As hard as I try to move beyond Iraq, the country still sucks me back. Last June, I tried to cut off completely, heading off on horse back into the mountains of Kyrgyzstan. At one of the shepherds’ lodgings, I was surprised to find access to Wi-Fi. I connected my iPad to download my email and there in my inbox was an email from a U.S. general and a number of media requests for interviews. Mosul had been overrun by ISIS.

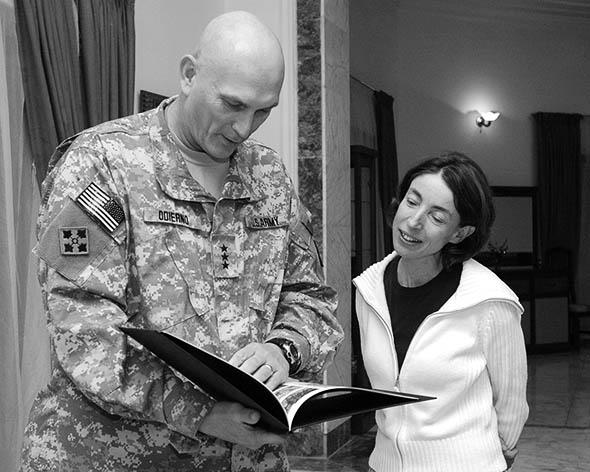

I could not stay away. I had to go back to see for myself what was happening. I had first gone to Iraq in 2003, when I responded to the British government’s request for volunteers to help rebuild the country after the fall of the regime and found myself responsible for Kirkuk, trying to diffuse tensions between the different Iraqis scrambling to control the province. During the surge and the drawdown of U.S. forces, I had served as the political adviser to Gen. Ray Odierno. I left with him in September 2010 but had been back to the country a couple of times every year since, unable to let go, unable to stop caring.

* * *

I flew to Erbil and checked in at the Rotana Hotel. It was packed with Iraqis. I observed politicians sitting together in small huddles late into the night, lamenting how Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was destroying the country and how the Iranians controlled the government. Many were familiar faces, and wanted to talk to me about the current situation and to introduce me to spokesmen of insurgent groups.

“This is a popular uprising,” a man with a big, black, Baathist moustache declared to me. He explained how the Sunnis had protested peacefully for a year, demanding an end to discrimination and the release of detainees. “But the government refused to listen to our demands and responded with violence against the peaceful demonstrators—first in Hawija, then in Falluja. We had no choice. We were forced to take up arms against the government.”

The others sat around nodding, looking at the man from Salah al-Din province with respect. “Maliki wants to carry out genocide against the Sunnis,” he claimed. “He calls all Sunnis terrorists.”

The conflict in Syria seemed to be re-enforcing sectarian narratives in Iraq. I asked him about ISIS, or the so-called Islamic State or Da’ash, as it was called in Arabic, the successor to al-Qaida in Iraq, which had taken control of one-third of the country. “Da’ash is only around 8 percent of the insurgency,” he said, as if quoting some scientific research. “But they have a big media image. For now, we allow them to be out at the front. We don’t want to show our faces.” He went on: “We will fight alongside Da’ash until we have overthrown Maliki—and then we will get rid of Da’ash.”

I told them they were deluding themselves if they thought they could use the fanatical Islamic State against Maliki and then defeat it afterward. The Baathists were fighting for power within Iraq whereas the Islamic State disputed the very legitimacy of Iraq as a state. Had they not seen what had happened in Syria? Among the Syrian rebels, it was the most extreme salafi groups that had attracted funding and recruits and were wiping out others.

“Iraqis,” I responded, “are good at coming together against someone they don’t like. The ‘moustaches’ and the ‘beards’ have come together against Maliki,” I noted, referring to the Baathists and the Islamists. “But what is your vision for the future, once Maliki is gone? What is the vision that you have for Iraq?”

The Baathist could not answer. The man next to him interrupted with complaints about the Iranians and the Shia militia. I looked around at the group, but no one could articulate a strategy for creating a better future. I made my excuses and withdrew.

* * *

The Iraqi security forces had quickly disintegrated in June in Mosul in the face of the advance of the Islamic State. Although they far outnumbered the ISIS fighters and had been better equipped, they were poorly led. There was no official chain of command through the Ministry of Defense. Instead, Maliki and his Office of the Commander-in-Chief gave instructions by phone and text. Maliki had replaced competent officers with people loyal to him. Corruption was rife. Some had taken the funds meant to buy food for their soldiers. None gave orders to their forces to fight. The Islamic State had taken possession of all the equipment that the United States had supplied the Iraqi army.

Photo by Staff Sgt. Curt Cashour/U.S. Army

Faced with the advance of the Islamic State and the collapse of the Iraqi army, Ayatollah Sistani had called on Iraqis to join the security forces to defend the state. The last time the Shia establishment had issued such a call to arms was a century ago against the British. Shia militias used the announcement as an opportunity to remobilize. Already the Iranian Gen. Qasim Suleimani was in Iraq personally directing operations, providing support to Shia militias, and embedding Iranian military advisers with the Iraqi army. Fearful of the consequences, Sistani spoke out asserting, “Sunnis are ourselves, not just our brothers.”

* * *

One evening, I met with Rafi Issawi, the former deputy prime minister and minister of finance. As ever, he was well dressed in a dark suit and tie. He told me that all his family was now living outside Iraq, divided between Jordan and the Gulf. Having lived his whole life in Iraq, he was now an exile. I could tell how much that hurt him.

