Mitt Romney has discovered something shocking about himself: He used to be a governor.

You may have forgotten this. For the past year or so, Romney has been running for president as a businessman. “I spent my life in the private sector,” he has boasted at every opportunity. Politicians aren’t polling well, so Romney didn’t talk about the four years he spent running Massachusetts. He talked about creating jobs when he was CEO of Bain Capital.

Barack Obama answered that pitch with a blistering critique of Romney’s Bain years. Everything Bain did to pursue profits at the expense of labor—outsourcing, offshoring, closing factories, laying off workers—became evidence for the charge that Romney’s business experience was poor preparation for leading a nation. A good CEO, perhaps, but a bad president. In the words of a brutal Obama commercial about jobs being shipped overseas: “Mitt Romney’s not the solution. He’s the problem.”

The attack worked. The latest CBS/New York Times poll asked voters in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania: “Does Mitt Romney have the right kind of business experience to get the economy creating jobs again, or is Romney’s kind of business experience too focused on making profits?” In each state, 48 to 51 percent of likely voters said Romney’s experience was too focused on profits. Only 41 to 42 percent said he had the right kind of experience.

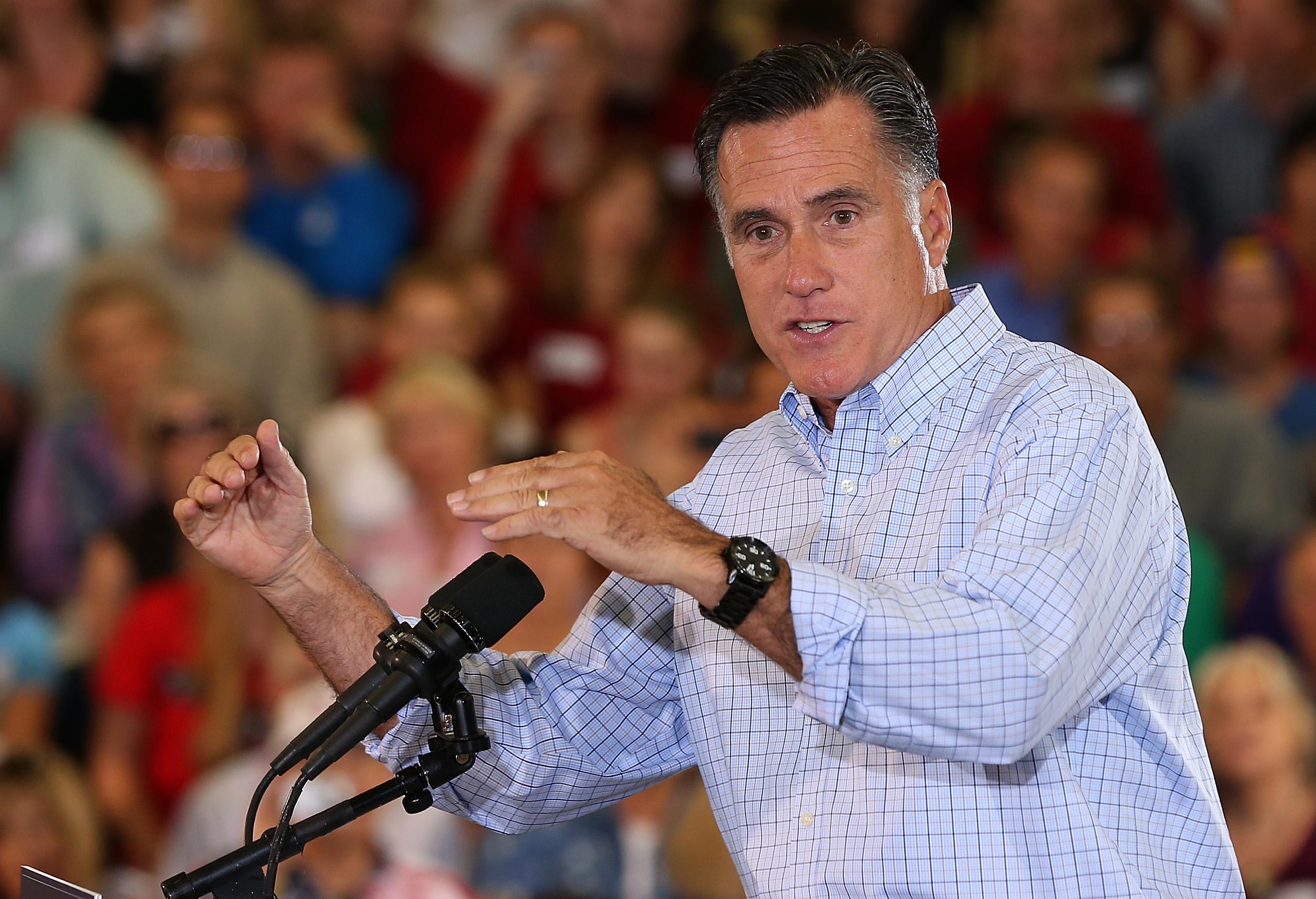

So Romney has retooled. Yesterday, returning from his foreign policy trip, he went to Colorado and blasted Obama’s performance as steward of the nation’s economy. He also outlined a five-point economic plan. Neither of these pitches was new: Romney has been peddling his five-point plan (energy, education, trade, debt reduction, small business) for weeks. What was new was Romney’s self-presentation. He didn’t talk about his life in the private sector. He talked about his tenure as governor of Massachusetts.

In the two months leading up to his trip abroad, Romney gave 25 speeches making the case for his presidency. Only once, in his July 11 address to the NAACP Convention, did he bring up his record as governor, and the only issue he discussed then was education. On three other occasions, he consented to talk about his governorship when questions from the audience prodded him to do so. Other than that, he never mentioned that he had held public office.

That changed on Thursday. Romney arrived in Colorado with a “Presidential Accountability Scorecard” that showed Obama failing to hit his previously set targets on jobs, income, and deficit reduction. Next to the “Obama Record,” the scorecard depicted a perfect rating, on each of these measures, for the “Romney Record [in] Massachusetts.” Five minutes into his speech, Romney began to talk not just about Obama’s failure, but his own success:

Now when I got elected governor … I said to the people that traveled with me, “Would you please write down all the promises I made during the campaign?” … We ended up with 100 promises. And halfway through my term as governor, I actually published all those promises and then checked where they were: which ones I’d succeeded on, which ones I’d tried and couldn’t get done, which ones I was still working on. … And so I have my own record. And you can see it, by the way, on here. … I added jobs. We’ve added more jobs than the president has in the entire country. … I brought the unemployment rate down from 5.6 to 4.7. The home prices: Home prices went up. Budget deficit: I came in, there was almost a $3 million budget gap. I closed it without raising taxes … and finally, family income. That also got better.

Romney’s campaign reinforced this message in a conference call with reporters. “It’s instructive to go back and look at Mitt Romney’s term as governor of Massachusetts,” Romney adviser Eric Fehrnstrom told the press. “He published an accountability scorecard for himself. … He laid out all of the promises, the goals and objectives that he talked about during his campaign for governor in 2002. … We’re asking voters to hold this president accountable for what he said four years ago and what he has actually achieved. And we’re asking to be held accountable to those same measurements.”

As a change of subject, the pivot to Romney’s gubernatorial record makes sense. Running a state, unlike running a private-equity firm, can show the public how Romney functions when his assignment is to help people, not just to make profits. And while the reasons for Romney’s good grades can be debated—it’s a lot easier to post healthy fiscal and employment numbers when you have favorable economic winds at your back—it’s not a bad record to run on.

But the pivot comes at a price. Romney had reasons to run as a businessman. People don’t trust politicians. Having a political record inevitably exposes you to attacks. And Michael Dukakis thought he had a pretty good record, too. If the frying pan of Bain was hot, the fire of Massachusetts could prove to be that much hotter.