Judging from the media coverage of the U.K. election campaign, the Scottish National Party is the most powerful force in British politics. Yes, the nationalists lost last September’s independence referendum, but seven months later, half the stories in the English press are about SNP policies and personnel or its postelection plans—even though no one who lives outside Scotland can vote for it. Why is a party that contests only 59 of Britain’s 650 constituencies playing such an outsize role in the lead-up to the May 7 vote?

For months now, polls have shown the major parties deadlocked, and nothing anyone has said in the campaign’s debates or interviews, or in the leaders’ rare interactions with actual voters, has changed that. With only two weeks left before Election Day, Britons have a good sense of how the various parties will fare, but it’s far from clear who the next prime minister will be.

The Scottish nationalists are getting all that press because talking about them is the Conservatives’ best hope for breaking their stalemate with Labour. Those two parties have ruled Britain for more than 90 years, but current projections show the Conservatives winning 269 seats and Labour taking 271, well short of the 326 seats needed for a parliamentary majority. (It’s possible to govern Britain without a majority, but minority governments are always tentative, since they can be toppled if they lose key votes—albeit less easily now than before 2010.)

Outside Scotland, where nationalist politicians have attracted crowds and enthusiasm usually reserved for rock bands, the national attitude to the election is somewhere between “eh” and “ugh.” Instead of attempting to win votes by appealing to Britons’ aspirations, politicians are instead pitching worst-case scenarios. Less “Vote for Us,” more “Don’t Vote for Them. Or Them.”

No party won a majority in the last general election, in 2010, so the Conservatives formed a coalition with Britain’s perennial third party, the Liberal Democrats. The Lib Dems couldn’t resist the lure of power, but their pact with the Tories forced them to break key campaign promises, and their partnership with a right-wing party (by British standards, at least—the Conservative election manifesto contains pledges on health care and social policy that would make an Elizabeth Warren Democrat swoon) alienated many progressive Liberal Democrats. Five years later the Lib Dems are projected to lose more than half of their 57 seats—if the polling predictions are correct, they wouldn’t have enough MPs to form a government with the Conservatives, even if either party wanted to.

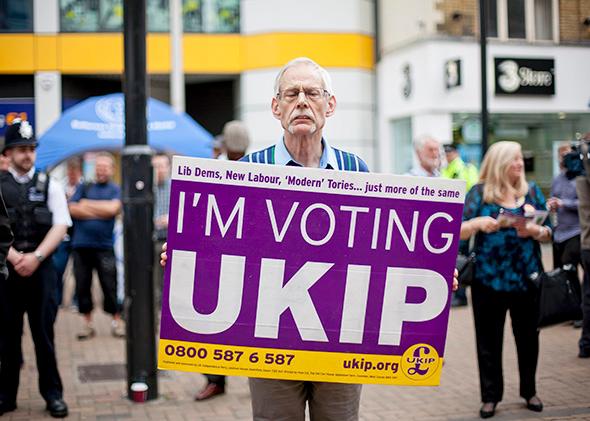

With both the Conservatives and Labour committed to austerity policies, and the Lib Dems tainted by their five-year hookup with the Tories, it’s harder than ever to argue with the view, espoused by disgruntled voters around the world, that there are no real differences between the major parties. It isn’t true, but it’s less untrue in Britain than it’s ever been before, and given this general air of dissatisfaction with the Big 3, people are pondering alternatives. Outside of regional parties—the SNP in Scotland, Plaid Cymru in Wales, and an alphabet soup of parties in Northern Ireland—voters can support the Green Party, which had one MP in the last parliament, or the UK Independence Party—a populist, anti-European Union party that had two seats in Westminster before the election but has boomed in popularity and won more votes in the 2014 European elections than any other British party.

UKIP won’t come out on top in May—indeed, it’s expected to win only a handful of seats—but the party is still serving a valuable role. Its leader, Nigel Farage, is a blokey, beer-swilling man of the people. That a former commodities trader who was privately educated could enjoy such an image is a testament to the party’s willingness to talk about issues the mainstream parties typically avoid, especially immigration. Its talking points are often xenophobic, but some sections of the British public—“older, whiter, poorer, and less educated than the UK norm”—respond to them. UKIP has benefited from a rising resentment against the political class, which has been damaged by a large-scale parliamentary expenses scandal six years ago, and turned off by the increasing professionalization of politics. Earlier this week, Norman Tebbit, who served in Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet, complained about this, saying, “There are too many people in Parliament without adequate experience of life as it is lived by most people in the country.” The amateurs selected to contest the election for UKIP demonstrate why politics has become professionalized—collecting their gaffes is a productive task for political journalists.

Given the damage serving as the junior partner in a coalition government did to the Liberal Democrats, none of the parties is interested in signing on to a formal coalition come May 8. In the next parliament, the arrangement will be more loosey-goosey, and the prospect of this kind of shadowy, few-strings-attached relationship has created a new style of scare tactics. Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg warned that unless people vote tactically (in other words, for the Liberal Democrats), they will find themselves ruled by “Blukip” (Britain’s Conservative Party is traditionally associated with the color blue), a heartless, anti-European, and—thanks to the possible inclusion of Northern Ireland’s anti-LGBTQ Democratic Unionist Party—homophobic grouping. The Conservatives, meanwhile, are pushing a slogan of their own: “Vote Nigel, Get Ed”—in other words, a vote for UKIP, rather than the Conservatives, makes it more likely that Labour, led by the uninspiring Ed Miliband, will ultimately take power. Late last year Labour was apparently muttering, “Go to bed with Nicola, wake up with Dave,” reflecting its view that if Scots voted for Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP, rather than Labour or the Liberal Democrats, David Cameron’s Conservatives would be back in power.

That was before September’s referendum, when Scotland swooned for the SNP. Even though a majority rejected independence, the nationalists’ energetic campaign apparently won over Scottish Labour voters. It now seems possible that the SNP will win as many as 50 of Scotland’s 59 seats, most from Labour. Ironically, perhaps, that means the likeliest alliance in Westminster is between Labour and the SNP. Together, according to the Guardian, they would “have the numbers to win a confidence vote.”

That partnership, however loosely constituted, might well appeal to many left-leaning voters who are frustrated with Labour’s embrace of austerity. But Cameron is hoping that the prospect will have the opposite effect. Scotland is a wasteland for the Tories, so they have nothing to lose there. By painting the SNP as extremists who are determined to destroy the United Kingdom, the Tories want to persuade unionists and centrists to vote Conservative to avoid a Labour government that would be propped up and perhaps pushed further to the left by the SNP. The Conservatives’ tactic is almost certainly doomed, but you can’t blame them for trying. Nor can you blame British voters for being frustrated by their lack of appealing options.