So much had happened to Rafi since I had last seen him in Baghdad in January 2012, when a tank had been parked outside his house with the turret pointing at it. Toward the end of that year, days after President Talabani had been incapacitated by a stroke, Maliki had again accused Rafi of terrorism, arresting his bodyguards using exactly the same strategy he had deployed a year earlier against the vice president. It was the trumped-up charges against Rafi that had sparked the widespread Sunni protests. One Sunni had said to me: “Issawi is the best of the Sunnis. If Maliki regards him as a terrorist, then there is no hope for the rest of us.” Rafi had been forced to resign as minister of finance and leave Baghdad. It was only thanks to the protection of the tribes in Anbar that he had escaped arrest by the Special Forces Maliki had sent to detain him.

“Was it inevitable that Iraq would disintegrate?” I asked Rafi. No, it was not, he assured me. Iraq had been moving in a positive direction after the surge. This downward trajectory began in 2010 when the United States had not upheld the right of Iraqiya to have first chance at trying to form the government after it won the elections. “We might not have succeeded,” he admitted, “but the process itself would have been important in building trust in Iraq’s young institutions.”

Bad decisions taken by Americans in 2010 destroyed the country, he believed. Since then, Obama had regularly cited ending the war in Iraq as one of his greatest foreign policy successes. On Nov. 1, 2013, with Maliki by his side in the White House, Obama stated: “We honor the lives that were lost, both American and Iraqi, to bring about a functioning democracy in a country that previously had been ruled by a vicious dictator. And we appreciate Prime Minister Maliki’s commitment to honoring that sacrifice by ensuring a strong, prosperous, inclusive and democratic Iraq.” He appeared to be paying scant attention to Maliki’s growing authoritarianism and the deteriorating situation in the country.

Rafi listed the Sunni grievances that had simmered until they had finally boiled over. Maliki had detained thousands of Sunnis without trial, pushed leading Sunnis out of the political process by accusing them of terrorism, and reneged on payments and pledges to the Awakening members who had bravely fought al-Qaida in Iraq—its leaders were dead, fled, or in jail. The request by provincial councils in Salah al-Din, Diyala, and Mosul to hold a vote on the formation of regions—in accordance with the Constitution—was prevented by force. Peaceful, yearlong Sunni protests demanding an end to discrimination were met by violence, with dozens of unarmed protesters killed by Iraqi security forces. Maliki had completely subverted the judiciary to his will, so that Sunnis felt unable to achieve any form of justice.

Photo by Staff Sgt. Curt Cashour/U.S. Army

The Islamic State, Rafi explained to me, was able to take advantage of this situation, publicly claiming to be the defenders of the Sunnis against the Iranian-backed government of Maliki. In previous years, the Sunni tribes, supported by the U.S. military, had contained and defeated al-Qaida in Iraq, the forerunner of the Islamic State. Today, those same tribes were cooperating with the Islamic State in a popular uprising against the central government. Despite its perverted interpretation of Islam, they viewed the Islamic State as the lesser of two evils when compared with Maliki.

We continued our discussion the next evening when Rafi took me to a restaurant for iftar. The place was packed with families breaking the fast. We walked toward our table and all heads turned to look at him, the celebrity on the premises. He returned the greetings. Most of these people, he explained to me, were Arabs from Anbar. President Barzani had shown great compassion, providing refuge to many fleeing the violence.

“You worked so hard,” he reassured me, like a big brother. Over my years in Iraq, I had seen where and how we could be effective in nudging people closer to each other, in mediating between factions and in brokering deals. I had learned that violence was an extension of politics, that hatreds in this land were new not ancient, that alliances could be forged and fractured, and that friendships counted for more than flags.

Rafi to me embodied the potential of Iraq for a better future, the hope for pragmatism to defeat extremism. But sadly the Salafism of the Islamic State was displacing the Sufism of Rafi. The once interwoven rich tapestry of Iraqi society was unraveling as groups became increasingly segregated and sectarian identity more prominent.

The Iraq war—and the way in which the United States departed—tilted the regional balance of power in Iran’s favor. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and other states in the region all sought to project their influence by supporting sectarian actors in different countries—with devastating consequences.

When spring break came last month, I was once more drawn back to the region. A number of Iraqi friends had had their houses destroyed and relocated to Jordan. I asked one sheikh which tribes were standing up against ISIS. It was difficult, he told me, as Sunnis were not provided with support. “Why isn’t America helping us?” he asked. It was the Shia militia and the Kurdish peshmerga that were doing most of the fighting. I asked after Sheikh Lawrence, who a few years ago had put together a large awakening to protect his area from al-Qaida. “You didn’t hear?” the sheikh responded. “They killed him two months ago.”

I explained to the sheikh that last summer I had visited northern Iraq and met men with large Baathist moustaches who claimed to be spokesmen for insurgent groups and said they were leading a large Sunni uprising and would turn against the Islamic State. What happened to them, I asked. The sheikh responded that they had never shown their flags, that it had all been talk. Some had grown beards and joined the Islamic State. Others had sat on their hands doing nothing. Others had been executed. The Islamic State had quickly dominated the Sunni areas, ruling with an iron fist.

* * *

Nothing that happened in Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003 was preordained. There were different potential futures for the country.

The Iraq war and its outcome affected few Americans. There is little willingness to reflect on or take responsibility for what happened there. Politicians try to use the situation in Iraq for political advantage, without much consideration of actual Iraqis; Democrats blame Republicans for invading Iraq in the first place and Republicans blame Democrats for not leaving troops there.

But what happened in Iraq matters terribly to Iraqis who hoped so much for a better future—and to those of us who served there year after year. If we refuse to honestly examine what took place there, we will miss the opportunity to better understand when and how to respond to the world’s instability.