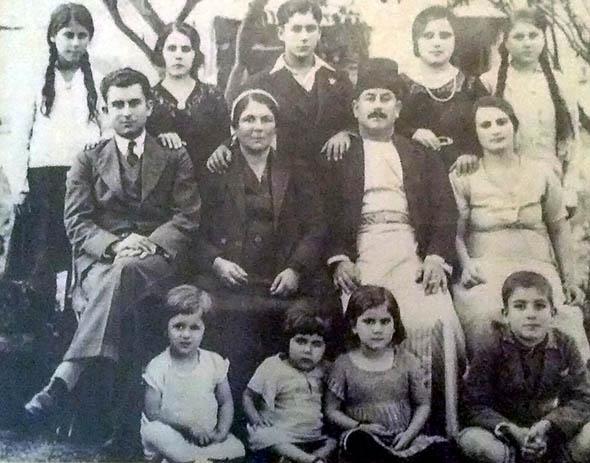

Every year, on May 15, I ask my grandmother to tell me the story of how she was made homeless. It happened 67 years ago. She was 14, the youngest of 11 siblings from a middle-class Christian family. They had moved to Haifa from Nazareth when my grandmother was a little girl and lived on Garden Street in the German Colony, which used to be a colony for German Templars, later becoming a cosmopolitan center of Arab culture during the British Mandate. When I ask her to recall what life in Haifa was like back then, her eyes fix on the middle distance.

“It was the most beautiful city I have ever seen. The greenery … the mountains overlooking the Mediterranean Sea,” she says, as her voice trails off.

My grandmother remembers clearly the night her family left. They were woken up in the middle of the night by loud banging on the front door. My grandmother’s cousins, who lived in an Arab neighborhood of Haifa, had arrived to tell them that Haifa was falling. The British had announced they were withdrawing, and there were rumors that the country was being handed to the Zionists. At the time, the German Colony had been relatively insulated from the incidents of violence in the rest of the country, which included raids and massacres of Palestinian villages by Zionist paramilitary groups. Yet the Haganah, a paramilitary organization that later formed the core of the Israel Defense Forces, saw the British withdrawal from Haifa as an opportunity and carried out a series of attacks on key Arab neighborhoods where my grandmother’s aunts and cousins were living.

“That night our Jewish neighbors told us not to leave,” my grandmother remembers. “And my father wanted to stay, to wait it out. But my mother … well she had 11 children, and of course she wanted us to be safe. And her sisters were leaving because of the attacks in their neighborhoods.”

Courtesy of Saleem Haddad

The family debated all night. In the morning, they reached a decision. They each quickly packed a small suitcase and left the rest of their belongings. “We hid the most valuable things we couldn’t take in a locked room in our house, thinking it would be safe until we came back,” she tells me, chuckling.

As the women of the family packed, my grandmother’s older brother, who had once been employed by the British forces, struck a deal, allowing them to leave on one of the last British vehicles withdrawing from Haifa. With what little they could carry, my grandmother’s family travelled to the Lebanese border, hiding in a British army vehicle.

When they arrived to Na’oura, on the border between Palestine and Lebanon, they were shocked to see so many other people from across the country. “It felt like the world had ended. The borders were overcrowded with cars and trucks full of people and belongings fleeing the violence. Others were leaving by sea.”

At the border they were ordered into a car, which drove through Lebanon for a few more hours. They were dropped later that night in Damour, a coastal town just south of Beirut. It was dark, they didn’t know anyone, and with no place to rest, the family of 13 slept on the streets in front of a supermarket, the dirty ground littered with rotting fruits and vegetables. As the sun rose the next day, they walked the streets of the unfamiliar town, recognizing friends and neighbors from Haifa who were also wandering the streets aimlessly. After hearing that Beirut was too crowded with refugees, they headed to Jezzine, in south Lebanon, where friends helped set them up in a tiny room in the home of some family friends.

“All summer we waited for news that we could go back,” my grandmother says. “By September, we realized there was little hope, and made plans to move to Beirut.”

For the next few years my grandmother’s family survived through the goodwill of friends and strangers, as well as through food parcels, given to them by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, which contained, among other things, powdered eggs, much to my grandmother’s fascination. Her older brothers eventually took up jobs in Beirut to support the family. My grandmother’s family was lucky on balance: As wealthier and Christian refugees, they were given Lebanese citizenship. However, the vast majority of Palestinian refugees were never naturalized, instead placed in one of the dozen UNRWA-operated camps in Lebanon, where they continue to live to this day.

My grandmother’s story is not a unique one. In 1948 Zionist militias depopulated and destroyed more than 530 Palestinian towns and villages. An estimated 750,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homes, and many who were unable to flee were massacred. By the end of July 1948 hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants from outside Palestine, many of whom were survivors of the Nazi Holocaust, had been housed in homes formerly belonging to Palestinian families like my grandmother’s. In December, the new Israeli state implemented a series of laws commonly referred to as the Absentees’ Property Law. These laws created a legal definition for non-Jews who, like my grandmother, had left or been forced to flee from Palestine. The laws allowed the newly created Israeli state to confiscate 2 million dunams (about 500,000 acres) of land from Palestinian families, including my own. In April 2015 the law was extended to cover land in the West Bank, thereby legalizing the continued expulsion of Palestinians and the confiscation of their land and property in order to house new Israeli citizens coming from abroad.

