The fundamental trick in any kind of social manipulation—magic shows, con artistry, business negotiation—is to plant a false premise in the mind of your audience before they’re alert to the risk of deception. By the time the performance begins, the coin is already in your other hand.

That’s what Republicans are doing in the shutdown fight. They’re planting the assumption that the reasonable, moderate, even-handed thing to do is to “negotiate” a “compromise” between the Democratic and Republican positions on the Affordable Care Act. What they’re hiding is the absurdity of the Republican position: that a law passed by both houses of Congress, fully debated in a subsequent presidential election, and unsuccessfully challenged in more than 40 legislative votes by the losing side should be subject to repeal, defunding or delay because a single party, narrowly controlling a single chamber of Congress, otherwise refuses to fund the rest of the government.

Republicans pretend there’s lots of precedent for this sort of “compromise.” They point to 17 previous shutdowns (helpfully outlined by Dylan Matthews in the Washington Post), most of which were resolved by concessions. But when you examine these cases, the claims of resemblance evaporate.

The era of shutdowns ran from 1976 to 1996. In this century, until now, no one has tried to revive that chaos. The shutdowns of that time were about unilateral executive branch decisions, last-minute legislative disputes, or general fiscal restraint, not about overturning policies that had been legislatively enacted. Almost none of them were driven by a single house of Congress defying the other house and the president.

In 10 of the 17 cases, the party that didn’t hold the White House controlled both chambers of Congress. There was a genuine split between the executive and legislative branches. Of the remaining seven cases, one was purely accidental: Congress ran out of time. Two other standoffs pitted both chambers (held by different parties) against the president. In two more, the House, Senate, and president all disagreed with one another. There were only two episodes in which one chamber of Congress stood alone against the other chamber and the president. One took place in November 1983. The other took place in October 1986.

In the 1983 case, most departments were already funded, so there was no danger of shutting down the whole government. One last-minute dispute in this saga was a fight within the GOP over abortion. House Democrats also tried to extract concessions in exchange for increasing the U.S. contribution to the International Monetary Fund—but the IMF increase was new legislation, not something already enacted. Nobody seriously considered risking a shutdown. As soon as pro-choicers realized that the abortion fight might lead to that result, they backed off. The entire fight took place over a three-day weekend, during which government offices were closed, and both chambers passed the necessary spending bill on the Saturday before the Monday on which offices were to reopen. Some shutdown.

The 1986 drama was caused by a logjam of important bills Congress was rushing to finish. The disputes remaining at the end were small, involving labor and construction laws. Again, a major factor in the delay was a nonpartisan filibuster over a side issue—in this case, a project that benefited New York. Congress passed several short-term funding extensions to keep the government open while it hashed out the remaining details. Resolution of these matters was never in doubt, and the only reason the Reagan administration ordered a partial shutdown—which lasted half a day—was to accelerate the process.

The present shutdown threat is nothing like those cases. For the first time, a single party, controlling a single house of Congress—despite having lost the popular vote for that chamber by more than a million ballots in the most recent election—is refusing to fund the government unless the other chamber and the president agree to suspend previously enacted legislation.

That’s some chutzpah. No wonder President Obama and the Senate have refused to capitulate. And for this, in a final stroke of chutzpah, the GOP accuses them of intransigence.

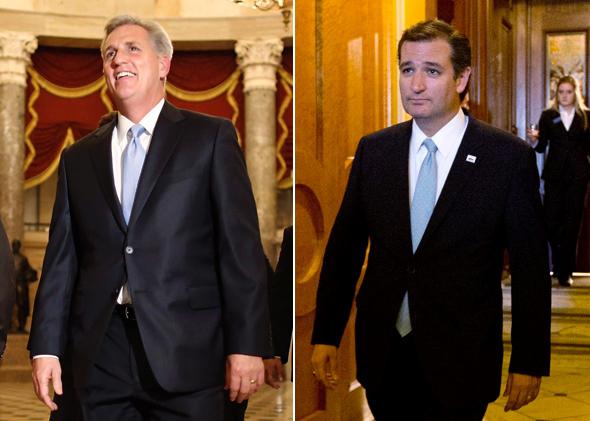

On Sunday, House and Senate Republicans flooded the TV talk shows to bemoan Democratic arrogance. They pointed out that they had scaled back their position from repealing Obamacare to defunding it, and then to merely delaying it. “For all of us who want to see it repealed, simply delaying it … that’s a compromise,” Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, pleaded on Meet the Press. “On the other side, what have the Democrats compromised on? Nothing.” The Democrats “won’t even have a conversation,” Cruz lamented. Rep. Raul Labrador, R-Idaho, protested, “They’re not even willing to meet us halfway.”

“Republicans and Democrats are supposed to find a middle ground,” Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., argued on Face the Nation. “Why don’t we actually bring it to Congress and try to figure out how to meet somewhere in the middle? But [Obama] is saying, ‘100 percent of Obamacare or the highway.’ ” Rep. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., agreed: “Wouldn’t it be great if the president would come and negotiate with us?” Instead, “It is my way or the highway.”

Having demonstrated their reasonableness, the Republicans lambasted Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid as an “absolutist.” Cruz charged that Reid “holds the American people hostage” to liberal demands. On Fox News Sunday, House Republican Whip Kevin McCarthy huffed that Obama will “talk to the president of Iran, talk to Putin, but won’t sit here and talk to the representatives of the American people.”

Sorry, Republicans. Nothing in the Constitution authorizes a single house of Congress to retroactively veto U.S. law by refusing to fund the rest of the government. The manner in which you’re attempting this blackmail—on party-line votes, engineered by the party that lost the popular vote—doesn’t help. The Senate and the president have no legal or moral obligation to humor your demands. Do your job, or we’ll throw you out.