When Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto opened gasoline prices to market forces this January, the resulting 20-percent hike—both a step toward the entry of foreign gas stations and a top-up for the treasury’s depleted coffers—prompted weeks of outrage. La Jornada, the country’s leading left-wing daily, reported on the protests one day by splashing its front page with a woman setting fire to Old Glory. The message: The gas hike is the fault of the gringos.

The paper’s take was a deeply oversimplified reading of the situation, but it makes sense in the context of what I call gringophobia, a strain of Mexican nationalism—at times muted, at other times pronounced—that views the United States and its citizens as objects of fear, disdain, and blame for the country’s ills.

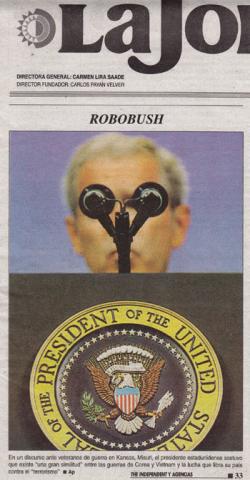

La Jornada

Mexico today is ripe for overt gringophobia, and two singular forces are making it so. One is Donald J. Trump. Since his campaign-igniting “murderers and rapists” speech of 2015, Trump has had no rivals as the American whom Mexicans most love to hate. U.S. media often play up the lighter side of this loathing: old folks bashing yellow-headed piñatas, narcos catapulting bales of marijuana over the border wall Trump has promised to extend. In Mexico, the mirth has fizzled. Between Trump’s nomination and inauguration, the peso lost a fifth of its value. Cowing before the president-elect, Ford canceled a planned plant in Mexico. The economy is anemic, and with Trump’s insistence on tearing up (or at least toning down) NAFTA, prospects look uncertain.

The other force is Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a former mayor of Mexico City and a nationalist-populist stalwart of the left, tagged by the late academic George Grayson as a Mexican messiah. Known to disciples, detractors, and neutrals alike by his initials, AMLO, López Obrador made his first bid for president in 2006 and lost by less than 1 percentage point. Part of his allure owed to his opposition to U.S. influence. The Iraq war had made George W. Bush deeply unpopular to Mexicans, for whom foreign invasions, understandably, are a no-no. On the campaign trail, the then–52-year old AMLO boasted he spoke no English and had never set foot in the USA.

In 2012, his second-place finish was more distant, thanks chiefly to massive support for Peña Nieto from the TV behemoth Televisa, but it did not help that he no longer had an internationally toxic U.S. president to make noises about. In 2018, Mexicans will vote again, and for most of the past year López Obrador has been polling as the front-runner. Political observers tend to agree that the greatest beneficiary of Trump’s election, by far, is AMLO.

* * *

AMLO’s anti-Americanism is not new. Time and again in Mexican history, gringophobia has been utilized for political gain. The trope originated in the 1820s—Mexico’s debut decade as a republic, when U.S. Ambassador Joel Poinsett meddled in politics in favor of local liberals. It mushroomed in the 1840s with the Mexican–American War, known in Mexico as the U.S. Intervention, which ended with the loss of half of Mexico’s territory. The war and the massive land-grab that it engineered angered all elites, but especially the conservatives.

Mid–19th-century ideologue Lucas Alamán argued that unlike Americans: “We [Mexicans] are not a people of merchants and adventurers, scum and refuse of all countries, whose only mission is to usurp the property of the miserable Indians.” Evoking the medieval occupation of Christian Spain by Muslim Africans, the main conservative paper of the time suggested a pan-Hispanic alliance against Americans, the new “Islamites.” A pamphleteer claimed that Protestantism led to “sedition, disorder, cruelty, blood, and death.”

Conservatives lost the upper hand in the 1860s, thanks to a fateful alliance with a French-imposed emperor, and the ensuing Age of Liberalism witnessed a U.S.–led building of railroads and revival of mines. The rich whined about an invading “swarm of ants” that brandished revolvers and frequented barrooms, and they satirized the rudeness of the Yankee workers with whom they sometimes had to share train compartments. But outside the contact zones of mining camps and oil fields, resentment was limited to rarified circles.

All that changed after 1910, when Mexico was plunged into a decadelong revolution that produced what was arguably the world’s first socialist constitution. It was now the left, much more than the right, that waved the banner of national sovereignty. And gringophobia evolved too, entering popular culture on a massive scale.

Folk ballads known as corridos began to mock Americans for their lack of manliness, their greed and cruelty, and their contempt for Mexican workers. One balladeer opined: “The gringo is very despicable, and our eternal enemy.” Another claimed Americans wished to exploit all things Mexican, from oil and silver to “the country’s beautiful women.” Yet another observed that unemployed oilers in Tampico were so angry, “they only want to eat gringos, raw and also roasted.”

