At least 40 years ago, back when the Soviet Union still existed and the Berlin wall still stood, the KGB searched the apartment of a Russian friend of mine. Inevitably, they found what they were looking for: His large collection of samizdat, illegally printed magazines and books. They pounced on it, rifled through it—and then one of them held up my friend’s contraband copy of Robert Conquest’s most famous book, The Great Terror. “Excellent, we’ve been wanting to read this for a long time,” he declared. Or words to that effect.

Nowadays, it’s difficult even to conjure up the background necessary to explain that scene. Can anyone younger than 30 imagine a world without satellite television and the Internet, a world in which television, radio, and borders were so heavily patrolled that it really was possible to prevent a very large country from reading a single book? It was also possible to control and distort that country’s history, so much so that its own citizens were unable to find out the truth from their own writers, in their own language. In the Soviet Union, there was always a vast gap between the official versions of the past and the stories that people knew from their parents and grandparents. That gap made people curious, hungry to know what really happened—even people who worked for the KGB.

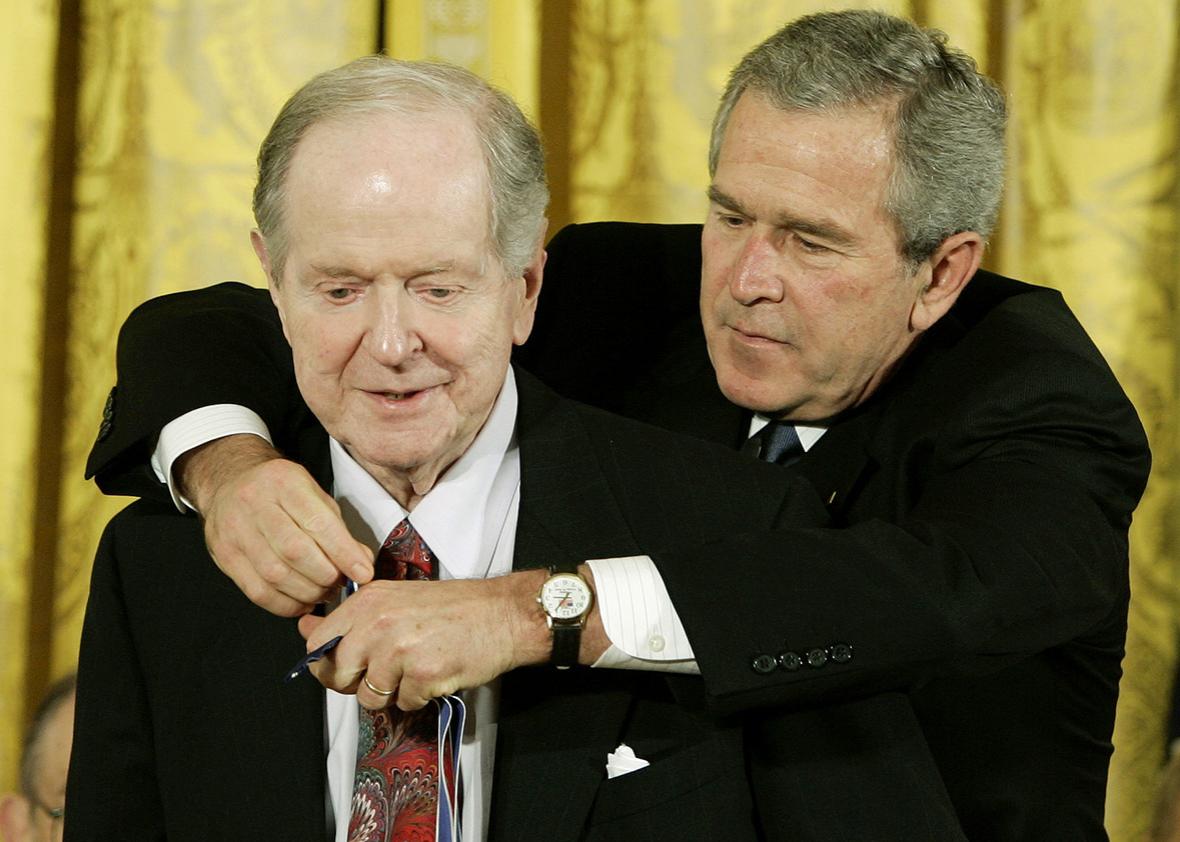

From the 1940s onward, Robert Conquest, who died this week at 98, dedicated his life to filling that gap. He first visited the Soviet Union in 1937 (as I once heard him tell an incredulous group of much younger scholars) and then spent much of the war as a British intelligence officer, working on Bulgaria. During that time, he came to loathe not only the crimes of the regime but the lies it told about itself, especially when they were repeated in the West.

Soviet history wasn’t his only passion. He was also a poet; the title of his unfinished memoir was Two Muses. Unsurprisingly, his two most important books—The Great Terror, the story of Stalin’s purges and show trials, and The Harvest of Sorrow on the orchestrated Ukrainian famine—are as outstanding for their insights into human behavior as for the facts they assembled. In part, this is because Conquest listened to, and quoted from, the émigrés and defectors who were at the time often dismissed as “biased”: They didn’t understand great power politics, or they bore grudges, or they didn’t understand that they were unimportant casualties on the road to the communist utopia.

“You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs,” said Stalin’s apologists. But Conquest relied on history’s casualties to explain, for example, why so many people in Stalin’s Soviet Union confessed to crimes they did not commit. In The Great Terror, he quoted a prisoner: “After fifty or sixty interrogations with cold and hunger and almost no sleep, a man becomes like an automaton—his eyes are bright, his legs swollen, his hands trembling. In this state, he is often convinced he is guilty.” Over the past two decades, archives have made it possible to write about Stalinism in different and more precise ways. But they also show that the defectors and émigrés got the outline of the story right—and so did Conquest.

Nowadays, it’s much harder to stop books from crossing borders. Ideas and information can travel at the speed of a mouse click. But that hasn’t stopped authoritarians around the world from trying to distort facts and history in whole new ways. Some try to control the Internet: The Great Firewall of China filters not only what Chinese readers can see but what they can search for in the first place. Others use disinformation, swamping the Internet with fake stories: Following the downing of MH17 in eastern Ukraine last year, the Russian regime concocted not one lie about the accident but dozens, each one more absurd than the next. It’s no longer possible to fight against a big lie with a single book. But the world needs the creativity and the courage of Robert Conquest more than ever.