On April 11—as lawmakers began to weigh impeachment charges against Brazil’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff—the country’s vice president sent a curious recorded message to a group of legislators. In a 15-minute “address to the nation,” Michel Temer spoke as if he had just taken office as president. In a somber tone, he implored all Brazilians to pull together and face the challenges ahead.

The speech was comically premature. Aides would later claim that he had just been practicing on his cellphone and accidentally hit “send.” In any case, to many Brazilians it was clear evidence that he was conspiring to take his boss’ job.

Almost exactly a month later, that’s exactly what he did. The Senate opened the impeachment trial against Rousseff on charges that she violated budgetary and fiscal responsibility laws; in the meantime she has been suspended from office for 180 days. In accordance with the constitution, the vice president takes over on an interim basis.

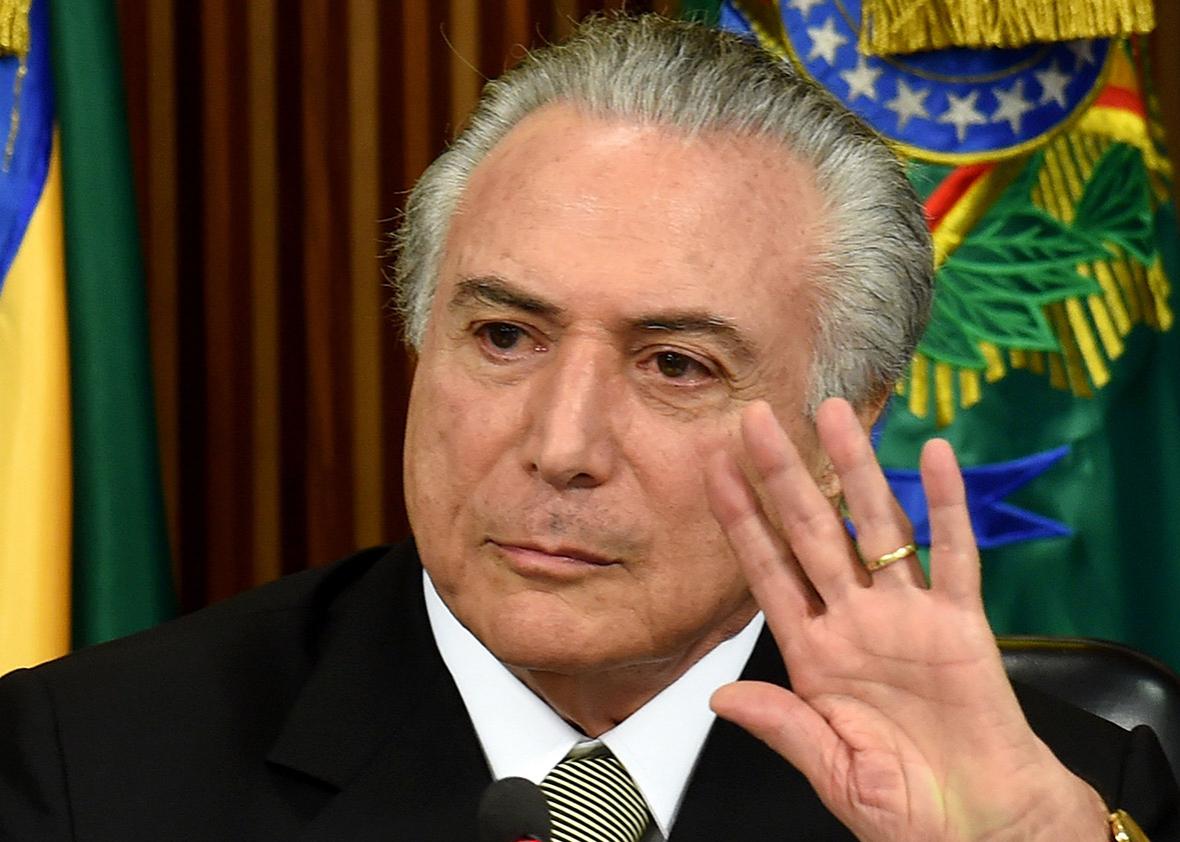

The 75-year-old Temer—whose last name means “to fear” in Portuguese—has been a supporting cast member in Brazilian politics for decades. The son of Lebanese immigrants, he was first elected to Congress in 1987 during the transition from dictatorship. Although he has recently been portrayed as a right-wing conservative, in truth he and his party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, or PMDB, defy all political labels. Forged in the late 1970s as an officially recognized opposition party to the military government—one of its many nods to Brazil’s long transition to democracy—the party was defined by the single-minded fight for direct elections. Since then it has become a big tent with few ideological tenets and devoid of any real convictions. The PMDB has played the perpetual power broker, forming a backbone of governing coalitions of all political stripes for the last two decades.