Political cartoonists drew American investors with large girths, sneering smiles, and outsized diamond rings. A literary excoriation of Yankee business activity proliferated, as it did throughout Latin America; unlike ordinary Americans, whom novelists often absolved, investors were stereotyped as cold, racist, immoral, sometimes lustful. A nascent film industry started to depict the exploitative U.S. businessman as a stock character.

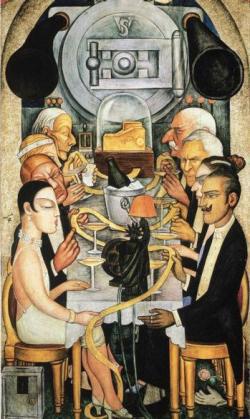

While much of this was spontaneous, some of the new sentiment was fostered by the state. School textbooks fingered U.S. greed as a cause of the Mexican–American War. Diego Rivera, the muralist, was invited to paint at the Education Ministry, and his frescoes included a group portrait of John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan Jr., and Henry Ford. Rivera made them into wizened fiends, dining on stock-market ticker tape, in what an American diplomat called a display of “virulent and blatant hatred of the United States.”

Diego Rivera

Mexico’s new rulers needed a useful bugaboo, for their biggest concern in the 1920s and ’30s was holding the state together. The 10-year revolution was followed by a series of lesser rebellions that threatened to topple the government. Perennially short of cash, the state had limited options, but one thing it could easily do—to satisfy the constitution’s radical promises and to strengthen its tenuous hold—was to seize U.S. assets.

Per one estimate, foreigners—mostly Americans—had come to own 27 percent of Mexico’s surface area by 1910. Expropriations became the order of the day, the land typically redistributed among the peasant and rancher majority. And the policy reached a populist climax in 1938, with the seizure of the U.S.– and U.K.–owned oil companies. The president who made that jackpot-hitting call, Lázaro Cárdenas, remains the most popular figure in 20th-century Mexican history.

* * *

Cárdenas could pull off the oil seizure in great part thanks to Washington. Under Franklin Roosevelt, the United States had nurtured a Latin American Good Neighbor policy, following decades as the backyard bully (grabbing Puerto Rico from Spain; invading Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution; occupying Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic for years on end). And so Mexico entered World War II on the side of the Allies, despite popular misgivings, even incomprehension. In some small towns, radio listeners greeted the declaration of war with: “Viva México! Death to the Gringos!”

Afterward, good neighborly harmony came to be relegated in favor of Cold War anti-communism. Modern Mexico’s first civilian president, Miguel Alemán, was happy to sing the new tune. A conservative, he led the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in a firmly pro-business, pro–U.S. direction that, despite some populist flourishes, has remained the party’s M.O. to this day. (Peña Nieto’s feeble attempt to appease Trump last August, by inviting him to Mexico during his campaign, belongs within this rhetorically uneven but practically deferential tradition.)

The PRI, which ruled uninterrupted from 1929 until 2000, was a very broad church. Its left wing grew ever unhappier with the turn their “revolution” was taking. Matters came to a head in 1959, when Fidel Castro’s rebels rode into Havana and started imposing a state-directed economy. Leftists hailed the Cuban model as a reminder of abandoned ideals. Growing U.S. hostility to Castro only bolstered their case.

Seeking to fix their ire on a symbol of all that had gone wrong, in order to sway both the PRI and the public toward a re-embrace of socialism, many writers and politicians opted for one William O. Jenkins. A native of Tennessee, Jenkins had moved to Mexico in 1901 and made successive fortunes in textiles, property trading, sugar, banking, and the film industry. He had done so through a complex mix of entrepreneurial savvy and befriending the powerful, chiefly among the right wing of the PRI. In 1960, Time would call him the richest man in Mexico.

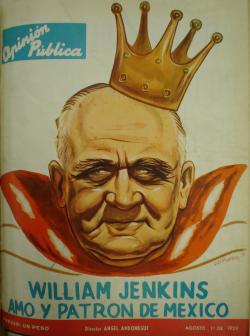

Between 1959 and 1961, with debates over Cuba at a peak, Jenkins was subject to a barrage. One magazine claimed Jenkins ruled over his adoptive state of Puebla, murdering opponents and imposing governors and mayors. As owner of Mexico’s No. 2 bank, he exploited thousands of employees, and the fact that 70 percent were female made him “a great national pimp.” Why was “the most pernicious foreigner that we have” allowed to remain in Mexico? Surely because he had bribed several presidents. The cover caricatured him as a despot, while its title blared: “William Jenkins, Lord and Master of Mexico.”

