Every four years, the race for the White House ends in accusations of deceit. Each side says the other spent millions of dollars to lie and skew the outcome. This year’s post-election accounts of backstage calculations and fateful turning points continue that tradition. But if you read these accounts carefully, you’ll find a happy surprise beneath the spin and recriminations: Lies failed. Truth prevailed.

The first two things that went wrong for Romney, according to Jeff Mason of Reuters, were the uproar over his unreleased tax returns and the video of his “47 percent” comments. In Mason’s story, Obama campaign officials gloat over these wounds. But no tactical genius was necessary to inflict them. Romney’s tax stonewalling hurt him because he was hiding information. And the video hurt him because it wasn’t an ad. It was just Romney speaking freely behind closed doors.

Next came Bill Clinton’s speech at the Democratic convention. Numerous accounts, including David Jackson’s in USA Today, credit the former president with the healthy bump Obama got from Charlotte. How did Clinton do it? By delivering a simple, rational, factual appeal. It wasn’t hope and change. It was arithmetic.

Then came the first debate. According to a team report in the New York Times, Obama “showed no interest in watching the Republican debates” during the primary, and he played hooky from his early October debate prep. In his Oct. 3 debate, the Times notes, the president “appeared to be disdainful not only of his opponent but also of the political process itself,” and he “allowed Mr. Romney to explode the characterization of him as a wealthy, job-destroying venture capitalist that the Obama campaign had spent months creating.” In other words, viewers saw the real Romney instead of the caricature they’d been given in Obama’s ads. And they saw Obama taking them for granted, because he was taking them for granted. So Romney gained ground.

Then came Hurricane Sandy. According to Philip Rucker of the Washington Post, Romney’s aides blame Republican Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey for accompanying Obama around the state and praising Obama’s assistance. “A lot of people feel like Christie hurt, that we definitely lost four or five points between the storm and Chris Christie giving Obama a chance to be bigger than life,” a Romney fundraiser tells Rucker. Bigger than life? For millions of people on the East Coast, the hurricane was life. For some, it was death. When Obama left the campaign trail to help manage the hurricane response, he wasn’t acting bipartisan or acting like a president. He was being bipartisan and being president.

While Sandy pounded New Jersey, Romney launched an ad in Ohio claiming that “Obama took GM and Chrysler into bankruptcy and sold Chrysler to Italians who are going to build Jeeps in China.” This, according to the Times, became another turning point:

By every measure, the ad backfired, drawing attacks by leaders of auto companies that employed many of the blue-collar voters that Mr. Romney was trying to reach. The futility of that effort was apparent outside the sprawling Jeep assembly plant in Toledo, which had just had a $500 million renovation for production of a new line of vehicles, a project requiring 1,100 new workers. “Everyone here knows someone who works at Jeep,” [said] Jim Wessel, a supply representative making a sales visit. He said no one would believe the ad.

On the Friday before the election, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the economy had produced an additional 171,000 jobs in October and that employment gains from August and September had been revised upward to 192,000 and 148,000, respectively. That’s more than half a million jobs in three months. In a look back at what went wrong for Romney, James Hohmann and Anna Palmer of Politico write that the jobs report, in the eyes of Republican strategist Fred Malek, was another sign “that in the final weeks all of the breaks were in Obama’s favor.” But if presidential policies influence the economy—which was the entire premise of Romney’s campaign—then three consecutive months of solid job growth coming out of a recession aren’t a lucky break. They’re an accomplishment.

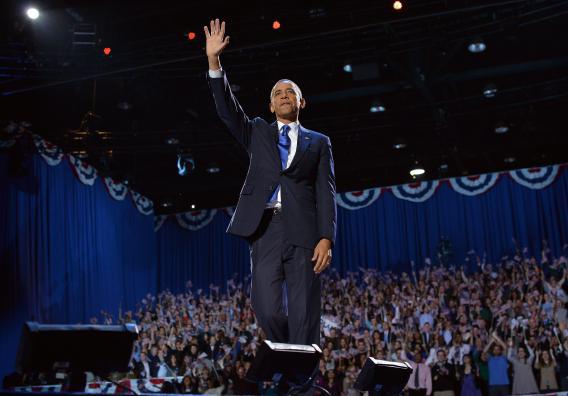

On election night, there was one final reckoning. Obama’s campaign, according to Michael Scherer of Time, was running 66,000 electoral simulations every night on a massive database of polls and voter contact information. That’s how the campaign knew its precise standing in each swing state and allocated resources so that it swept all but North Carolina. Romney, on the other hand, was “shellshocked” by the returns, according to Jan Crawford of CBS News. Crawford says Romney’s strategists “believed the public/media polls were skewed … [T]heir internal polling showed them leading in key states, so they decided to make a play for a broad victory: go to places like Pennsylvania while also playing it safe in the last two weeks.” This rejection of external evidence sealed Romney’s fate.

Even after Fox News called Ohio for Obama—by which time Republican viewers had already had more than an hour to digest the obvious grim trend of the returns—the Romney camp, according to Crawford, refused to concede. “There’s nothing worse than when you think you’re going to win, and you don’t,” a Romney adviser tells Crawford. “It was like a sucker punch.” But when the punch comes from ignored reality, you’re not just the sucker. You’re the one who suckered yourself.

William Saletan’s latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: