This week, you have a good excuse to pry your eyes off the morbid carnival that is the U.S. presidential election, because for the next few days the most fascinating political story in the world will be unfolding in Great Britain. On Thursday, U.K. voters are set to cast their ballots in a referendum on whether to leave the European Union. If the so-called “Brexit” camp wins out—Britain+exit=Brexit, like Grexit—it would be an unprecedented and potentially seismic event in EU history.

In many ways, the leave campaign is being driven by the same resentments toward immigrants and globalization that have powered right-wing movements across the Western world, including the political ascendance of a certain glorified Twitter troll here in the United States. And if those parallels to U.S. politics weren’t enough, one of the main protagonists in this drama—Boris Johnson, unofficial mascot for the leave campaign—is yet another buffoonish political opportunist with a perplexing blond haircut. What’s all this mean? Here’s your primer on the potential crackup in the Old World.

So Britain is thinking about getting a divorce from Europe. Sounds sad.

Indeed. The slow but steady integration of Europe into a politically and economically unified bloc following the genocidal madness of World War II was one of the great diplomatic triumphs of the 20th century. Now, Britain and Germany are barely sleeping in the same bedroom.

No country has ever left the EU before. And while nobody can say for sure what the consequences of Britain’s departure would be, some are worried it might encourage copycat referendums in countries, like the Netherlands, that also have an ambivalent relationship with the rest of Europe. That sort of domino effect is the stuff of nightmares in Brussels. “As a historian, I fear that Brexit could be the beginning of the destruction of not only the EU but also of Western political civilization in its entirety,” European Council President Donald Tusk has said, perhaps a touch melodramatically.

Even if other nations didn’t follow U.K.’s lead out the door, a Brexit would almost certainly weaken the EU, which has already been battered by the euro crisis and pervasive economic stagnation. We’re talking about the possible subtraction of the world’s fifth-largest economy, not to mention an important nuclear power, from the European project. It’s not a pretty prospect. (Oh, and there’s a strong chance that pro-Europe Scotland would try to secede from Great Britain again, so we’re talking about the possible dissolution of the U.K. as we know it, too.)

Any chance it’s actually going to happen?

The polls are tight. Last week, the British public slightly favored leaving. This week, it slightly favors staying (44 percent to 43 percent, in the latest Sunday Times survey). Voters may have been given pause by the shocking murder of Jo Cox, the young, pro-Europe member of Parliament who was shot and stabbed to death by an apparent right-wing extremist on Friday. But it still feels like the referendum could go either way.

What’s the argument for Brexit?

Well, there’s a polite case suitable for, say, an afternoon teatime discussion. And then there’s a wild-eyed, xenophobic case. Which do you want to hear about first?

Let’s start with the polite case.

All right then. First, a little context. The British electorate has long had mixed feelings ’bout European unity. It likes free trade—in 1975, 67 percent of the country voted to remain in what was the Common Market, a precursor to the EU— but dislikes ceding too much control to Brussels. The U.K. has never adopted the euro—a move that has proven wise in light of recent events—and, with its large financial sector, it is a bit fonder of untrammeled free market capitalism than Germany and France. Most Brits would still probably respond to the idea of a full-blown United States of Europe with Margaret Thatcher’s famous words: “No, no, no.”

Mass immigration has also triggered a great deal of anxiety in Great Britain. Net migration into the U.K. has roughly doubled since 2000, thanks entirely to new arrivals from other EU nations, particularly central European countries like Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania. There’s little Britain can do to stop the influx because the EU’s rules more or less require open borders between member states (specifically, countries have to welcome any EU citizen who comes looking for work). This has all led to complaints that immigrants are diluting authentic British culture and taking jobs from natives, as well as concerns that foreigners are putting pressure on housing prices and social services, like the National Health Service. A YouGov poll found 71 percent of British people thought immigration had been too high over the past 10 years, and 63 percent wanted stiffer limits. The Syrian refugee crisis, and the focus its put on Muslim immigration, has probably intensified all these frustrations by mixing them up with fears about national security.

The leave campaign likes to say that Britain needs to separate itself from the EU now in order to “take back control” of its laws and its borders (its official website URL is voteleavetakecontrol.org). In its telling, the unaccountable bureaucrats in Brussels have burdened British businesses with needless reams of red tape while porous EU borders have encouraged all of that uncontrolled immigration. Worst of all, these problems are bound to intensify as Europe pursues its goal of an “ever closer union.” Leaving now would give U.K. citizens back their own sovereignty, while also saving Britain the money it spends every year on its EU membership dues, which could be used instead on tax breaks and NHS funding. All of this should sound familiar to Americans.