La Jornada Baja California

The most influential left-wing organ of the day, Política, was more specifically gringophobic. A 1960 photo essay about a sugar plantation the American had once owned, “A Hell on Mexican Soil,” claimed the estate was still controlled by Jenkins, of whom it said: “The greatest devil is blond.” (Mexican caricatures of U.S. businessmen always made them fair-haired.) Other media took to calling Jenkins a “the pernicious Yankee.”

While some of the attacks against Jenkins were accurate, others were exaggerated, still others fabricated. Even the truths were often distortions of a sort, as they tended to ignore how Jenkins’ busting of unions, arming of vigilantes, evading of taxes, monopolistic bullying of rivals, and backing of autocratic politicians was standard practice among Mexico’s business elite. Jenkins had become one of them, for he never returned to the United States and did not repatriate profits, but he took more flak because he was a gringo.

The battle for the soul of the PRI was won by the right. Continuity triumphed when the president, following ruling-party practice, hand-picked a conservative authoritarian as his successor. But Jenkins’ vilification mattered: It contributed to an ever-more-shrill rhetorical struggle, echoed in the streets with student marches; chants of “Cuba sí, Yanquis no!”; and occasional killings. The battle polarized Mexico for years and inexorably arrived at a bloody outcome in October 1968. Ten days before the Mexico City Olympics, the army halted a growing protest movement by killing dozens, perhaps hundreds, of students.

* * *

For more than two decades now, Mexico and the United States have drawn generally closer. NAFTA played a huge part, though not entirely as its neoliberal architects intended. Its mid-1990s opening of Mexico to subsidized U.S. maize prompted several million peasants and their families, no longer able to sell the surplus from their cornfields, to migrate north. In turn, years of back-and-forth movement by these migrants have tempered old prejudices about Uncle Sam. Millions of Mexicans have now seen him for themselves.

But two key factors keep gringophobia in play. First, believing the worst of the United States remains an article of faith within some sectors of society, such as many faculty in the social sciences at the big public universities, along with media such as La Jornada and the popular, combative newsweekly Proceso. In August 2014, when Peña Nieto’s investment-enticing energy reform became law, the front-cover verdict of Proceso was simple: “The Hand Over”—that is (so its lead article made clear), of Mexico’s oil to the gringos.

Second, national opinion remains subject to huge mood swings. In 2003, following Bush’s invasion of Iraq, pollsters Latinobarómetro found that just 41 percent of Mexicans had a positive view of the United States, while 58 percent held a negative view. Thirteen years later, during Obama’s final year, only 15 percent expressed a negative view, while 76 percent had a positive one. Such polls suggest that a major determinant of Mexican opinion is the occupant of the White House. Moreover, not counting don’t-knows, Latinobarómetro last year found that just 12 percent of Mexicans held a negative opinion of Obama; 94 percent disliked Trump.

With Trump in the Oval Office, Mexico may never have been as fertile a field for politicized gringophobia as it is today. The land conquered by Gen. Winfield Scott in 1847 was less a nation than a map of ill-connected states, much of its populace likely oblivious of the invasion until well after it had happened. When the U.S. Marines took Veracruz in 1914, news still reached only a minority, for 85 percent of Mexicans remained illiterate.

AP/La Jornada

Only the 1960s offer a proximate parallel. But Mexico had no electoral democracy then. Today, three parties jostle for supremacy: Peña Nieto’s ruling PRI; the conservative PAN, which governed from 2000 to 2012; and AMLO’s upstart Morena, an acronym for Movement for National Regeneration that just happens to echo the Spanish word for “dark-skinned person.”

So far this year, López Obrador has been somewhat muted in his nationalism. In February, he even visited the United States, holding rallies for migrant workers. While blasting Trump for his anti-migrant, wall-building postures, he took care not to criticize the United States overall. California is “a refuge and blessing for immigrants,” he told a Los Angeles crowd. “Long live California!”

His frequently firebrand oratory, which sometimes recalls Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, is a great part of the attraction to many AMLO devotees. He likes to refer to the PRI and the PAN as the “mafia of power.” Policy-wise, however, López Obrador currently seems keener to follow the more moderate path of Latin America’s other leading leftist of the new century, former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva. In February AMLO enlisted several prominent businessmen to his circle of advisers.

Yet as the July 2018 election draws closer, tightness or slippage in the polls may prompt López Obrador to revive some of the us-and-them rhetoric toward the United States he used in 2006. Past poll swings suggest there are votes in such language—perhaps not enough to lock an absolute majority, but enough to finesse the difference in a three-way race.

And what then? Would a President AMLO succumb to the temptation—à la Venezuela’s Chávez and Nicolás Maduro—of blaming the United States whenever times are tough? Or would he rather, like Lula and his successor Dilma Rousseff, denounce opposition politicians at home? As long as Trump is in the White House, the easier option could well be the former.