BUDAPEST, Hungary—In the United States, nobody listens to Jared Taylor. Despite his Ivy League education and polite manners, few people working in politics take him seriously. That’s because he is a white supremacist, although he would prefer to be called a “racial realist.” When he tries to organize a meeting for his publication, American Renaissance, it is typically banned from hotels and conference rooms as soon as the proprietors find out about its racist mission. His ideas obviously hold little sway with established political parties or institutions. Which explains why Taylor traveled to Hungary last month to organize an international conference of white supremacists and anti-immigrant nationalists from more than 10 countries with the express purpose of making common cause with Europe’s own burgeoning far-right political movements. The conference was blandly dubbed “The Future of Europe.”

Taylor and his fellow organizers, the Montana-based white nationalist think tank National Policy Institute, chose Hungary because of the rise of far-right nationalists in that country; they thought it might offer a hospitable environment for their assembly. In fact, it was the opposite. The Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán—a member of the leading conservative party who has been criticized for his increasingly authoritarian politics—banned the conference. While Orbán has support from Hungary’s far-right parties, he likely saw this move as an easy way to help position himself as a moderate conservative in the runup to local elections last month. Orbán even ordered police to arrest anyone trying to organize the event. William Regnery, the founder of the National Policy Institute (and heir to the conservative publishing powerhouse Regnery, home to best-sellers from Ann Coulter, Dinesh D’Souza, and Edward Klein, among others) was immediately sent back to the United States when he arrived at Budapest’s airport. Richard Spencer, the director of NPI, was arrested in a Budapest pub when he tried to organize a casual gathering of the conference’s attendees. The conference-goers already had been evicted from the hotel where their meeting was scheduled to take place.

Spencer spent the next three days in a Budapest jail, which he didn’t seem to mind. He kept emailing fellow attendees and journalists from his prison cell. When I met Taylor in Budapest, he compared Spencer’s Budapest emails to Martin Luther King’s “Letter From a Birmingham jail.”

Most of the media coverage of the conference centered on Spencer’s arrest. But, even if it was foiled and ill conceived, the entire episode represented something else: It was the first attempt by NPI and American Renaissance to establish a presence in Europe, in an effort to establish a kind of Euro-American partnership for white nationalism, or “Eurocentrism.”

Taylor, Spencer, and the other Americans visiting Budapest see their cause as an uphill battle. The race-industrial complex in America just isn’t what it used to be. By crossing the Atlantic and trying to organize Europe’s disparate far-right groups into a unified movement, they are trying to breathe new life into their own cause. It is an ambitious undertaking coming from two tiny, fringe organizations. The National Policy Institute is based in Whitefish, Montana, and has four employees. Taylor’s American Renaissance, based in the D.C. suburb of Oakton, Virginia, is really just a one-man show.

With Spencer in jail, Taylor became the host of the conference. Despite the fact that the government had forbidden the gathering and informed all attendees that they might be arrested if they went ahead with their plans, 70 of the 135 registered attendees showed up in Budapest, including a Mexican man who claimed to have traveled “10,000 miles.” Others traveled from Britain, Norway, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Spain, Hungary, and Japan, as well as a dozen from the United States. What did they all have in common? “The conviction that Europe is in a life-or-death struggle. Europe can’t remain Europe without Europeans. When we are being replaced by non-Europeans, it threatens our core way of life,” Taylor said.

We were standing in a hotel lobby close to the Buda part of the city, on the western side of the Danube River. Taylor was looking around the lobby anxiously, aware that he might be arrested at any moment. Every man walking by could, in his mind, be a plainclothes Hungarian police officer. But overall Taylor was upbeat. He was happy to be in Europe, where he said things are going in the right direction, referring to the recent voter backlash against immigrants and multiculturalism. “Europeans, like Americans, see their world changing. They never asked for this change. Their neighborhoods are becoming different, and they don’t recognize it anymore. So they are reacting against this,” Taylor said.

