastworks, the regular white circles of bell tents, the deep curving tracks left by heavy guns. Lowe writes on one occasion of taking a general “to an altitude that enabled us to look into the windows of the city of Richmond.” The battle landscape had to be read constantly, interpreted shrewdly, and summarized with the utmost speed.

One of Lowe’s most brilliant observational coups was the discovery of the Confederates’ secret evacuation of Yorktown, under the cover of darkness, on the night of May 4–5, 1862. This gave the Union Army one of its most crucial tactical advantages in the whole Peninsula Campaign. At the time it was thought that Yorktown was being resupplied, and stiffening its defenses against the Union’s long siege. Lowe’s account is vivid, and turns on a single, precisely observed detail. First of all he sets the scene: “The entire great fortress was ablaze with bonfires, and the greatest activity prevailed, which was not visible except from the balloon. At first the General [Samuel P. Heintzelman] was puzzled on seeing more wagons entering the forts than were going out.”

This was apparently clear evidence of resupplying. Lowe, however, observed and interpreted more carefully: “But when I called his attention to the fact that the ingoing wagons were light and moved rapidly (the wheels being visible as they passed each campfire), while the outgoing wagons were heavily loaded and moved slowly, there was no longer any doubt as to the object of the Confederates. They were withdrawing.”

According to Lowe, his observations of this secret evacuation carried instant conviction to the highest command level: “General Heintzelman then accompanied me to General McClellan’s headquarters for a consultation, while I with the orderlies, aroused other quietly sleeping corps commanders in time to put our whole army in motion in the very early hours of the morning, so that we were enabled to overtake the Confederate Army at Williamsburg.” The result was one of the few decisive victories of the Union Army of the Potomac, which was otherwise becoming characterized by its lack of decision and initiative. By the end of May, McClellan was within 5 miles of Richmond.

—

Excerpted from Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air by Richard Holmes, out now from Pantheon.