“I’m a farmer,” Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera told reporters the first time he was arrested in 1993. The second time he was caught, in 2014, he reportedly admitted to Mexican journalist Carlos Loret de Mola that he had killed 2,000 or 3,000 people.

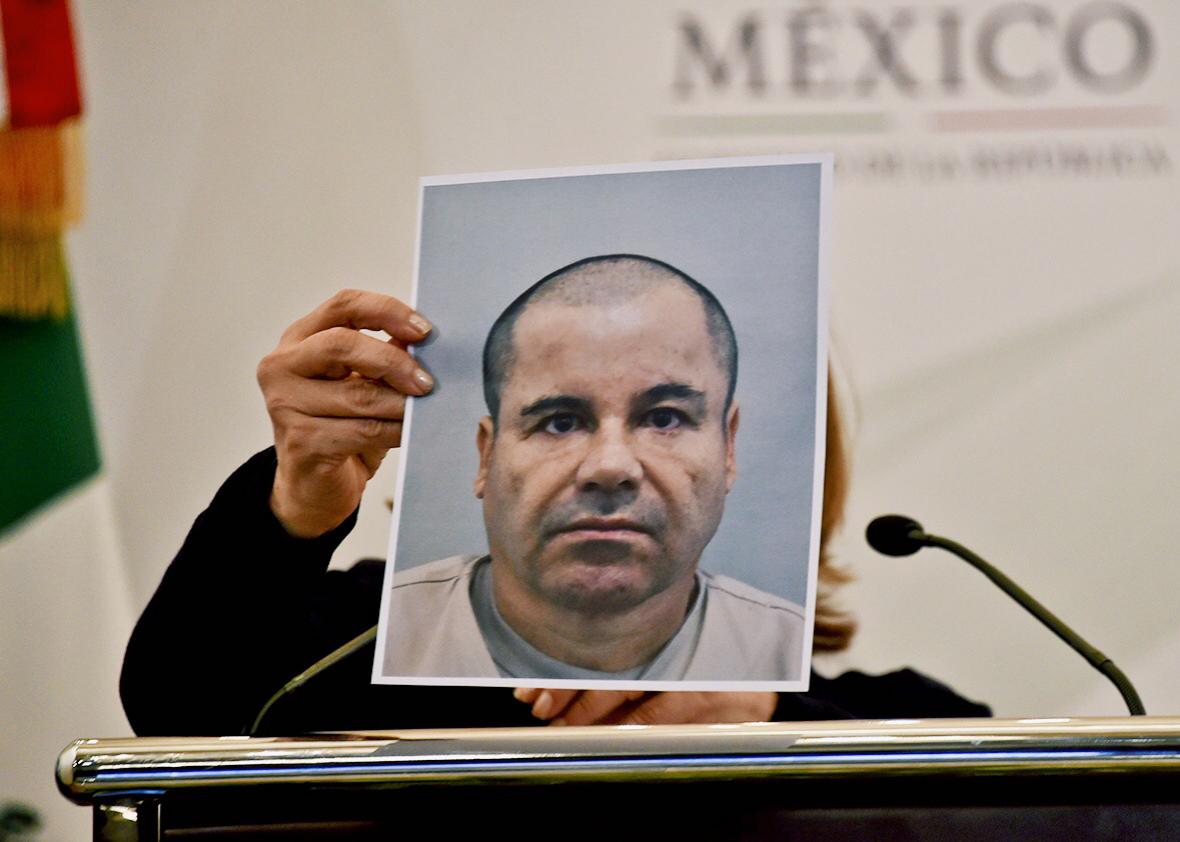

Chapo is Mexico’s most-wanted drug trafficker. On Saturday night, he escaped from a maximum-security prison for the second time.

It’s impossible to know what’s going on inside Chapo’s mind. The first time he escaped prison, in 2001, he fled in a laundry cart and drove out of the prison grounds in the back of a car, if the official version is to be believed. This time, he managed to construct a 1.5 kilometer tunnel in plain sight of the authorities. It’s unlikely that his plans ended with him stepping outside of a pipe. Odds are Chapo has planned his next steps carefully. The question is whether he’ll try to hide—perhaps disappear into the mountains of Sinaloa, from which he hails—and “retire” from his days as a murderous criminal kingpin, or whether he’ll seek to rebuild his Sinaloa cartel as Mexico’s preeminent drug trafficking organization.

The Sinaloa cartel is considered Mexico’s oldest cartel and, until about 2011, its strongest. It has expanded its reach globally, according to U.S. authorities. It has long been run by various bosses under the direction of Chapo and his right-hand, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada. But distrust began to consume the cartel’s leadership in May 2007 when a random traffic stop in Chicago led the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to the cartel’s key representatives in the Midwestern city, the Flores brothers. The Beltran Leyva brothers, three top Sinaloa cartel bosses who worked with Chapo, were suspicious of the Flores brothers, according to transcripts of phone conversations submitted in federal court in Chicago. The Sinaloa leadership apparently wasn’t in agreement over whether the Flores brothers were trustworthy enough to handle the vast amounts of heroin that the U.S. market required. Chapo, in addition, was annoyed at the Beltran Leyvas for flaunting their wealth in Sinaloa’s capital, Culiacan, according to local journalists and authorities. These tensions and disagreements reportedly began to cause fissures within the criminal enterprise.

