The French presidential election on Sunday is expected to be a cakewalk for Emmanuel Macron, the center-left technocrat and financier running against the anti-immigrant nationalist Marine Le Pen. If some suspense remains despite polls consistently showing Macron taking 60 percent of the vote, it’s for two reasons. The first is that Le Pen’s extreme positions, like her desire to quit the European Union, have rattled the French and their neighbors. Ratings agencies say converting French debt from euros to francs, for example, would constitute the largest sovereign debt default in history.

The second is that this is a race unlike any the Fifth Republic has ever seen. It’s the first modern French presidential race missing a candidate from one of the two biggest parties, the Socialists and the Republicans. It’s also the latest election to upset the familiar notion of national politics operating on a spectrum from left to right and the familiar schisms that accompanied the old model. What has emerged is a divide that’s nearly urban-rural, but with exceptions that defy that simplistic characterization. A new political geography is in place in France, and the French are finding a new way to talk about it, in a struggle over language, history, and politics that mirrors the one underway elsewhere in Europe and in the U.S.

The hot term in Paris right now is la France périphérique, or “peripheral France,” a term popularized in an eponymous 2014 essay by the geographer Christophe Guilluy. Peripheral France describes the fractal swath of French territory isolated from the productive centers of the global economy. Think of an isochrone map, where bands of color denote travel time from a central location, adapted to correspond to France’s thriving cities: Paris, Lyon, Bordeaux, and a handful of others. Those places make up France métropolitaine; the rest, even some city centers, is peripheral. Peripheral France is often invoked in conversations about the success of the National Front, and Guilluy has embraced his role as prophet of the electorate. “Macron is the candidate of the globalized metropolises,” he said in an interview with Le Monde last weekend.

It’s a similar pattern to the one that emerged in the United States on Nov. 8 after Hillary Clinton engineered a near-sweep of the nation’s most populous counties but ceded smaller cities and traditionally Democratic countryside to her anti-immigrant, anti-trade, and anti-urban rival. In France, Le Figaro somewhat reductively calls the election “the candidate of cities against the candidate of fields.” The phenomenon is impossible to ignore and nearly as difficult to talk about.

That’s partially because there are important exceptions to the urban-rural breakdown: Though plenty rural, western France is staunchly anti–National Front (perhaps a result of lingering Catholic influence), while northern and eastern industrial cities like Calais are lepéniste. Regions of rural America like New England, Minnesota’s Iron Range, the Black Belt, and the Latino Southwest rejected Trump; urban areas like Erie, Pennsylvania, and the Detroit suburbs embraced him. It’s not accurate to describe these reactionary, xenophobic movements that have grown across the West merely as rural, even if their sense of race-based nationalism is rooted in pastoral nostalgia.

So what do we call this place, and its ascendant coalition of voters against the status quo? Here, “rural America” isn’t right. “Middle America” is vague. “White America” doesn’t tell the whole story. “Non-metropolitan America” is accurate but unwieldy. “Flyover country” is pejorative, while the “Heartland” and “Real America” reinforce a pernicious stereotype of the American city (and its diverse population) as an aberration. The equivalent part of France has also been called, with the same implication, La France profonde, a region of deeper and more authentic Frenchness.

The same dilemma exists in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Poland, and Hungary, where new right-wing coalitions have surged or triumphed at the ballot box. Traditional political boundaries are becoming obsolete, but an urban-rural framework doesn’t quite apply. In France, support for Le Pen in cities—and there’s quite a bit of it in provincial centers—correlates with commercial vacancy rates. In the U.K., the Brexit bloc includes cities like Sunderland and has been referred to simply as the “left behind,” a term that applies just as well to places as to people.

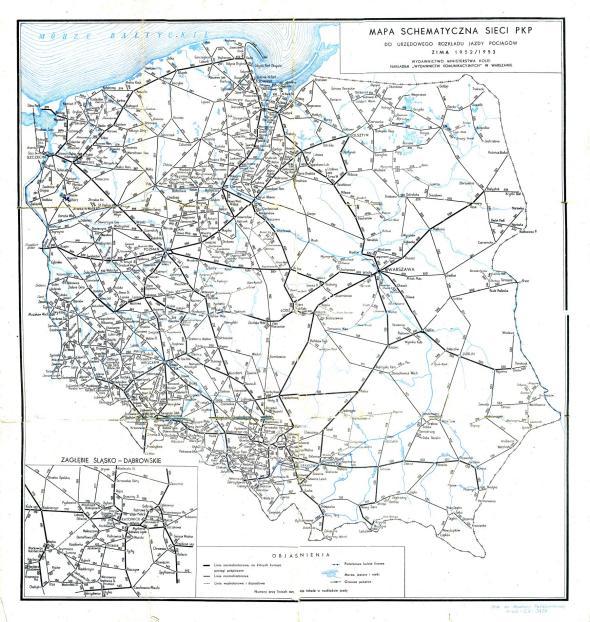

In Poland, the Catholic nationalist Law and Justice party took power in 2015. “The party appealed to those who felt left out of the new, cosmopolitan Poland,” wrote James Traub in the New York Times Magazine in November, “with its cafe culture and its easy flights to London and Frankfurt.” Their political base is in southern and eastern Poland, in an area whose long-standing poverty and lack of development has earned it the nickname “Polska B.” The more prosperous regions closer to the German border make up “Polska A.” In Hungary, and the Czech and Slovak republics, the most pronounced contrast is between a EU-looking West and an inward-looking East. These divides are all centuries old but have become much more pronounced since the fall of the Iron Curtain. Now they correspond to internal political affiliations.

The naming goes both ways, of course. The list of stereotypes for cities and the people who vote in them is too long to recount here, but where there’s a reactionary, anti-globalism party, there’s a way of talking angrily, with racial or religious undertones, about the city, alternately elite and decrepit.

In the southern Netherlands, a former Spanish-controlled region where lapsed Catholics are jumping to populist parties on the left and right, people still talk about the “arrogant and cold-blooded Hollanders” from the West, says the Dutch geographer Josse de Voogd.

In Hungary, the late far-right politician István Csurka used the expression bűnös város, or Sin City, to talk about Budapest, the liberal, Western European–looking capital where about one in three Hungarians (and Central Eastern Europe’s largest Jewish population) lives. When the left wins in and around Budapest, says Péter Krekó, an expert on the Hungarian far-right, the expression comes up again and again. It hearkens back to much older anti-urban, anti-Semitic tropes in Europe—see also “rootless cosmopolitan,” the Stalinist slur for Jewish intellectuals—and, he notes, was used much earlier by the Hungarian leader and Hitler ally Miklós Horthy.

In France, Le Pen has said she is a candidate for all, but has a familiar way of framing the election as a battle between globalism and patriotism. “A runoff between a caricature of an unabashed globalist like him and a patriot like me, that would be ideal,” she said of Macron in January. Her language doesn’t portend a new politics of globalism versus nationalism in the West, however. It’s catching up to a culture that proudly looks inward and backward.

But names give something back, too, legitimizing or diminishing the coalitions they describe. La France peripherique marginalizes the people it describes, by definition. For people who consider themselves the guardians of French heritage, it implies an outsider status they’re unlikely to embrace.

Still, in some ways, Le Pen has it easy. It’s natural for anti–status quo candidates like her and Trump to delineate the divides—to speak loudly about the globalists, the immigrants, the elites, the bunos varos, and the Polska A of the world. What’s harder is for the defenders of a pluralistic open society to find an effective, compassionate, and accurate way of referring to what remains.