The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a firm view on homosexuality and gay marriage. “Marriage between a man and a woman is essential to the Creator’s plan,” the church declares on its website. “The Church’s doctrinal position is clear: Sexual activity should only occur between a man and a woman who are married.”

But there’s a catch: LDS doctrine is subject to sudden reversals. While other churches cling to the Bible, Mormons believe new revelations can overthrow past injunctions, including those written in Scripture. “Nowhere does the Bible proclaim that all revelations from God would be gathered into a single volume to be forever closed,” the church contends.

In fact, Mormons have been revising their doctrines all along. The revisions are driven by cultural and political changes, though the church attributes them to revelation. This is the pattern in a series of essays, posted on the church’s website, that explains its evolution on difficult issues. The pattern suggests that eventually the church might do the same with homosexuality.

Three of the essays focus on polygamy. They claim that this practice entered the church in the 1830s and 1840s through revelation (LDS founder Joseph Smith and his contemporaries experienced visions) and exited the church half a century later in the same way. But the exit was gradual. Mormon leaders didn’t see the light till they felt the heat. Beginning in 1882, the U.S. government outlawed polygamy, jailed church officials, and confiscated church property. In 1890, the Supreme Court upheld the confiscations. That’s when revelation struck the church’s president, Wilford Woodruff:

President Woodruff saw that the Church’s temples and its ordinances were now at risk. Burdened by this threat, he prayed intensely over the matter. “The Lord showed me by vision and revelation,” he later said, “exactly what would take place if we did not stop this practice,” referring to plural marriage. “All the temples [would] go out of our hands.” God “has told me exactly what to do, and what the result would be if we did not do it.”

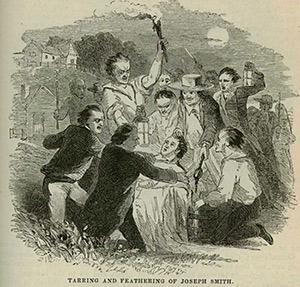

Courtesy of Harper’s Magazine/Creative Commons

Woodruff issued a manifesto pledging that the church would no longer sanction polygamy. But the practice persisted in some quarters, and Americans didn’t like it. In 1899, Congress, backed by 7 million petition signatures, refused to seat a polygamous Mormon who had been elected to the House. Several years later, the election of an LDS apostle to the Senate prompted that chamber to convene hearings. Meanwhile, the composition of the church’s leadership was changing. According to one of the church’s essays:

The time was right for a change in this understanding. A majority of Mormon marriages had always been monogamous, and a shift toward monogamy as the only approved form had long been underway. In 1889, a lifelong monogamist was called to the Quorum of the Twelve; after 1897, every new Apostle called into the Twelve, with one exception, was a monogamist at the time of his appointment.

A month after being hauled before the Senate, the church’s new president issued a statement threatening to excommunicate anyone who performed or entered into a polygamous marriage. This, the essay explains, was the culmination of “a process rather than a single event. Revelation came ‘line upon line.’ ”

The church’s racial views evolved in a similar way. Beginning in 1852, it prohibited blacks of African descent from becoming priests or marrying in temples. Its essay on this topic argues that Mormons were influenced by the surrounding culture of slavery and segregation. As American segregation began to erode in the 1940s and 1950s, the church relaxed its rules, extending the priesthood to Australian Aborigines. But the policy against Africans continued.

Eventually, two other developments forced a change. One was a marketing problem. The essay says the policy “created significant barriers” for evangelism as the church “spread in international locations with diverse and mixed racial heritages.” The other shift was emotional:

In 1975, the Church announced that a temple would be built in São Paulo, Brazil. As the temple construction proceeded, Church authorities encountered faithful black and mixed-ancestry Mormons who had contributed financially and in other ways to the building of the São Paulo temple, a sanctuary they realized they would not be allowed to enter once it was completed. Their sacrifices, as well as the conversions of thousands of Nigerians and Ghanaians in the 1960s and early 1970s, moved Church leaders.

In secular circles, this is known as contact theory. Working with unfamiliar people—blacks, gays, Muslims, Koreans—helps you get past your stereotypes and recognize each person’s humanity. But to change the policy, Mormons needed a revelation. So they had one:

In June 1978, after ‘spending many hours in the Upper Room of the [Salt Lake] Temple supplicating the Lord for divine guidance,’ Church President Spencer W. Kimball, his counselors in the First Presidency, and members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles received a revelation. … Gordon B. Hinckley, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, remembered it this way: “There was a hallowed and sanctified atmosphere in the room. For me, it felt as if a conduit opened between the heavenly throne and the kneeling, pleading prophet of God who was joined by his Brethren.”

With that, the policy ended.

When you look back at these stories—not just the reported facts, but the way the church has recast them—you can see how a reversal on homosexuality might unfold. First there’s a shift in the surrounding culture. Then there’s political and legal pressure. Meanwhile, LDS leaders have to grapple with the pain of gay Mormons—now acknowledged by the church as “same-sex attracted”—who sacrifice for an institution that forbids them to love and marry. Within the church hierarchy, less conservative voices gradually replace leaders who have died or stepped down. Eventually, the time is right for a revelation. When you pray hard enough, and you know what you want to hear, you’ll hear it.

The church is well along this path. Two years ago, it acknowledged homosexuality as a deeply ingrained condition and said it “should not be viewed as a disease.” Today, in its essay on polygamy, the church affirms its defense of traditional marriage, but with a caveat. “Marriage between one man and one woman is God’s standard for marriage,” the essay concludes—“unless He declares otherwise, which He did through His prophet, Joseph Smith.” It happened once. In fact, it happened twice. When the time is right, it’ll happen again.