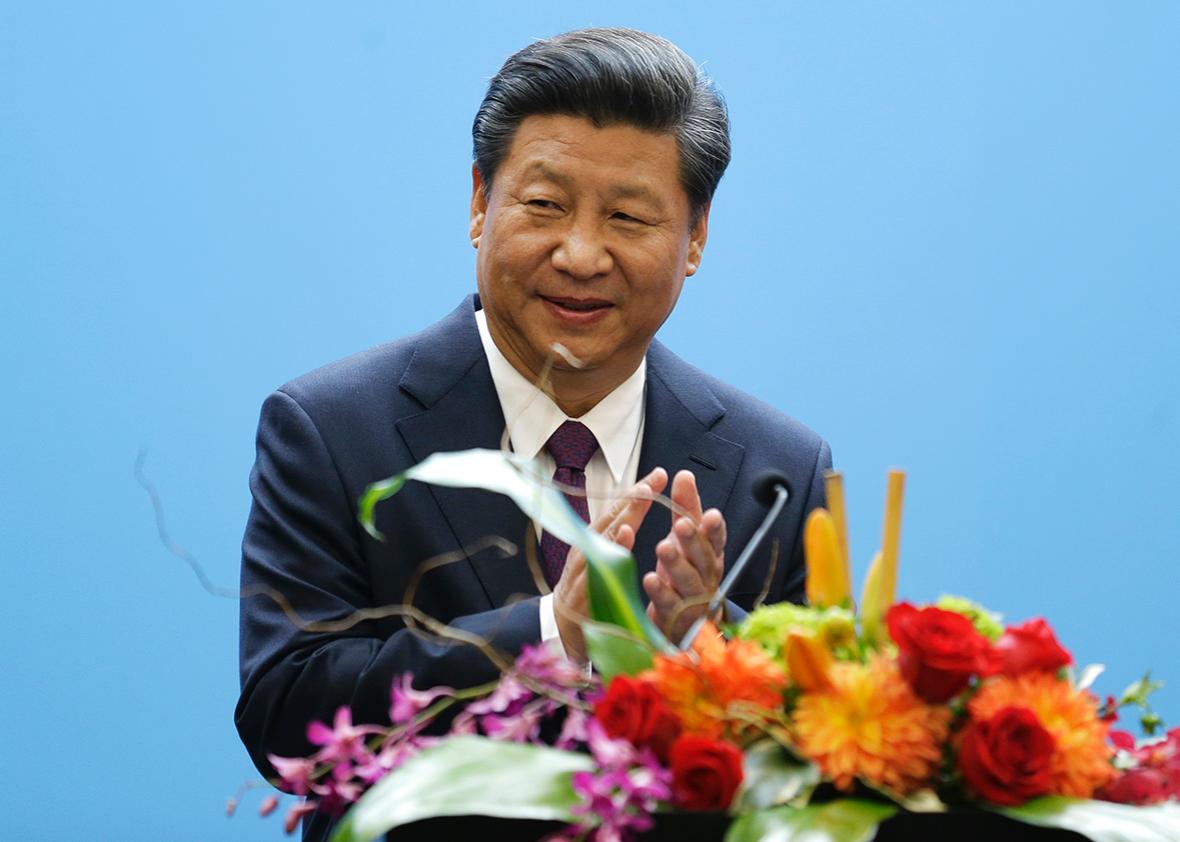

When Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in Seattle on Tuesday for his U.S. visit and joked that his anti-corruption drive was no House of Cards power play, he wasn’t just showing his familiarity with American pop culture: He was adding a page in a PR playbook that goes all the way back to Deng Xiaoping. In 1979, when Deng became the first Chinese Communist Party leader to visit the United States, he took pains to make a good impression and seem relatable to American audiences. He shook hands with Harlem Globetrotters, climbed on NASA’s lunar rover, and, most memorably, donned a gigantic cowboy hat at a Texas rodeo, delighting the crowd.

Xi seems to be even more determined to show how much he “gets” America. His opening remarks on Tuesday were replete with American cultural references. Besides nodding to Frank Underwood’s machinations, Xi offered a (somewhat dated) shout-out to Sleepless in Seattle before checking off a long list of American literary luminaries he claims to enjoy, including Twain, Thoreau, Whitman, Jack London, and especially Hemingway, whose fondness for mojitos, he claims, led him to try one in Cuba. He also claims to take inspiration from the lives and ideas of American statesmen like Lincoln, Washington, and Franklin Roosevelt

Jiang Zemin, Deng’s successor, took up this act during his 1997 visit that sought, in part, to get Americans to stop associating his government with soldiers killing civilians near Tiananmen Square in 1989. Jiang sported a three-cornered hat at Colonial Williamsburg, and made a point of speaking what the New York Times called “broken but charming English.”

Xi has proved adept at this sort of soft-power diplomacy—never a strong suit of his predecessor, Hu Jintao. In 2012, on a U.S. tour showcasing him as leader-in-waiting, Xi’s itinerary was full of symbolically aren’t-we-all-alike people-to-people moments. He visited Muscatine, Iowa, where he stayed as part of a 1985 delegation, and spent time with his former hosts. And he had his own special sartorial photo-op: After repeatedly emphasizing his love of basketball, Xi was given an L.A. Lakers jersey bearing his name.

But it’s important to note that Xi doesn’t reserve this routine only for American audiences. China’s leader is a promiscuous name-dropper wherever he goes. When he was interviewed in Sochi during the 2014 Winter Olympics, he provided a laundry list of Russian authors he admired: “Krylov, Pushkin, Gogol, Lermontov, Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Nekrasov, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, [and] Sholokhov.” In France a month later, Xi had a similar list handy of French figures: Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Saint-Simon, Fourier, Sartre, Montaigne, La Fontaine, Molière, Stendhal, Balzac, Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas fils, Maupassant, Romain Rolland, and Jules Verne. In Germany he noted his fondness for Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, Feuerbach, Heidegger, and Marcuse and spoke of the “enchanting melodies by Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, and Brahms.” In Mexico he paid tribute to “Diego Rivera, the master of contemporary art, and … Octavio Paz, the towering figure in literature.” And so on.

So we probably shouldn’t make too much of Xi professing a deep appreciation of The Federalist Papers or Common Sense, let alone think that he actually admires their subversive implications for his political system. Xi could not possibly have been deeply affected by (or even read) all the authors he mentions. Those references simply function, as does his saying he is a fan of the Lakers and The Old Man and the Sea as proof of his cultural cachet in the host country du jour.

There are bigger problems with thinking of Xi as the leader next door, who just happens to be an ocean away. No matter how well he seems to grasp American culture, he doesn’t share its values; after all, Deng’s cowboy hat didn’t prevent him from sending in tanks in 1989. Xi likes to speak of the “Chinese dream,” a phrase that clearly evokes the American dream. But Xi’s dream is nothing like the American version. The American one celebrates individuals and families bettering their lots through their own hard work and determination, whereas the Chinese one extols a nation’s return to glory.

Xi has a richer array of shared cultural symbols to play with in America than Deng had—House of Cards is hugely popular in China, too—but he also faces greater challenges. In 1979 many Americans were curious about a China that seemed to be making a fresh start. Now there are successive sets of negative images—including Chinese censorship, crackdowns on lawyers, feminists, and NGOs, computer hacking, currency devaluation—that sour American views of China. There are limits to how much citing one’s love for Hemingway can do to change that.