In the May elections for the European Parliament, Europe’s far-right parties made extraordinary gains. France’s National Front and Britain’s U.K. Independence Party won 24 seats each in the EU Parliament. UKIP’s win marked the first time in a century that the Labour or Conservative party didn’t become the biggest party in a national election. In Hungary, the extreme-right party Jobbik—best known for its calls for Hungary’s government to register and monitor all Jewish residents—won a third of the country’s youth vote, and nearly 15 percent of the total vote. Overall, the elections showed an incredible rise in support for parties defined by their tough stance on immigration and a general “Euroskepticism”—a scornful pessimism for the entire EU project.

Nevertheless, nationalist groups don’t represent a plurality of the population in any European country. Rather, they are an outspoken white minority who are anxious about their increasing marginalization, which gives them a reason to organize. Their alienation from mainstream society also makes them feel more closely allied to each other. As xenophobic ideas are increasingly frowned upon, Europe’s far right feels as though they are the ones being discriminated against. They see themselves as rebels fighting a corrupt system that has turned against them. Spencer’s arrest, of course, only confirmed this belief. On the websites and Internet chat rooms of Europe’s nationalist groups, Spencer instantly became a martyr and a hero. His arrest may have inadvertently done more to help the American white supremacists connect with Europe’s far-right groups than anything else.

Far-right parties like Jobbik in Hungary, the National Front in France, and the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn in Greece can no longer be brushed off as irrelevant. They have become a genuine political force in Europe, with voting power in a string of governments. And now the American nationalists want to know how they can join the party. “It’s very difficult to run as a candidate, and not be either a Republican or a Democrat. So in that respect, I think, democracy is far more restricted in the U.S. than in many European countries. I’m convinced that if people who hold my views were part of a proportionally representative system, that we would have 15 percent, 20 percent, maybe 30 percent of the vote,” says Taylor.

So how does Taylor plan to change this? “That’s a good question. I think it might be possible to run as a Republican under certain circumstances, but we are really very far behind our European comrades on this. They’ve been much more successful at expressing themselves politically.” Taylor pointed to several congressional Republicans—Reps. Joe Wilson, Steve King, Louie Gohmert, and Dana Rohrabacher, among them—whose anti-immigrant rhetoric has at times mirrored that of far-right parties in Europe.

In Budapest, I also spoke with Kevin DeAnna, a young conservative activist from Washington, D.C. DeAnna was staying in a cheap hostel with Spencer, since they had both been thrown out of the swankier hotel where they had planned to stay. DeAnna joined Taylor as a sort of last-minute organizer of the conference, or what was left of it. He met the attendees in a dingy subway station, wearing baggy jeans, sneakers, and a blazer and tie. “We’re kind of running this underground as a guerrilla movement now,” DeAnna said when he arrived to the subway station, where the conference attendees had been told to gather, awaiting further instructions.

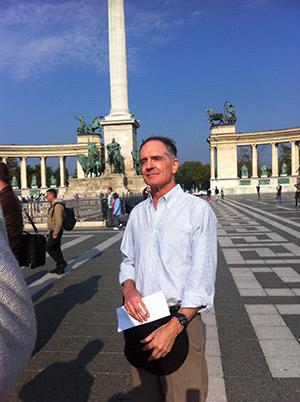

Despite the intervention by Hungarian authorities, the conference did go on as planned, even though Taylor insisted on calling it a dîner-débat, rather than a conference, to avoid possible legal repercussions. The day after the meeting, Taylor and his fellow attendees stood in the sunshine in Heroes’ Square, discussing whether they would visit the House of Terror museum, where the violence of communism is documented, or the Museum of Ethnography. He was pleased with the event. Europe gets it, he said. And America? “The left is constantly describing us as either insane, or evil, or ignorant, or all three. That’s simply not the case. They are, frankly, terrified that people who hold positions like mine or Richard Spencer’s will have an opportunity to speak openly and publicly. If Americans had an opportunity to vote for my views, I believe many of them would. But the political system is not set up in a way that makes that possible or practical.”