One hundred years ago today, in a courtroom in Kiev, then part of the Russian Empire, the most famous accused murderer on Earth rose to declare, “I am innocent.” Mendel Beilis, a 39-year-old father of five, had spent more than two years in squalid prison cells waiting to say those words. The Russian and world press had been waiting, as well, to cover one of the most bizarre cases ever tried in an ostensibly civilized society. The Russian state had charged Beilis, a Jew, with the ritual religious killing of a Christian child to drain his blood for the baking of Passover matzo.

Beilis’ 34-day trial in the fall of 1913 made international headlines. The frame-up of an innocent man on a charge seemingly out of the Dark Ages provoked widespread indignation and drew the attention some of the era’s greatest personages. Leading cultural, political and religious figures such as Thomas Mann, H. G. Wells, Anatole France, Arthur Conan Doyle, and the Archbishop of Canterbury rallied to Beilis’ defense. In America, the Beilis case made for inspiring collaboration between Jews and non-Jews. Rallies headlined by the likes of social reformer Jane Addams and Booker T. Washington drew thousands. The New York Times headlined an editorial “The Czar on Trial.”

The blood libel—the notion that Jews commit ritual murder to obtain Christian blood, generally the blood of children—originated in Western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. The historian Anthony Julius has called the blood libel the “master libel” against the Jews. It directly inspired the rampant metaphor of the Jews as economic “bloodsuckers.” More subtly, it underlies the slander of the Jews as a disloyal, conspiratorial, and parasitical force that exploits its hosts, sucking society’s energy.

It has been a remarkably persistent infection, sometimes lying dormant for decades, then erupting violently. In the latter decades of the 19th century, the blood libel experienced a rather mysterious revival in Central Europe, with upward of 100 significant cases in which specific allegations of ritual murder were made to the authorities or at least gained wide popular currency. Most of the cases were in Germany and Austria-Hungary. The accusations resulted in a half-dozen full-fledged ritual murder trials, some of which sparked anti-Semitic riots. (With the exception of an ambiguous case in Bohemia—in which the defendant was convicted, but the state officially rejected the ritual motive—all the suspects were acquitted.) Historians have reached no consensus on the precise causes of this phenomenon. But the wave was undoubtedly linked to the rise of modern anti-Semitism that culminated in some of the worst horrors of the 20th century.

The Beilis case was the last blood libel trial in Europe, and the only one to be fully backed by a central government (the others were primarily local affairs). I first heard of it as a boy from my Russian Jewish grandmother, who would recount tales of the old country around the dinner table, including the Jews’ persecution under the regime of Tsar Nicholas II. Many years later, moved by that memory to learn more about the case, I was surprised to find that it had been strangely neglected by historians. Bernard Malamud, inspired by its power, used it as the basis for his Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winning 1967 novel, The Fixer. Otherwise, little had been written about it, with the only book in English published nearly a half century ago.

The victim in the case, 13-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky, was found in March 1911, in a cave on the city’s desolate outskirts. He had been stabbed some four dozen times. Within days of the discovery of the body, the Russian anti-Semites known as the Black Hundreds began leveling the blood libel. A leaflet passed out at the boy’s funeral read: “The Yids have tortured Andrusha Yushchinsky to death!” A few months later, a troop of police and gendarmes dragged Beilis from his home in the middle of the night. There was no evidence against him, but he worked at a brick factory just a few hundred yards from where the body was found, so if a Jew was to be charged with ritual murder, he was the most convenient choice.

In its judicial procedures, Russia emulated the West, with the full apparatus of courts, judges, and juries. To prove the charge of ritual murder, the prosecution had to produce witnesses and expert testimony. Among those presented to the jury were: a pathologist who was paid a 4,000-ruble bribe from the tsar’s secret fund; a couple who, plied with alcohol by an investigator, gave wildly inconsistent accounts, recanted them when they sobered up, but were put on the stand anyway, where they rambled incoherently; a drunken derelict who could barely find the witness stand and, when she did, denied knowing anything; a Catholic priest and sometime con man from Tashkent who testified to the reality of the blood ritual, but was exposed as risibly ignorant of Jewish texts. But the most sensational witness was the dark diva of the Beilis affair, Vera Cheberyak, the leader of a criminal gang in Kiev that the police believed was responsible for scores of robberies. A few years earlier she had blinded her young French musician lover by throwing sulfuric acid in his face. (He refused to testify against her and they remained friendly after her acquittal.) She was the likely mastermind behind the murder of Andrei, who was her son’s best friend, in revenge for his suspected betrayal of her criminal activity to the police. She was widely believed to have killed her own son to keep him quiet about her role in the boy’s killing. Astonishingly, she ended up as a star witness for the state against Mendel Beilis.