Chapo has always been known for being discreet, never showing off his wealth and quietly going about his business, albeit with the ruthlessness one might expect is required to run such an organization. According to testimony of one alleged former employee, Chapo once learned that one of his drug distributors had lost money on a shipment. He was livid, according to the witness, and ordered a meeting in which the offending distributor would be reprimanded. Chapo and his lieutenants gathered in a house and discussed the mistake with the employee. When it was done, they picked up their guns and left the room. The matter appeared settled. Then, as the distributor walked out, one of Chapo’s hit men put a bullet in the back of his head. “One of his strengths is his tolerance for frustration … revenge is not something that he exacts with the immediacy of an impulsive person,” reads a psychological analysis of the drug kingpin conducted by the Mexican authorities.

Rumors abound of Chapo drinking whiskey and enjoying the company of several women at a time, but those have remained largely unfounded. He has married four times, and had lovers, but according to most media reports and testimony, he hasn’t had a tendency to stray during relationships. During his first stint in prison, he constantly wrote gushy love letters to a female inmate, Zulema Hernandez, who paid him conjugal visits, according to guards’ testimony.

“Hello, my life! Zulema, my dear,” Chapo wrote on July 17, 2000, according to Mexican newspaper reports. The authorities were apparently planning to transfer his paramour to another correctional facility. “I have been thinking of you every moment and I want to imagine that you are happy … because your transfer will soon take place. … The other prison will be much better for you, because there will be more space, more movement and time on the days that your family visits. … When one loves someone, as I love you my heart, one is happy when there’s good news for this person who one adores, even though I will be more emotional for the days following your transfer.” He signed the letter simply “JGL.”

In late 2008, Zulema was found dead in Mexico City, a big Z carved into her buttocks. The Z stood for Zetas, Chapo’s biggest rivals. Shortly before his capture in 2014, in spite of having married a 17-year-old beauty queen in 2007, the authorities learned that Chapo was still in regular communication with his first wife from decades before.

The feud between the Beltran Leyva brothers and Chapo escalated at the beginning of 2007. Random shootings in Culiacan became the norm, and, during my reporting trips there in subsequent months, I found the police had been unwilling or unable to investigate many of the murders. The cartel’s civil war, according to local reports and authorities, hit a point of no return when Edgar Guzman Loera—Chapo’s 22-year-old son who had been groomed to stay out of the drug trade—was gunned down in Culiacan on May 8, 2007 by Chapo’s rivals.

Since that day, dozens of key lieutenants in the Sinaloa cartel have been killed or captured. One Beltran Leyva brother was arrested and is serving time in Puente Grande prison, from which Chapo escaped in 2001; Mexican soldiers gunned another of the brothers down. A key Chapo lieutenant, a Texan named Edgar Valdez Villareal, aka La Barbie, was arrested. Local media speculated that Chapo had turned them all in, although this too was never proven.

The crucial catch for the authorities was the capture of Vicente Zambada-Niebla, the son of El Mayo, in March 2009. Zambada-Niebla was extradited to Chicago, where he secretly pled guilty and agreed to cooperate with the government. The plea deal remained secret for a year—until Chapo was captured in Feb. 2014 in Mazatlan, on the Sinaloan coast, leading to rampant media speculation that El Mayo and his son had ratted out their long-time partner in a deal with authorities.

So Chapo may have engineered a jailbreak, but does he even have a cartel to return to? El Mayo is still alive—and may or may not be a turncoat—but is 67-years-old. Mexican and U.S. authorities say that Juan Jose Esparragoza Moreno, a reputedly shadowy Sinaloa cartel leader who was said to negotiate pacts with other cartels at key moments, died of a heart attack in June 2014.

Which leaves Chapo with little to work with. Since the Sinaloa cartel’s splintering, various new trafficking groups have sprung up nationwide. The Zetas, a group of paramilitaries-turned-traffickers, continue to work Mexico’s east coast, in constant conflict with remnants of the Gulf cartel. Since 2008, when a bunch of thugs threw two hand grenades into an Independence Day crowd in the central Mexican city of Morelia, the younger generation of drug trafficking organizations have appeared to be more prone to violence for violence’s sake, throwing aside the traditional cartel modus operandi of ensuring business goes smoothly. Consolidating those groups under one umbrella would be a challenge for even a near mythological figure such as Chapo.

Since his humble beginnings as an uneducated boy from the hills of Sinaloa, Chapo has shown a relentless drive to survive and stay on top of the drug game. If he decides to rebuild his empire, the unfortunate likelihood is that many parts of the country will once again descend into bloodshed.