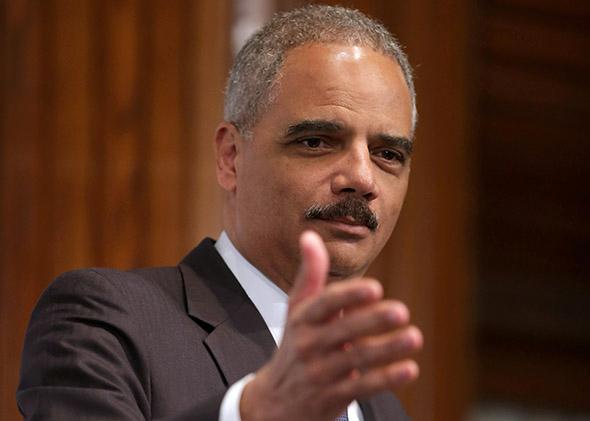

This weekend, on the 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board, Attorney General Eric Holder delivered an important speech on race and inequality. He emphasized the persistence and power of social stratification, compared with the superficiality of racist remarks by Cliven Bundy and Donald Sterling. Holder called for an “honest, tough, and vigorous debate,” setting aside simplistic answers and instead speaking “forthrightly about these difficult issues.”

Those are good ground rules. One thing they ought to inspire is a clear-eyed sorting of the issues Holder discussed. When we talk about prejudice, discrimination, and inequality, we’re talking about related but different things. The further we advance toward rectifying discrimination, and the harder we push, the more difficult the issues become.

Holder, speaking to graduates at Morgan State University, recalled the history of American racism. First came slavery: “those who built this nation while it held them in chains.” Then “overtly discriminatory statutes like the ‘separate but equal’ laws of 60 years ago,” under which Holder’s father “was denied service at a lunch counter and told to leave a whites-only train car.” Then policies that were officially neutral but affected whites and minorities differently, such as strict voter identification laws.

In the latter category, Holder mentioned various disparate-impact practices. He didn’t classify them, but I’ll try. The first group, represented by the voter ID laws, includes policies that are objective in form but tainted by biased intent. The ID restrictions are “justified as attempts to curb an epidemic of voter fraud that in reality has never been shown to exist,” said Holder. In practice, “these policies disproportionately disenfranchise” blacks and Latinos. The motive isn’t directly racial, but it’s certainly about limiting the influence of known Democratic voting blocs, which amounts to the same thing. Holder implied that the effects were deliberate: “Interfering with or depriving a person of the right to vote should never be a political aim.”

Another class of disparate-impact practices consists of subjective applications of law, which allow race to directly, if unconsciously, influence differences in outcome. In Holder’s speech, the clearest case was criminal sentencing. He cited a study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which found that black men “have received sentences that are nearly 20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes.”

Then there’s a third class of disparate-impact policies: those that exacerbate racial gaps even when they’re objectively designed and applied. In this category, Holder cited “zero-tolerance school discipline practices that, while well-intentioned and aimed at promoting school safety, affect black males at a rate three times higher than their white peers.”

Holder added one more charge to the indictment: “the quiet prejudice of inaction—and the cold silence of consent.” This phrase covers tolerance of inequality, regardless of its causes.

These four categories, plus the original two (slavery and Jim Crow), don’t exhaust the full range of racially problematic practices. A more complete list might distinguish discrimination by law, direct discrimination in public accommodations, indirect discrimination in public accommodations, economic segregation, cultural segregation, overt expressions of prejudice, and covert expressions of prejudice. One upshot, no matter how you draw up the list, is that as you advance from the original to the more advanced problems—from law to culture, from bias to sincere neutrality, from direct racial effects to indirect racial effects, from commission to omission—the remedies and ethics become more complex. The injustice of zero tolerance in schools isn’t nearly as clear as the injustice of housing discrimination.

Implicitly, Holder acknowledged this in several ways. First, he tailored his language. Many people apply the word racism to all the practices mentioned above. Holder didn’t. He used the word only once, to refer (not by name) to the views of people like Sterling and Bundy. He reserved the term bigotry for the same class of offenses. For the more complex cases, he preferred the terms racial inequality and equal opportunity.

Second, he underscored the difficulty of recognizing indirect discrimination. He worried that many disparate-impact policies, which “have the appearance of being race-neutral,” are “more subtle” and “less obvious” than hateful outbursts “we can reject out of hand.” Holder emphasized the harm done by some of these policies. But his analysis also reflected a reason why it’s harder to build a consensus to change them: Blaming disparate outcomes on a uniform school discipline policy is a lot less clear than the bald-faced outrages of the civil rights era.

Third, Holder alluded to a shift over time in the nature of the equality agenda. Bigoted outbursts “are not the true markers of the struggle that still must be waged, or the work that still needs to be done,” he argued. “Nor does the greatest threat to equal opportunity any longer reside in overtly discriminatory statutes.” Those statutes and overt prejudices are no longer the greatest threats, and no longer occupy the struggle to be waged, because, as Holder pointed out, they’ve been struck down or “marginalized.” The calls are getting harder because the easy calls have been made.

Fourth, Holder nodded, briefly, to the role of culture in the challenges that remain. Disparate sentences, he noted, “perpetuate cycles of poverty, crime, and incarceration that trap individuals, destroy communities, and decimate minority neighborhoods.” To counter this cycle, Holder commended an initiative called My Brother’s Keeper, which President Obama launched three months ago. In announcing that initiative, Obama spoke bluntly about family and character as well as economics. He talked about “negative behavior” among boys and young men, and about cultivating “a sense of diligence and commitment”:

We can help give every child access to quality preschool and help them start learning from an early age, but we can’t replace the power of a parent who’s reading to that child. We can reform our criminal justice system to ensure that it’s not infected with bias, but nothing keeps a young man out of trouble like a father who takes an active role in his son’s life. … Parents will have to parent—and turn off the television, and help with homework. … Business leaders will need to create more mentorships and apprenticeships to show more young people what careers are out there. … Faith leaders will need to help our young men develop the values and ethical framework that is the foundation for a good and productive life.

These shifts in the equality agenda—from bigotry to structural disadvantage, from obvious wrongs to unintended effects, from legal discrimination to culturally mediated cycles, from the prejudice of action to the prejudice of inaction—don’t excuse indifference or failure. But they do change the character of the problem and how best to address it. Holder is right that we should speak frankly about these complications, not wish them away. They’re a challenge to us all.