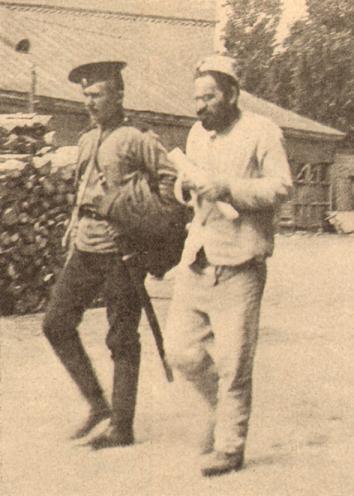

Photo courtesy of Edmund Levin

Tsarist officials were fully aware of the patent weakness of the case—in their secret communications they were quite candid on this point. By the end of the trial, the state had devised an ingenious insurance policy against an unthinkable failure to convict. The issue of ritual murder would be separated from the guilt of the defendant. The jury would be asked to decide two questions. First, did it accept the prosecution’s description of the crime as having been committed at the Jewish-owned brick factory, with the wounds resulting “in the almost complete loss of blood”? The words “ritual murder” were not used, but the implication was clear: the crime had all the hallmarks of the bloody Jewish rite. Second, was the defendant, Mendel Beilis, guiltyhere the language was explicit—of committing the crime “out of motives of religious fanaticism”?

Most courtroom observers, including Beilis’ own lead attorney, Oscar Gruzenberg, believed the mostly peasant jury—“exceptionally ignorant,” he called it—would vote with the prosecution on both questions. But the state’s insurance policy against an acquittal came into play. The jury voted yes on the first question—the crime had happened as the state had described it—but found Beilis not guilty of the crime. “The little peasants—they stood up for themselves!” a joyously surprised Gruzenberg said after the trial. Beilis had won his freedom, but the ambiguous double verdict allowed both sides to claim victory.

In the decades after his trial, Mendel Beilis—who moved to America and died in New York in 1934—was reliably mentioned in any anti-Semitic tract on Jewish ritual murder. The case surely helped the myth maintain its vitality. In 1926, the official newspaper of Germany’s rising Nazi Party, Volkischer Beobachter, devoted a six-part series to the Beilis affair, calling it a “test of strength between the Russian state and people and the Jews.” In the 1930s, Julius Streicher, editor of the infamous Nazi weekly Der Sturmer, energetically propagandized for the ritual murder charge, devoting special issues to the subject that listed Beilis in the pantheon of Jewish child-killers. The Nazi regime itself, it is true, never adopted the blood libel as a major part of its official propaganda. But in May 1943, the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, sent several hundred copies of a book on Jewish ritual murder, which included an entire chapter on the Beilis trial, for distribution to the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile death squads that killed more than 1 million Jews in Eastern Europe. The tomes, Himmler explained to a top lieutenant, were important reading “above all to the men who are busy with the Jewish question.”

During World War II, there were signs that the Kiev case had survived in the collective memory. Residents of German-occupied Poland called the product rumored to be made from human fat in the Auschwitz concentration camp “Beilis Soap.” After the war, in Poland, as the historian Jan T. Gross has documented in horrifying detail, hundreds of Jews who had managed to survive German extermination were killed in pogroms. In many cases, the violence was sparked by rumors of ritual murder. The most notorious postwar pogrom in Poland took place on July 4, 1946, in the town of Kielce, where a mob killed 42 Jews and left some 80 wounded. A Jewish delegation attempted to secure a statement condemning anti-Semitism from the Bishop of Lublin, Stefan Wyszinski, later named a cardinal and primate of Poland. Wyszinski, according to a record of the meeting, declined to issue a special condemnation of anti-Semitism in connection with the blood libel, given that “during the Beilis trial the matter … was not definitively settled.”

A century after the trial, the Beilis case remains a rallying point for the extreme right fringe in Russia and Ukraine, with Andrei Yushchinsky’s gravesite a place of pilgrimage for far-right true believers. It would be a mistake, however, to exaggerate the extent of anti-Semitism in that part of the world. In the Middle East, where the bloodsucking Jew is a common trope, the blood libel has been featured in major newspapers such as Egypt’s Al-Ahram and been the subject of a book by a Syrian government minister. Of course, if the last century has taught us anything, it is that societies that consider themselves “enlightened” need especially to be on their guard against irrational hatred. The ordeal of Mendel Beilis stands as a cautionary reminder of the power and persistence of a murderous lie.

This article is adapted in part from Edmund Levin’s forthcoming book, A Child of Christian Blood—Murder and Conspiracy in Tsarist Russia: The Beilis Blood Libel, to be published in February 2014 by Schocken Books.