“Staying in the European Union as it evolves towards an ever more centralized, federalist structure in an effort to preserve the euro is the risky option,” Johnson, a member of Parliament and former mayor of London, has said. “The best thing for us now because we’re a great country, a proud economy, a proud democracy, is to take back control over our borders, over the huge sums of money that we send to the European Union, and to take back large amounts of control for our democracy.”

Of course, leaving the European Union has an obvious downside: It means abandoning one of the world’s largest free trade zones, which could hurt British exporters, especially its all-important banks. Pro-Brexit campaigners argue this wouldn’t be a problem—Britain would simply strike new free trade deals with its old compatriots in Europe, which surely would want to continue selling goods in the U.K.(BMW would like to keep selling its cars to London’s financiers, after all.) For potential models, they typically point to Norway and Switzerland, both of which have free trading relationships with the EU despite not technically being members. Best yet, supporters say, leaving would also free up British lawmakers to seek trade deals with other fast-growing economies, without being hamstrung by Europe.

Responding to concerns about trade, Johnson has said: “This is like a jailer has accidentally left the door of the jail open, and everybody can see the sun and the land beyond. And everybody is suddenly wrangling about the terrors of the world outside. Actually, it will be wonderful.”

In short: The British people will reclaim what’s rightfully theirs, cut down on immigration, and strike great trade deals. This should sound familiar, as well.

OK, that’s a little Trumpish. But what about the crazy xenophobia?

Remember, what I said about anxieties over immigration and Muslims and national security?

Vaguely.

Here’s an ad produced by the official leave campaign.

Vote Leave

Oh. Damn.

Note that it doesn’t even have to say why Turkey joining would be a problem. That’s implicit. But, just in case, some of the campaign literature produced by team Brexit spells things out:

Since the birthrate in Turkey is so high, we can expect to see an additional million people added to the U.K. population from Turkey alone within eight years.

This will not only increase the strain on Britain’s public services, but it will also create a number of threats to U.K. security. Crime is far higher in Turkey than the U.K. Gun ownership is also more widespread. Because of the EU’s free movement laws, the government will not be able to exclude Turkish criminals from entering the U.K.

Now, here’s a prominent graphic from the Vote Leave website.

Vote Leave

I’m sensing a theme.

Yep. It’s worth noting that Turkey is, in fact, many years away from implementing all the laws and regulatory changes it would need to in order to join the EU, and then, even if it did, Britain’s own Parliament would have to approve the treaty, as the BBC points out.

And now here’s a riff on the Syrian refugee crisis:

Daniel Leal-Olivas/Getty Images

At the risk of violating Godwin’s law, observers have made some compelling comparisons between this bad boy and actual Nazi propaganda.

But in fairness, even members of the official leave campaign condemned this particular image. The man standing in front of the flatbed is Nigel Farage, head of the anti-immigrant U.K. Independence Party, which is sort of the id of the whole Brexit movement. Boris Johnson tends to say he’s pro-immigration but thinks it needs to be reduced to levels that are in keeping with the needs of British business. (He never explains precisely what those levels are.) Farage, by comparison, is happy to talk about the threat of Romanian crime waves and how you don’t hear English spoken on British trains anymore. He’s also claimed he’d be content with lower economic growth if it meant fewer immigrants. “I think the social side of this matters more than pure market economics,” he said.

