On March 8, 1971, a handful of activists broke into the FBI’s field office in Media, Penn., and made off with a stack of incriminating documents. Over the next several months, they began to publish what they had learned. In the pre-Internet age, this often meant reprinting the FBI records in the alternative press, though papers such as the Washington Post and New York Times also picked them up. Like Glenn Greenwald’s recent revelations about the NSA, the discoveries from the Media break-in sparked widespread public outrage—and turned out to be one of the biggest scoops in intelligence history.

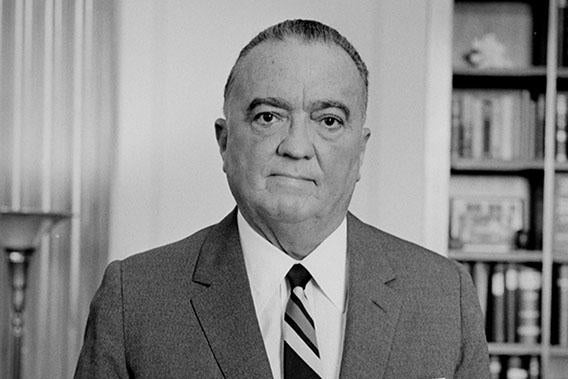

The program they exposed was called COINTELPRO (short for “counterintelligence program”), known today as the most notorious of the many notorious secret operations authorized by former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Under COINTELPRO, federal agents engaged in a jaw-dropping array of abuses—not only widespread surveillance of law-abiding American citizens, but also active “disruption” efforts against political organizations and activist leaders. The most famous is perhaps the FBI’s bugging of Martin Luther King’s hotel rooms, an effort that captured King in a variety of sexually compromising situations. When the press refused to peddle the sex stories (yes, the press used to refuse to peddle sex stories), the FBI sent King an anonymous note urging him to drop out of politics, and potentially to commit suicide. “You are done,” the letter declared. “There is but one way out for you.”

There can be no question that COINTELPRO was more intrusive—if also more targeted—than today’s apparent efforts at mass technological surveillance by the National Security Agency. But there is at least one important distinction that makes today’s scandal far more disturbing. When the FBI launched COINTELPRO, it was acting alone, outside of the boundaries of established law. Today, what the NSA is doing appears to be legal—and nearly every branch of the government is complicit. Unlike Hoover’s activities, the NSA’s programs come to us with the seal of congressional and judicial approval. It didn’t take J. Edgar Hoover to engineer this scandal. We did it to ourselves.

* * *

From his earliest days as FBI director, Hoover had shown a talent for skirting the law. When Franklin Roosevelt encouraged him to look into domestic fascist and communist movements in the late 1930s, Hoover took this as a secret mandate to launch mass intelligence operations. When Congress outlawed wiretapping that same decade, Hoover interpreted the new statute to mean that he should not disclose wiretap evidence in court—then continued to wiretap as part of his ongoing intelligence operations. For Hoover, the sanctity and secrecy of FBI records was always the top concern; if it seemed that a secret program might be exposed, he often tried to shut it down. In at least one case, he allowed a known Soviet spy to walk free rather than take the risk that he would be forced to produce raw FBI reports in front of a jury of citizens.

Such secrecy was arguably easier to maintain in the 1950s and 1960s for a simple reason: Outside of appropriations hearings, intelligence agencies were not subject to much congressional oversight. Theoretically, Hoover worked for the attorney general, who worked for the president, and FBI policies were approved up the chain of command. In reality, he worked for himself and did mostly what he wanted. This is not to say that Hoover was a rogue actor, engaged in activities that would have horrified his Washington contemporaries. Rather, most politicians understood the deal: The FBI might be up to no good, but it was in the interests of national security, and it was best not to ask too many questions.

As a result, most efforts to expose the FBI’s operations came from outside of Washington, and from outside the mainstream press. 1960s activists had been complaining for years that the FBI was bugging their meetings, planting informers, disrupting their relationships and organizations. But until the Media break-in they had little by way of hard proof. In that sense, the Media revelations—like the ongoing NSA scandal—were less about shock and surprise than about confirmation: The government was in fact doing everything you already sort of knew it was doing. After the Media burglary, COINTELPRO entered the popular lexicon as the shorthand designation for an entire universe of government surveillance, lies, and betrayal. PRISM may now take on a similar life, a one-word reminder that the government may, in fact, be watching your keystrokes.

The FBI responded to the Media break-in by circling the wagons. Hoover cut back on counterintelligence activities, punished the local office chiefs, and set about trying to catch the burglars. But he had little luck. The Media burglary—“Medburg,” in the FBI’s lexicon—still ranks as one of the Bureau’s great unsolved cases.

The political consequences were severe, however, and took several years to play out. In October 1971, a group of prominent civil liberties activists gathered at Princeton University for a conference to pressure the government into enacting intelligence oversight and reform. But it was not until 1975, in the wake of Watergate, that Congress itself took action. That year Idaho Sen. Frank Church led a sweeping congressional investigation into intelligence abuses, one the most expansive such efforts in American history.

What he found confirmed the revelations from Media and then some, exposing COINTELPRO as a program that swept in groups from the Weathermen to the Ku Klux Klan. Hoover himself had died by that point, and he made an easy scapegoat, a larger-than-life figure who had amassed more power than any single man deserved, and who had used it to make a mockery of American democratic tradition. The discoveries went well beyond Hoover, though, and well beyond the FBI. According to the Church Committee reports, every federal intelligence agency had engaged in widespread civil liberties abuses over the previous 30 years, beginning with mass surveillance of domestic political groups and moving on up through the assassination of foreign leaders.

The result was a new system of oversight—institutions like the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the FISA courts that govern intelligence activities today. When they were created, these new mechanisms were supposed to stop the kinds of abuses that men like Hoover had engineered. Instead, it now looks as if they have come to function as rubber stamps for the expansive ambitions of the intelligence community. J. Edgar Hoover no longer rules Washington, but it turns out we didn’t need him anyway.