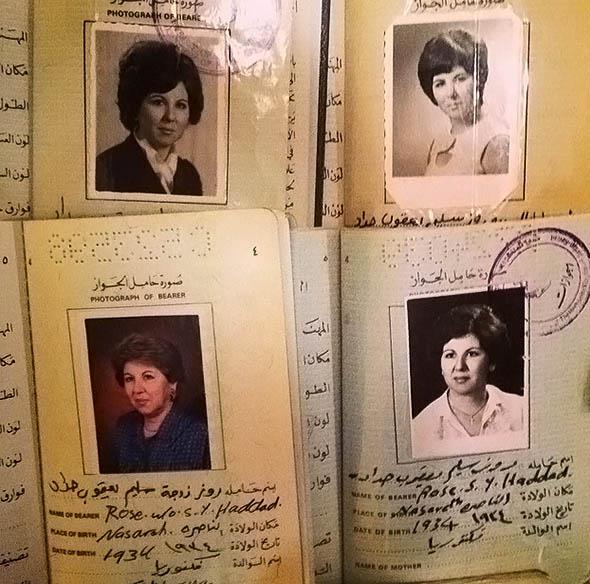

The uniqueness of what has become known as the Palestinian Nakba, or catastrophe, is partly the timing: It occurred at the dawn of state formation throughout much of Asia and Africa, which meant that hundreds of thousands of non-Jewish Palestinians found themselves stateless, unrecognized in the new world of postcolonial nation-states. Perhaps as a result, there is a joke that Palestinians collect passports obsessively, fearful that we might be stripped of one or the other. But is that really surprising given our history, that moment where the door was shut, leaving us on the outside, unrecognized—not just homeless, but stateless as well?

Courtesy of Saleem Haddad

In 1948, upon Israel’s creation, David Ben-Gurion, the founder and first prime minister of Israel, remarked that “the old will die, and the young will forget.” Given the centrality the Jewish tradition places on memory and the commemoration of struggle and suffering, Ben-Gurion should have known better. For the past 67 years, Palestinians have resisted the Israeli government’s continued efforts to erase the memories of trauma and resistance that began with the Nakba. To this day, Palestinians of my grandmother’s generation often wear the keys to their old houses around their necks, a sign that despite the dispossession of their land, their memories refuse to dim.

Every time my grandmother recounts her experience, a new memory emerges, and I add it to the story, embellishing it with new details and anecdotes. But as her memories made their way onto the page, I had a moment of self-doubt: In my grandmother’s recollection, she was clear that her family had made a decision to leave. Might this play into one of the myths used to justify the establishment of modern-day Israel on Palestinian land—the myth that, despite overwhelming historical evidence to the contrary, Palestinians left on their own free will?

“Are you sure you left voluntarily?” I ask my grandmother. “There was a war,” she replies.

“But no one kicked you out, yes? No one was directly attacking you?” I continue.

Courtesy of Saleem Haddad

“Not us personally, but my mother was worried by the reports. We thought we would be gone for a few weeks at most.”

Could my grandmother’s memory of the Nakba bolster the false narrative that Palestinians voluntarily left, given that her family had not been physically removed from their home? As I considered this, my thoughts began to coalesce around two points. The first—which seems particularly poignant in 2015, as boats of Arab and African migrants sink off European shores—is a question: What constitutes voluntary displacement? On May 15, 1948, in the face of growing hostilities and the threat of a regional war, my great-grandmother did the only thing she knew to protect her children: She left. Does running away from an imminent war, with a small suitcase and plans to return, constitute a voluntary departure? And if so, is the departed then unentitled to the land and belongings they left behind, and forbidden from ever returning?

My second thought centered on the politics of memory in war. In his novel, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Milan Kundera writes: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Israeli politicians hope that, given enough time and pressure, Palestinians will forget and accommodate themselves to their loss. This remains true to this day, as the Israeli state consolidates its occupation, constricting the remaining Palestinians into ever-shrinking ghettos.

Meanwhile, the collective Israeli memory of the Nakba continues to ignore the bloody events that led to the expulsion and displacement of the Palestinian Arab population. In textbooks, the events of May 15, 1948, make no mention of how Palestinians experienced the Nakba and instead represent Israel as a heroic David defeating the many enemies arrayed against it. Since 2011, the refusal to acknowledge the Palestinian Nakba is enshrined in Israeli law, with organizations facing fines if they commemorate the day.

In the face of a powerful Israel that seeks to wipe away remnants of Palestinian life and culture, there is an instinct to close ranks and develop a single story. Nuance and contradiction are luxuries that a people under threat cannot afford. Yet to remember the events of 1948 and to recount them, with their nuances and diversities, is a form of resistance: resistance against forgetting. The collective memory of the Nakba is made up of 750,000 stories, one for each of those who left their homes and were never able to return. Taken together, they offer a nuanced, real, and humane look at a community’s reaction to what is now widely accepted as an act of ethnic cleansing. My grandmother’s story, unique to her, is but one part of a collective memory of this trauma that must be told in all its shades of gray.

To recount the unique personal stories of those who lived through the Nakba is to commemorate the struggle and suffering of Palestinians who lost their land and lives at a time when Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived side by side on the land of historic Palestine. It is to inscribe individual fates onto the canvas of history, which the victors painted in large, ugly blocks. It is personal stories like my grandmother’s, and their ability to be passed down to future generations, that serve as a reminder that peace and coexistence are possible, so long as the memories of all are acknowledged.