Temer, a constitutional law expert and respected lawyer, is a product of the rough and tumble world of Brazilian politics. Marriages of convenience are his forte. He worked just as closely with centrist President Fernando Henrique Cardoso from 1995 to 2002 as he did with the leftist Workers’ Party government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva from 2003 to 2010. Already an ally of Rousseff—who would become Lula’s handpicked successor—Temer negotiated a space on her ticket in 2010. The two reportedly remained close until shortly after re-election in 2014 when the economy spiraled into crisis and an explosive, multibillion-dollar corruption scandal around the state oil company, Petrobras, implicated much of Brazil’s elite. Rousseff has never been named in the allegations, but she is one of the few. Dozens of political and business leaders have been arrested—including members of Rousseff’s party and inner circle. While the impeachment charges are unrelated, the wave of discontent spurred by the scandal, coupled with a sharp economic decline, is what sank her presidency.

Temer has spent most of his career as a consummate operator, a regular figure but never in the spotlight. His success was driven through deal-making and backroom negotiations. Reports have emerged that Temer met with the U.S. Embassy in Brasilia multiple times though his career, providing secret political briefings and insight. He has allegedly been quick to use leaked statements and letters to further his aims. When he was speaker of the House, he met personally with every member of the 513-seat body, maintaining wide networks of close relationships. This lurking behind the scenes led one rival to label him the “butler in the house of terror.”

Now, his decisions to abandon Rousseff, push for impeachment, and seize the presidential limelight for himself sets up an interesting experiment: What happens when the kingmaker takes the throne?

To be sure, the challenges ahead of him are enormous. Brazil’s economy is in freefall, contracting by almost 4 percent in 2015 and expected to perform just as poorly this year. Economic reforms, which stalled under Rousseff, are badly needed, as Temer well knows. In fact, commitment to fiscal responsibility is the PMDB’s stated reason for abandoning the coalition with Rousseff’s Workers’ Party.

Still, to pass reforms he will have to put his political maneuvering skills to their greatest test. First and foremost, he must earn legitimacy beyond simply replacing the deeply unpopular Rousseff. Many on the left in Brazil and elsewhere are outraged, claiming the impeachment is illegal and a coup d’état against the country’s legitimate president. Though the impeachment has adhered to constitutional procedures, Temer’s governing mandate is thin. His decision to name an all-white, all-male Cabinet—after ousting the first female president in one of the world’s most diverse countries (over half of Brazilians identify as black) was at least troublingly tone-deaf, if not an ominous sign for democratic representation, and hardly conducive to building the support his agenda desperately needs. Most experts agree that his choices, many of whom are under investigation for corruption, were made with an eye only to building support in Congress. This strategy has already backfired: On Monday an explosive tape leaked of planning minister Romero Jucá plotting Rousseff’s impeachment as a way to stop the corruption investigations. “We have to change the government to be able to stop this bleeding,” he said. Jucá resigned immediately; he had been in office for only 10 days. It may be that Machiavellian deal-making prowess in the legislature doesn’t necessarily translate to the presidency, especially in Brazil’s new context of transparency and accountability.

Temer must also tackle his own legal problems, which are potentially even more serious than his predecessor’s. Unlike Rousseff, Temer has been accused of involvement in some of the corruption scandals that have exposed Brazil’s seedy underbelly, including a fine for campaign finance violations. Other members of the PMDB—among them suspended speaker of the House Eduardo Cunha and President of the Senate Renan Calheiros—are chief suspects in the Petrobras investigations. His pick for party whip in the House is currently being investigated for attempted murder. Brazilian voters have taken notice—Temer’s approval ratings are even lower than Rousseff’s. One pre-impeachment poll found a mere 2 percent of Brazilians would vote for him in new elections.

Even with all of these challenges, many are hopeful that Temer will be able to make quick progress on economic issues and build political legitimacy as he goes. Given the gravity of the situation, he may be given the benefit of the doubt for long enough to make an impact through fiscal reforms, austerity measures, and other changes forced through a friendly Congress. In all of this, low expectations could serve to his advantage.

And at the very least, as new Foreign Minister José Serra made clear in a speech this week, Brazil’s foreign policy seems set to become more open to trade and foreign investment, much to Washington’s delight. Considering Temer’s personal life—thrice-married, currently to a former beauty queen 42 years his junior—this new diplomatic chemistry between the U.S. and Brazil may grow even stronger after November. But only if the presumptive Republican nominee ends up occupying the White House.