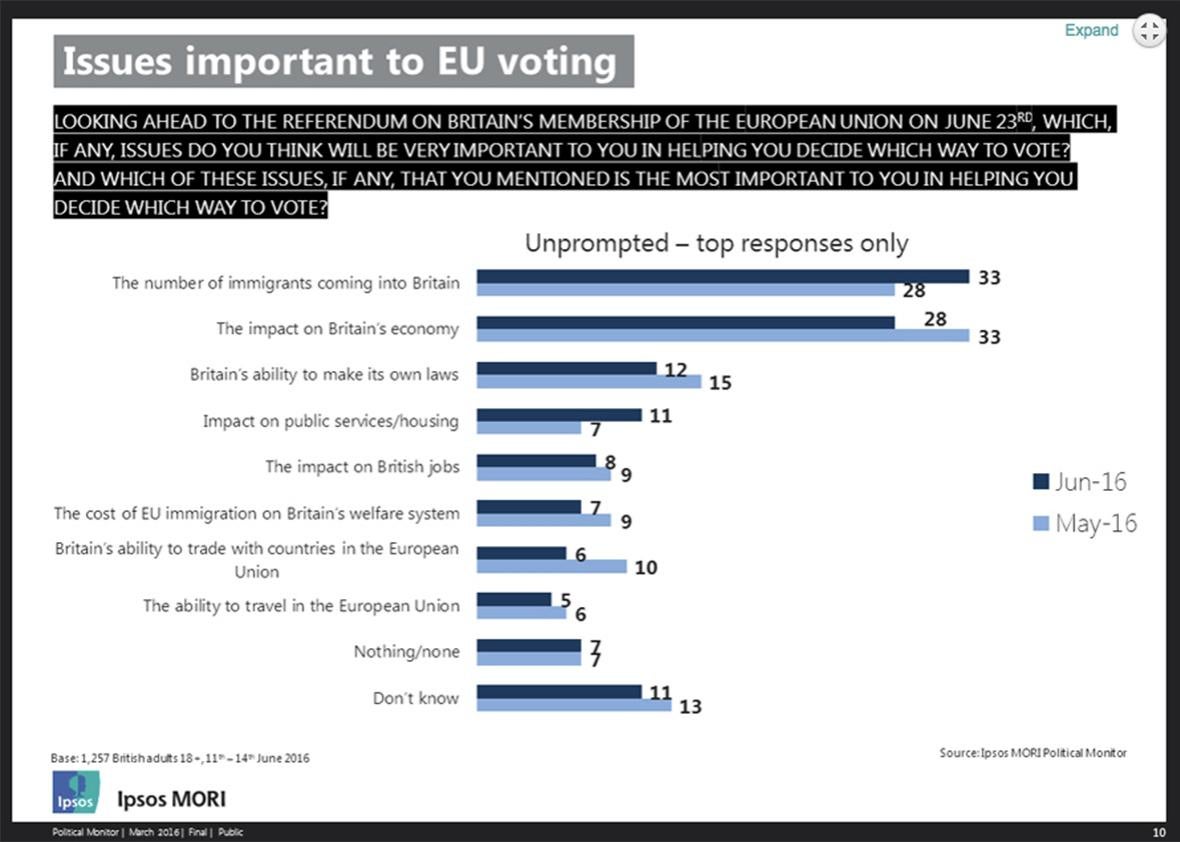

Notably, when pollsters ask voters why they want to leave the EU, immigration tends to top the list of explanations. More than 40 percent of those in favor of exit told YouGov immigration was the most important reason. An Ipsos MORI poll last week found a similar result: Among all voters, 33 percent cited “the number of immigrants coming into Britain” as one of most important factors behind their decision; only 28 percent said the economy.

Ipsos MORI

What’s the case for staying in the EU?

The remain camp tends to point out that immigration is probably a good thing for the U.K. economy overall—that without it, Britain would be an aging society with lower population growth, which is hard to sustain—and that for all the worries about an influx of job-thieving Poles, British employment rates are actually at all-time highs. They also note that, complaints about red tape aside, Britain is pretty lightly regulated relative to its global peers and that the leave campaign enormously exaggerates how much money Britain could save on EU contributions: Boris Johnson & Co. like to claim that the country currently sends 350 million GBP a week to Brussels, when in fact the real number is probably closer to 136 million GBP.

But mostly, those who would like to stay in the EU argue that leaving could tank Britain’s economy by cutting it off from its trade bloc. An analysis by the U.K. Treasury suggested that leaving would shrink the country’s gross domestic product 6.2 percent by 2030—or, to put it another way, “Britain would be permanently poorer by the equivalent of £4,300 per household.” That may be exaggerated, but most economists—the Financial Times polled more than 100 of them—seem to agree with International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde that the likely outcomes for Britain would range from “pretty bad to very, very bad.”

Again, the issue boils down largely to trade. Around half of British exports go to the EU. And it’s not all that clear what kind of deals the U.K. could sign with Europe that would also allow them to clamp down on immigration and dump pesky regulations. After all, the EU probably has every reason to make an exit unappealing for other countries, lest they consider a similar move of their own. What about Norway and Switzerland? Their examples aren’t necessarily that encouraging. As a member of the European Economic Area, Norway still has to abide by EU rules and regs, including those that touch on European immigration, and pay its own membership fees to Brussels. At the same time, it doesn’t get any official input in EU affairs, putting it in the awkward position of “regulation without representation.”

