More than 40 years ago, Mao Zedong reportedly said, “All is chaos under heaven, and the situation is good.” It’s as good a description as any of Donald Trump’s governing strategy. In the 10 days he’s served as president, Trump has demonstrated, through his attacks on the media, his disregard for international and constitutional norms, and his pathological obsession with his own reality, that like the Communist revolutionaries of yesteryear, he is more interested in transforming America than running it. It’s a “shock to the system,” as spokeswoman Kellyanne Conway tweeted on Saturday. “And he’s just getting started.” Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that Trump adviser Steve Bannon once proudly described himself as a Leninist. “Lenin,” Bannon told the former Marxist intellectual Ronald Radosh in 2013, “wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.”

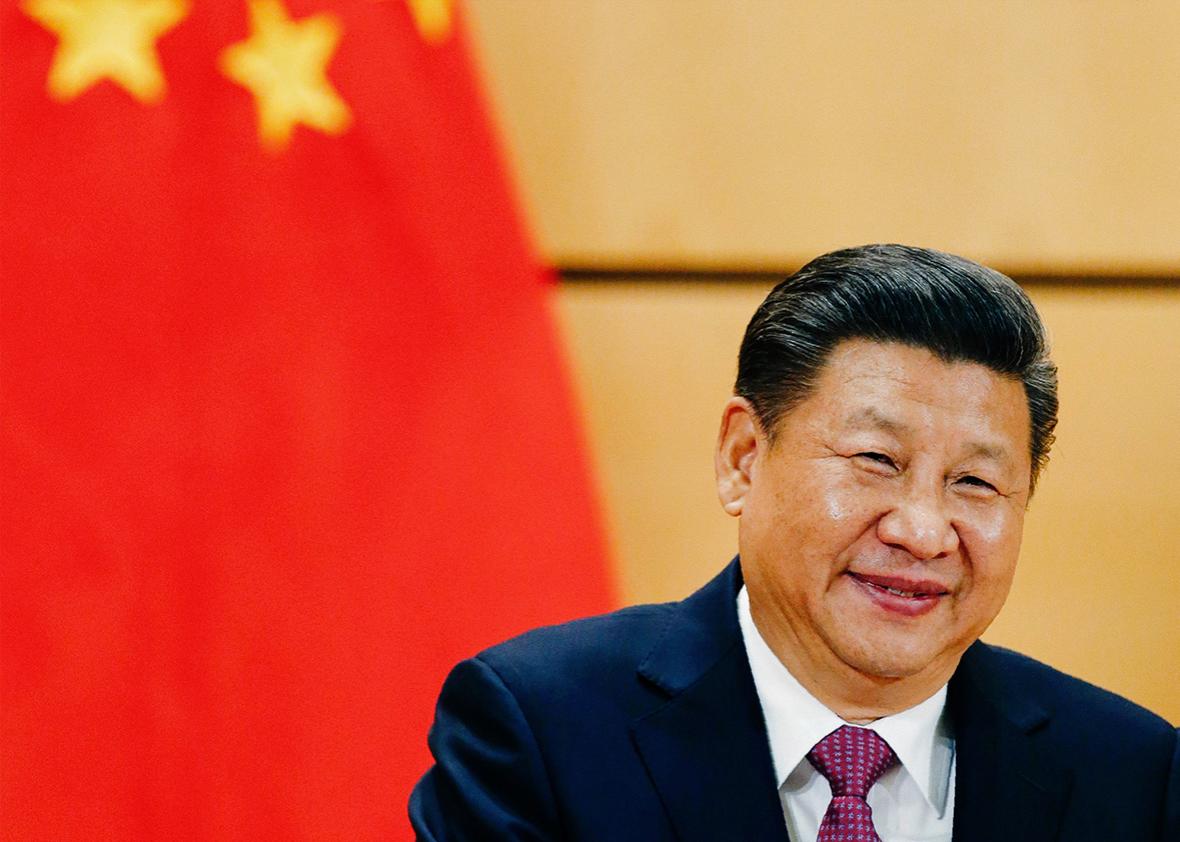

All this puts the People’s Republic of China in a strange position. Though the modern Chinese state may have been founded on revolutionary chaos, after Mao’s death in 1976, China moved away from a chaotic authoritarianism and toward one predicated on order, internationalism, and fealty to the state. In the years since taking office in November 2012, China’s Communist Party Secretary Xi Jinping has shown that he wants to preserve the system that brought him to power. “China took a brave step to embrace the global market,” Xi said in a well-regarded speech at Davos earlier in January—the first time a Chinese president attended the international elite gathering. “It has proved to be the right strategic choice,” he added. All the very recent debates over how China’s rise would disrupt the international system now seem positively quaint. In the age of Trump, it’s America that’s disrupting international norms while China positions itself as the defender of the status quo. This strange entwining of history—Trump adopting anarchic anti-establishment policies formerly associated with Communist leaders, while Xi burnishes his global liberal credentials—will benefit China’s international interests at the expense of the United States.

In the months since Trump’s election victory, there’s been a widespread assumption that Russia would be the big global winner in the Trump era. After all, the U.S. intelligence community has accused Russia of meddling on Trump’s behalf in the election, and the candidate has spoken openly about his skepticism of NATO, his desire to partner with Russia to fight ISIS, and his fondness for Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile, Trump bashed China consistently on the campaign trail, saying, “What China is doing is beyond belief” and that its unfair trade policies “rape” the United States. Even before taking office, he enraged Beijing with his provocative December phone call with the president of Taiwan. Trump has also surrounded himself with outspoken China hawks. The director of his newly created National Trade Council, Peter Navarro, has long argued that China’s handling of its currency, the yuan, “is threatening to tear asunder the entire global economic fabric and free trade framework.” Trump’s nominee for the United States trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, has called for a “much more aggressive approach in dealing with China.”

But the events of Trump’s presidency so far, and many of the policies he’s laid out, serve to strengthen China and its place in the world. The new U.S. administration is—seemingly inadvertently—giving Beijing wide latitude to create policy in Asia and strengthening the global appeal of China’s political system.

The biggest win for China so far was Trump’s decision to cancel the planned Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, gifting China a far freer hand to dictate trade policy in its backyard. The TPP—a proposed 12-nation trade pact representing roughly 40 percent of the world’s economic output—would have lowered tariffs, simplified international regulations, and cut red tape for cross-border trade and investment for American companies and companies from member states. Beijing understandably hated the TPP: Not only did the agreement pointedly exclude China and reportedly emphasized environmental regulations and intellectual property, but it competed with two Chinese-led trade strategies—One Belt, One Road, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. The former is a grand global strategy meant to link China with the rest of Eurasia, while the latter is a 16-nation trading bloc that pointedly excludes the United States. China benefits from the RCEP in much the same way that the United States would have benefited from the TPP: lowering the price of goods for Chinese consumers and expanding the market reach for Chinese companies.

But China’s benefits from the failure of the TPP go beyond economics. By increasing the chances that its two trade strategies dominate in the region, Beijing can have far more say in drafting policies that benefit its people, its government, and the party. The more that Chinese-led initiatives become the norm for the way countries around the world conduct trade, the less they will feel able to host the Dalai Lama, criticize China’s human rights abuses, or facilitate Taiwan’s linkages to the global economy. “When more than 95 percent of our potential customers live outside our borders, we can’t let countries like China write the rules of the global economy,” Barack Obama said in an October 2015 statement on the TPP. And yet, here we are.

Another example is Trump’s stance on climate change, including his never repudiated 2012 tweet calling it a hoax created by Chinese companies. Instead of offering a convincing or compelling alternative to measures such as the Paris Climate Agreement and agreements to cut emissions, Trump’s stance is purely destructive. Beijing, which despite its heavy pollution can at least claim that its leaders accept established science and view climate change as a problem, gets to look like the responsible adult in the room.

There is even a silver lining for Beijing to Trump’s comment that the “one China” policy, under which Taiwan is recognized as a part of China rather than a separate country, is now negotiable. Again, Trump is discarding a policy without offering one in return. If Beijing so chooses, it can change the way it treats Taiwan—perhaps by more directly referring to it as a Chinese province in bilateral discussions, for example, or acting more aggressively the next time United States announces arms sales to the island. Without a new U.S. policy to replace the old one, everything is up for grabs. A change in the status quo is more likely to benefit Beijing, which has more leverage and more experience negotiating on Taiwan issues.

And sometimes China’s benefits arise out of the uncertainty created by constant policy reversal. Consider U.S. ally South Korea, which hosts approximately 28,500 U.S. troops. In March, Trump said, “We are better off frankly if South Korea is going to start protecting itself,” alarming a country that has long depended on U.S. defense—especially from its belligerent neighbor North Korea. Even more worryingly to many in the country, he has said several times said that South Korea (and Japan) “would be better off” if they acquired nuclear weapons. In his inauguration speech, Trump issued “a new decree to be heard in every city, in every foreign capital, and in every hall of power … from this moment on, it’s going to be America First.” Yes, the Secretary of Defense James Mattis will make his first foreign trip to South Korea, but as John Delury, a professor at Yonsei University in Seoul, has said, “Allies seek reassurance but all Donald Trump has given them so far is doubts.”

How does China benefit from this uncertainty? By exploiting American inaction to push South Korea to change its behavior. Beijing does not approve of South Korea’s planned hosting of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense platform, a missile shield that could shoot down North Korean missiles but could also help defend American or Japanese military targets from a Chinese attack. So in the months since Trump won the election, Beijing has upped its pressure on South Korea to cancel THAAD—most recently by punishing the South Korean conglomerate Lotte that owns the land where THAAD would be built. It’s reasonable to assume that if Trump had given clearer signals about U.S. commitment to South Korea, Beijing would have acted more cautiously.

The soft power aspect is more diffuse but no less important. Each time Trump does something such as signing an order restricting Muslims from entering the United States, it diminishes the attractiveness of the American political system. Each time Trump lies, or criticizes a media outlet for speaking out against him, or obsesses over his popularity in pathological ways, it makes the Chinese system look more appealing by contrast. (Trump’s refusal to criticize Beijing’s human rights abuses helps as well.) This benefits Beijing not only internationally but, more importantly, domestically. America, the only successful large country in the eyes of many Chinese—Russia, India, and Indonesia don’t count—has (or had) a thriving democratic system, which some Chinese activists and liberals believe would work in China. Each time Trump belies that notion, it weakens the hope of those who want to see Chinese people choose their leaders.

That’s not to say Trump trampling on the international order is the ideal global situation for Beijing or even that the Chinese ruling elite preferred a Trump presidency over a Hillary Clinton one. Beijing’s biggest risk is miscalculating how Trump will respond because of the uncertainty caused by the seemingly intentional ambiguity of some of Trump’s policies and the untested, unexplained, and unprecedented aspect of Trump and some members of his team—exacerbated by the infighting of a new and inexperienced team of policymakers. Moreover, it’s incredibly early in Trump’s presidency: He could start implementing policies that hurt China’s interests. Currently, Beijing is successfully exploiting an uncertain situation.

Even a trade war could work out to China’s advantage. Putting huge tariffs on Chinese exports could nudge Beijing to make smarter domestic economic decisions: Currently, many Chinese liberal economists (and some liberal policymakers as well) believe their country should shift its economy to one more reliant on domestic consumption than on exports and manufacturing. By offering an external reason to do so—a Trump trade war—this could give ammunition to liberal economic reformers to make the hard decisions that would benefit China in the medium and long term.

During the Obama administration, there was a quiet debate among Asia strategists over whether a strong, authoritarian China or a weak, chaotic, and potentially democratic China better serves America’s interests. Funnily enough there seems to be a third reality emerging—one unthinkable even months ago: a China that is strong; confident; and, in the eyes of the world outside its borders, surprisingly liberal. No matter how much Trump praises Putin, it’s hard to image the president improving Moscow’s fortunes as much as he has Beijing’s.