On Sept. 27, three days before the government shutdown, President Obama showed up in the White House briefing room with big news. He had just spoken to the president of Iran—the first words between leaders of the two countries since 1979, when Iranian demonstrators seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took dozens of Americans hostage. Obama pledged to resolve U.S. concerns about Iran’s nuclear program through diplomacy. But he took a harder line with his domestic opponents. Discussions about revising the Affordable Care Act “will not happen under the threat of a shutdown,” said the president. As to the debt ceiling, he added: “I will not negotiate over Congress’s responsibility to pay the bills that have already been racked up.”

Republicans erupted at this treatment. “POTUS negotiates with #Iran, Putin but not Congress,” tweeted the chief spokesman for House Speaker John Boehner. The House majority whip, Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., asked why Obama would “talk to the president of Iran, talk to Putin, but won’t sit here and talk to the representatives of the American people.” Fox News host Sean Hannity fumed, “The president will talk to Syria, Iran, Vladimir Putin, but he won’t talk to members of the House.”

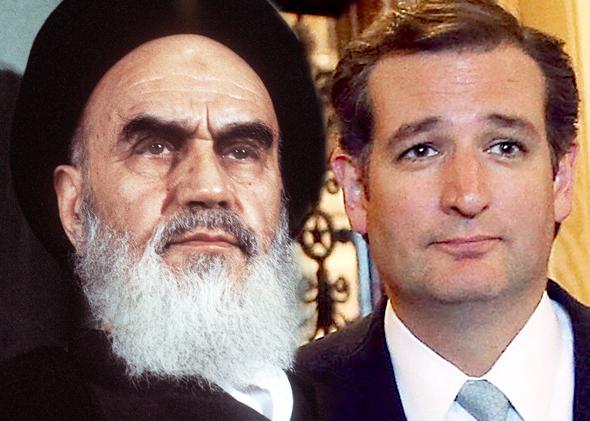

In the week since that ruckus, Republicans have fixed this problem. They’ve decided to behave more like Iran. Not the Iran of 2013, but the Iran of 1979. They’ve taken parts of the government hostage, and now they’re releasing some the hostages, expecting to win praise and concessions.

If you reread the history of the Iran hostage crisis, starting with Congress’ official chronology of it, you’ll see patterns of resemblance. Soon after seizing the U.S. and British embassies, the Iranians adjusted their demands. First they said we had to extradite the deposed shah, who had come to the U.S. for cancer treatment. Then they said we only had to declare him a criminal. Then we only had to authorize an international investigation. But the U.S. held firm. The State Department refused to “negotiate under” the threat. “Only after the hostages are released will we be willing to address Iran’s concerns,” said President Carter.

Iran’s leaders accused the U.S. of intransigence and ignoring their gestures. They claimed that the public was on their side. They blamed the U.S. for raising tensions. To prove their good will, they freed some captives. First the Iranians who had stormed the British Embassy withdrew. Then the regime put out word that on “humanitarian” grounds, it would release U.S. Embassy employees, mostly Asian, who had no “connection with the United States.” A week or so into the standoff, Iran’s leaders came up with another idea: As a public relations gambit, they would release blacks and women.

Members of Iran’s ruling council insisted they had never wanted this confrontation. Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, the acting foreign minister, said that he and others had warned Ayatollah Khomeini that holding the captives would look bad and hurt Iran politically. “I was against taking hostages from the start,” said Bani-Sadr, but “now we are confronted with a fait accompli.” The moderates, trapped by their base, needed President Carter to bail them out. “To free [the hostages] would be a sign of weakness,” Bani-Sadr pleaded. Doing so “without the American government taking a step would be impossible. Our public opinion would not stand it.” The minister claimed that Khomeini had told him, “I can’t move in that direction contrary to public opinion.”

So the Iranians freed the hostages they deemed most useful for PR. “Islam has got a lot of respect for women, and we consider blacks to be oppressed people,” the foreign ministry explained. Tehran radio quoted Khomeini: “Islam has a special respect towards women, and the blacks who have spent ages under American pressure and tyranny and may have come to Iran under pressure.” The regime and the captors tried to turn Americans against their president. At a press conference to announce the release, a sign was posted: “American blacks, our common enemy is President Carter.”

In his order to free the hostages, Khomeini invoked “Islamic mercy.” He gave interviews to several TV networks, portraying himself as more than reasonable. “We have reduced our demands,” he told ABC. Although the Americans were “spies,” he asserted, Iran might release them, in exchange for the shah, as “a kind gesture on our part.” As to the standoff, he told CBS, “It is Carter’s doing. We are against war.” Iran’s news conference announcing the release was staged to blame Carter. One of the hostages was shown on TV saying, “We feel that if this issue was resolved by the president of the United States, the rest of the hostages would be released.”

Today, we’re talking about funding public agencies, not freeing people who are literally held captive. But the tactics are strikingly similar. Republicans began with a big grab—shutting down the whole government—and are now offering to return parts of what they took, bill by bill, in exchange for concessions and the appearance of moderation. “You’re seeing House Republicans over and over again passing reasonable bills to open vital government services, and President Obama and the Democrats refusing to negotiate,” Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, argued Sunday. “It is Republicans in Congress who are passing bills to reopen the parks, to reopen the memorials, to fund cancer research, to fund our veterans.” Sen. John Cornyn, the Republican whip, pointed out that “the House has passed a provision to open up NIH.” Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., pleaded:

We’ve been trying to fund different parts of government all week. We’ve passed bill after bill after bill. … We’ve been passing NIH funding, veterans funding. … We’ve proposed several compromises. Our initial position, and still our position, is we think Obamacare is a bad idea and will hurt the people it was intended to help. But when that didn’t pass, when the Democrats didn’t accept that, we said, “Well, what about a one-year delay?” We’ve been offering compromise after compromise. But you hear from the president and his men and his women, “No negotiation.” His way or the highway.

Thanks for relinquishing some of those hostages, gentlemen. But they weren’t yours to take in the first place. You don’t get to choose which of them go free. Release them, all of them, now.