As Politico notes, “The Norwegian Parliament adopts five EU laws for every day it is in session, without having much say in how those laws are formed.” (Norway’s prime minister, notably, has warned that the U.K. would probably regret a Brexit). As for Switzerland, it manages to get by with 120 different bilateral treaties between itself and EU member states—a system the technocrats in Brussels dislike and probably aren’t eager to see reproduced. Swiss voters did pass a referendum in 2014 meant to limit EU immigration—they’re also ticked about Polish migrants—but it’s controversial and may violate the country’s treaty obligations on the free movement of people. Bottom line: It’s hard to imagine Britain happily following Norway’s or Switzerland’s model.

As German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble put it:

“That won’t work. It would require the country to abide by the rules of a club from which it currently wants to withdraw. If the majority in Britain opts for Brexit, that would be a decision against the single market. In is in. Out is out.”

If Britain can’t get a new free trade deal with Europe, it would be able to fall back on World Trade Organization rules governing tariffs and the like. Those aren’t terrible—lots and lots of trade happens under the WTO banner—but it’s worse than what they have now. As for deals with other countries? Well, President Obama, who has encouraged the British people to remain in the EU, has said it could take five or 10 years for the U.K. to negotiate a pact with the United States.

Boris Johnson, for his part, responded to this by dredging up the rumor that Obama removed a bust of Winston Churchill from the Oval Office “as a symbol of the part-Kenyan President’s ancestral dislike of the British empire.”

Matt Frost/Getty Images

What’s this Boris Johnson guy’s deal, anyway?

This is Boris Johnson. He is a former newspaper reporter and magazine editor who turned to politics and was eventually elected mayor of London, during which time he became a sort of beloved clown who obliterated buttoned-up British norms—the most famous image of the man is from the moment he got stuck on a zip line during the London Olympics and dangled above the crowd jovially waving two tiny British flags.

He’s also a conservative financial industry booster, and in the past has had a habit of doing things like jokingly referring to gay people as “tank-topped bumboys” and black people as “piccaninnies” with “watermelon smiles.” Finally, he’s deeply ambitious, and by most accounts would like to nab David Cameron’s job as prime minister—which could easily happen if Britain votes for an exit. That may have something to do with why he seemingly switched his position on the issue back in February.

On the bright side, Johnson inspires some wonderfully colorful insults. My favorite, from the Guardian: “He’s a [sic] egotistical twit in a child-sized Sia wig who keeps filling London with insane foreign-owned monuments to his own genitals.” A close second: One rival compared him to “Donald Trump with a thesaurus.”

Screenshot via Financial Times

Who actually supports Brexit? And who wants to stay?

Again, the breakdown on this is going to remind you a whole lot of how the U.S. has split on Trump. This Financial Times graphic is the best summary I’ve seen. Liberals, people younger than 40, those with college degree, and London residents—along with the Scottish and Welsh—tend to support staying in the European Union. Older, conservative, less-educated voters would prefer to leave. It really is a clash between Britain’s cosmopolitan youth and its older working class.

So, what actually happens if Britain votes to leave on Thursday?

It’s not entirely clear. The European Union’s treaties don’t really spell out in detail how member states can secede because they’re not supposed to. But it will probably trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, which requires the EU to negotiate a “withdrawal agreement” with the state in question. Britain and the EU would have at least two years to hammer out their separation.

Meanwhile, the markets will likely freak out, like they always do over sudden political uncertainty. This isn’t the nightmare scenario, thankfully. Far worse would be a divorce with a country that actually uses the euro—Spain, for instance—which would threaten to unravel the all-important currency union, calling into question the massive amounts of euro-denominated debt held by investors and banks around the world. Now that would be a disaster.

Nonetheless, the Brexit campaign has mixed some sincere concerns about democracy and state sovereignty with the nativism of certain voters, who seem to feel their country is slipping from their grasp in the 21st century. It’s featured politicians who’ve peddled sunny predictions about Britain’s economic future outside the EU while remaining conspicuously light on the details of how that will be achieved. None of it’s encouraging. But again, it’s all pretty familiar.