BERLIN—I chose sleep over Brexit. When I shut down my laptop on Thursday night, a British friend had just posted on Facebook: “Polls closed. Start of all night prayer vigil in front of TV …” I would have none of it and went to bed. In 20 years of reporting from Europe, I had never stayed up for a Super Bowl or U.S. presidential election—and I wasn’t about to begin making exceptions for British plebiscites.

The crying of a neighbor’s baby—perhaps a young “Remainer”—woke me early Friday morning. I switched on the BBC to hear the presenter make an unusual confession: “We don’t know what we’re talking about.”

On Twitter, mayhem was breaking out. Gold up, pound down. I retweeted people I’d never seen before in my feed: author J.K. Rowling (“Goodbye, UK”); BBC veteran reporter John Simpson (“biggest world change since USSR fall”); and Marion Le Pen, third-generation heiress to France’s right-wing Front National (“VICTORY!”).

A colleague from Poland advised his British-born wife to get a Polish passport. It was high time to make some coffee.

Social media provided real-time insight into how my friends were experiencing Brexit across Europe. A Russian wrote on Facebook: “British friends—Now you know why Putin wins and would be winning even at a free and fair election.” Posting a photo of a Berlin store selling East German and European Union flags, a German commented: “summer sale on surplus items.”

Not everyone saw the irony in England’s retrenchment and the possibility of the United Kingdom and the European Union getting wrecked in the process. Friends from Eastern Europe, especially, struggled to make sense of Britons’ cavalier rejection of the greatest economic union in history.

Czechs and Estonians who found freedom after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall know to value their independence. Yet they voluntarily gave up part of their sovereignty to join the European Union. To reduce their motivation to mere economic gain would be to cheapen their herculean achievement. People across the region demanded democracy, rule of law, and a reconnection to the European mainstream.

Brexit, on the other hand, was largely driven by a fear of immigrants—not of dark-skinned boat people but of pale Poles and Lithuanians taking advantage of the European Union’s freedom of movement to settle in Britain. The “Leave” campaign was not racist as much as it was tribalist, a stark reminder that the wars fought on European soil were largely orgies of white-on-white violence.

War broke out in the Balkans 25 years ago when first Slovenia, then Croatia, seceded from Yugoslavia. Serbs living in Croatia rejected independence, setting off a bloody spiral of violence that would engulf the region. In the Brexit referendum, Scotland and Northern Island split with England and Wales, voicing their preference to stay in Europe and raising the specter of more disintegration.

“They were calling us tribal and primitive when rightwing fools chose to tear my country apart. Because it was what the majority wanted,” wrote a Serbian friend who had emigrated to Germany after the war. “I know exactly how it feels—I’ve been there. And I know how it’s going to end if you just keep shaking your head in disbelief instead of taking action.”

In Ukraine, where people lost their lives in protests for closer alignment with the European Union, there was a similar sense of bewilderment. Only pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk, a host city in the European soccer championships four years ago, applauded Brexit, comparing it to their fake referendum in 2014.

“Britain simply freed up a place for us,” a Ukrainian friend said hopefully on Facebook, suggesting that Ukraine could take Britain’s vacant EU spot. But a British colleague who had covered the escalating conflict with me was less optimistic. “The last time I felt like this was in Donetsk, April 2014,” he wrote.

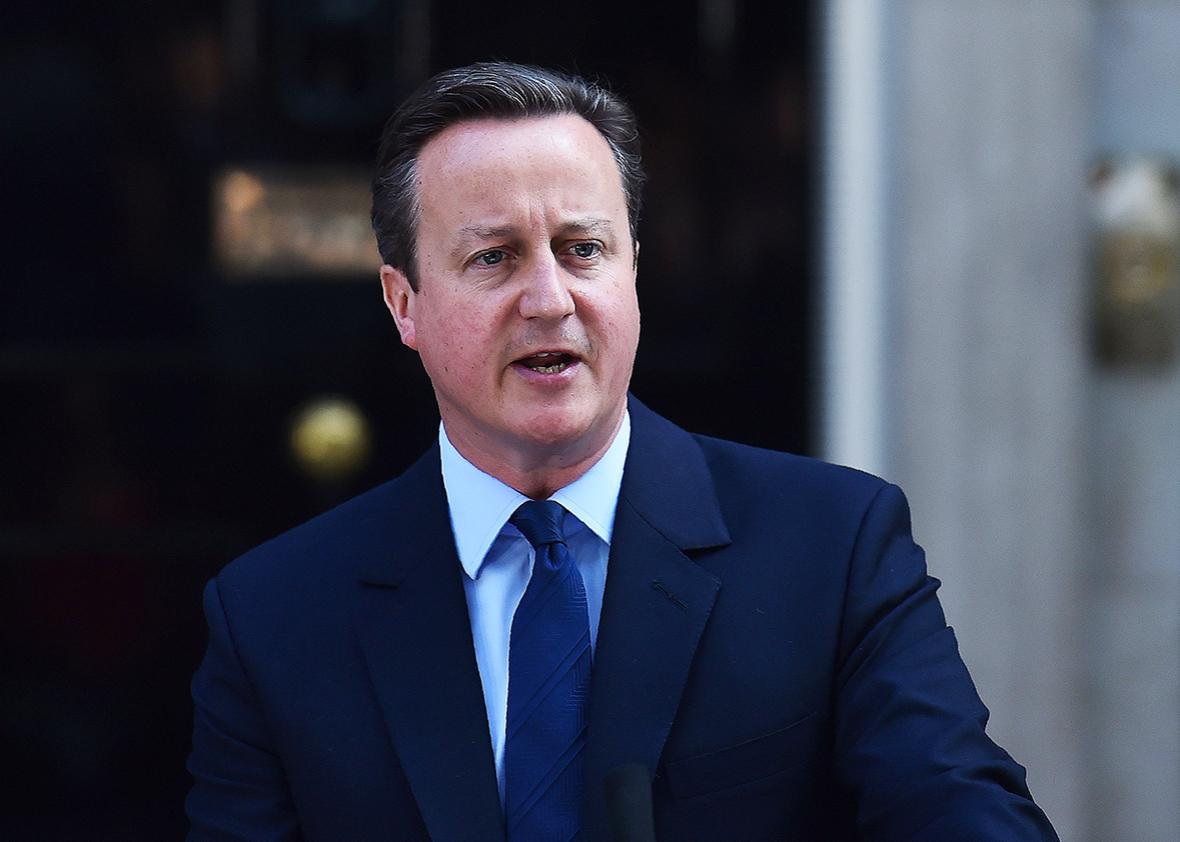

It’s probably human nature to take for granted what you have until it’s too late. British Prime Minister David Cameron bears the greatest responsibility for calling the referendum—and then blowing the “Remain” campaign. “Thank you Dave, and everyone who voted for him,” a British colleague vented on Facebook. “Now go away. Presumably to your holiday home somewhere in the EU.”

Europe’s biggest problem is that it doesn’t have the leaders who can lay down a convincing case for the European Union and where it’s going. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande, both masters of the status quo, lack the vision to rally their own countries, not to mention the rest of Europe. Peter Altmaier, Merkel’s chief of staff, fell painfully short when he tweeted:

European patriots went to bed with a sense impending doom. They knew their world had changed inalterably, but they couldn’t yet tell how. Fortunately, British humor was still intact.

“Oh do cheer up, dear,” one British colleague consoled a despondent Facebook friend. “This time 100 years ago we were getting ready to launch the Somme offensive.”