You don’t need a wiretap to hear what people are saying about the National Security Agency’s phone surveillance program. The program’s details, disclosed in a secret court order leaked to the Guardian, show that at least one major company, Verizon, has been legally required to give the government information about its subscribers’ communications. “An astounding assault on the Constitution,” says Rand Paul. “Obscenely outrageous,” says Al Gore. “Beyond Orwellian,” says the ACLU.

Chill. You can quarrel with this program, but it isn’t Orwellian. It’s limited, and it’s controlled by checks and balances.

The program’s purpose, according to administration officials and knowledgeable members of Congress, is to find out who’s been calling or receiving calls from phone numbers linked to known or suspected terrorists. If Tamerlan Tsarnaev had been in contact with somebody flagged as a possible jihadist operative, this is the kind of surveillance that would have brought him to the attention of counterterrorism investigators, even without Russian assistance.

The leaked order is certainly worth discussing. It confirms that previous lines have been crossed. It’s now clear that the surveillance program, which was known to have been conducted under President Bush, has continued under President Obama. Moreover, there’s no requirement that at least one party to the call must be foreign. The order includes calls “wholly within the United States.” Nor is there any requirement that the government show probable cause to justify its demand for any particular record. It only has to offer “reasonable grounds to believe” that the records being sought are “relevant to an authorized investigation.”

But the program is also restrained in several ways. Here’s a list.

1. It isn’t wiretapping. The order authorizes the transfer of “telephony metadata” such as the date and length of each call and which phone numbers were involved. It doesn’t include the content of calls—which is more tightly protected by the Fourth Amendment—or the identity of the callers. The targeted data are mathematical, not verbal. They’re the kind of information you’d request if you were mapping possible extensions of a terrorist or criminal network.

2. It’s judicially supervised. The leaked document is a court order. It was issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance [FISA] Court. To get the Verizon data, the FBI had to ask the court for permission. The Bush administration used to extract this kind of metadata unilaterally. The Obama administration has changed the rules to bring in the court as an overseer.

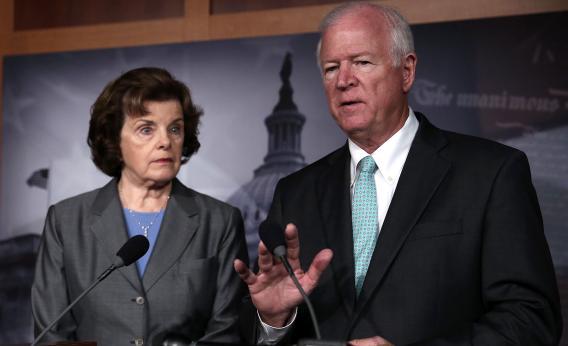

3. It’s congressionally supervised. Any senator who’s expressing shock about the program is a liar or a fool. The Senate Intelligence and Judiciary Committees have been briefed on it many times. Committee members have had access to the relevant FISA court orders and opinions. The intelligence committee has also informed all senators in writing about the program, twice, with invitations to review classified documents about it prior to reauthorization. If they didn’t know about it, they weren’t paying attention.

4. It expires quickly unless it’s reauthorized. The leaked order was issued on April 25 and expires on July 19. That’s the way these orders have worked for years: The court has to review and reapprove the surveillance request, or the authority to transfer the records expires.

5. Wiretaps would require further court orders. The reason the leaked order is so broad is that it applies only to metadata. If, after looking at its map of phone numbers, the government decides that yours might belong to a potential terrorist, it can seek further information, including the content of your calls. But in that case, it has to ask the court for a separate order, which in turn would require enough evidence to override your Fourth Amendment rights.

Is government surveillance worth worrying about? Sure. But even broad surveillance, per se, isn’t outrageous. What’s important is that the surveillance be warranted by real threats, appropriately limited, and supervised by competing branches of government. In this case, those standards have been met.

William Saletan’s latest short takes on the news, via Twitter:

Watch Verizon’s lost “Can you hear me now?” NSA ad: