During the Cultural Revolution, a million people were killed or driven to suicide, many for infractions as incidental as making a “politically incorrect” comment or having the wrong family tree. It was a personality cult, a reign of terror, and a witch hunt all at once. For 10 dark years until his death in 1976, Mao eradicated any perceived threats, from foreign ideas to native traditions to his own oldest, closest comrades.

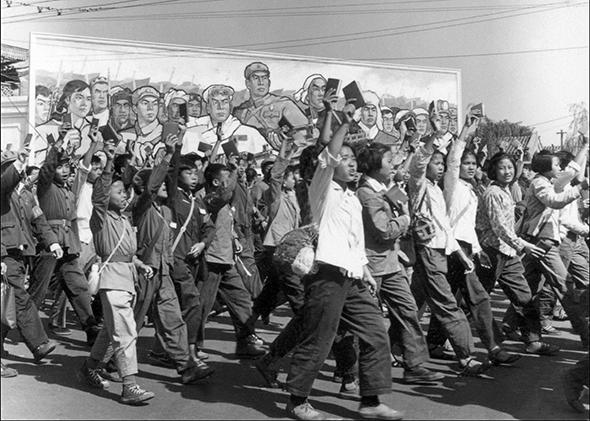

To do so, Mao unleashed the youth—the infamous Red Guards—on Chinese society, espousing a radical philosophy rooted in violence and paranoia. The result was mayhem. Factory production stopped. Schools closed. Farms ground to a halt. People were tortured and driven to suicide in public “struggle sessions.” The Red Guards were Mao’s footsoldiers, teenagers and college students designated to mete out punishment. The death toll exceeded 1 million, although the precise figure is impossible to know. The enemy was said to be “the Four Olds”: old customs, culture, habits, and ideas. But Mao’s real goal was to purge any people or values that threatened his continued rule.

In May of last year, I traveled 75 miles east of Beijing to Yutian, a county known best for its cultivation of long, crisp cabbage. Specifically, I made the trip to attend the 46th-year class reunion of Yutian First, the local high school. Technically, the class of 1967 never graduated—the school was shuttered at the time. It is still in the same place, but only the original campus gate remains, with the rest redone in white-tiled buildings. I went looking for truth and reconciliation: Had the victims healed? Had the perpetrators apologized? How had the class of 1967—a group of young people who came of age just as the Cultural Revolution was approaching its height—come to grips with their own role in this dark chapter in modern Chinese history?

The level of mayhem during those days varied greatly across China. In the most violent cities, such as Chongqing, high school factions battled each other with heavy artillery in the streets. I expected softer stories in Yutian. I sat down with two dozen former classmates at an old restaurant, under mustard wallpaper with a framed hologram of Mao. If you leaned from side to side, Mao also leaned back and forth with you, but from high above Tiananmen Square, pontificating and reading from his own Little Red Book.

Between spins of a lazy Susan, a soft-spoken man recalls how he was banned from any job but farming because his father had run the granary during the Japanese occupation. My next question: “When did you start to doubt Mao?” He hesitates, “Well, maybe after he died,” he says, as he’s quickly interrupted by a stockier fellow sitting next to him: “I have never doubted Mao,” says Zhu Zhanjun. “Whoever doubts Mao is not a Chinese person.”

It’s hard to overestimate the nostaglic pull of those days for these former Red Guards, even nearly five decades later and despite the pain they endured. When I ask 68-year-old Zheng Suxia, a gentle-looking lady with long gray hair tied back in a bun, “What’s your worst memory of the Cultural Revolution,” she actually smiles and waxes on about the good times. Maybe she misheard my question.

Either way, she and Zhu still speak of Mao in reverential terms. Seeing Mao in a crammed Tiananmen Square, he says, “We didn’t even have to walk. We were just carried along by the crowd. You would lose your shoes unless you tied them on with string.” Zhu reminisces about these days, despite the fact that a few years after he saw Mao speak in Tiananmen, Red Guards beat his father to the point of permanent nerve damage. For Zhu, it was a test of his revolutionary faith, and he passed.

To be fair, their nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution isn’t entirely inexplicable: It was their youth and it was the first time they could escape from hardscrabble Yutian County, where almost everyone had known someone who died of hunger less than a decade earlier. According to government figures uncovered by Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng for his searing book Tombstone, 410,000 people starved to death in the surrounding province during the Great Leap Forward, which was directed by Mao but is still—when discussion is allowed at all—blamed on drought, the Soviet Union, or the incompetence of local officials. Under Mao, peasants were treated as slave labor, unable to travel beyond their hometowns, especially during the famine. By comparison, the early years of the Cultural Revolution were akin to the luxury junket of a lifetime. Mao encouraged the young people to take trains to “spread revolution.” Wherever they went, they were boarded and fed more than they could eat. Zhu and his friends spent months on the rails. “All we needed to carry was a meal card.” Few if any of them have traveled as far since.

Not until they returned to Yutian did the genuine burden of revolution fall on their shoulders. The class of 50 students had to choose one “counterrevolutionary.” All along, Mao imposed quota systems of enemies to be found and persecuted, in order to terrorize people into conformity and submission. For example, in the early 1950s, the “killing quotas” (the regime’s own term) called for one execution per 1,000 in the countryside, twice that in the cities, and far more at universities. A few benevolent leaders supposedly nominated themselves. More often, victims were determined by grudges, envy, or personal disputes. The quota system brought out bloodlust, paranoia, and the most brutal group instincts. In the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards were given lists of houses to ransack, but also quotas for “counterrevolutionaries” to choose from among their own.

“Every class had to find one. Some found a teacher who was the child of landlords. Some classes found students. We picked Wang Qichuan,” says Wang Yiping, one of the classmates. Directing the movement were soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army stationed at their school. “They said, ‘You have to find a counterrevolutionary. If you don’t, you’re disrespecting Mao. You just have to.’ It fell on his head.”

His fellow classmates can’t explain exactly why they picked him. “He complained and grumbled more than others,” says Wang Yiping. Classmates drew up posters condemning him, black letters on white paper. Soon after, he swallowed mothballs in the dorm—the only poison they had around then—and was taken to the hospital to have his stomach pumped. “I don’t remember why he took the poison,” says Zhu. “He didn’t have enough courage.”

Wang Qichuan didn’t attend the class reunion. But he was rumored to be making a fortune in the recycling industry. I pictured a local trash kingpin, overseeing a business so lucrative that he didn’t want to retire, as his peers already had. Wang Yiping suggested it wasn’t worth contacting him to dredge up the past, but I found his name and phone number on a school roster and slipped outside the restaurant to call. When I reached him, Wang Qichuan seemed willing to talk. “Take the bus out to the sheriff’s station,” he told me. “Get out and walk all the way around it. I’ll be here.”

Most literary narratives of the Cultural Revolution are told by young urban intellectuals banished to the countryside after Mao decided they’d wreaked enough havoc in the cities. But for this class of 1967, the countryside was where they came from; they were the lucky few to make it into high school in the county seat, where the college entrance exam awaiting them was their only hope of not being sent back. But the entrance exam was canceled nationwide in 1966, and they were all sent home. Wang Yiping would spend years paying back school loans to neighbors—money he had borrowed to pay for high school. For the next decade, only officials’ relatives got into college.

The oft-repeated story is that when the Red Guards were “sent down,” the cities cooled off and the worst was over. But in the countryside, for these youths who were “sent back,” it was just getting started.

Wang Yiping’s older brother was a decorated veteran from the Chinese civil war that ended with the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. He walked with a limp, which had saved his life when he was proselytizing in areas controlled by the Kuomintang. (Two of his comrades had been walking faster up ahead. After seeing them felled by a sniper, he had time to hide in the fields.) But being a lone survivor always attracted suspicion. In 1969, his neighbors borrowed his radio and accused him of tuning into foreign stations. He was locked in a local jail for two years, until he hung himself. “My mother was so angry; he had been her smartest child,” says Wang Yiping. She could not express anger toward those who had driven him to suicide for fear of retribution. Instead, she slapped his corpse, saying, “ ‘Don’t you know—this is exactly what they wanted you to do.’ ”

Even now, few people have any opportunity to vent their anger. President Xi Jinping, in a classified letter to universities last year that leaked to the Chronicle of Higher Education, reaffirmed that despite the fact that more than three decades have passed, earlier mistakes of the Communist Party are still off-limits. They’re one of seven “unmentionables,” including universal values, press freedom, judicial independence, and civil rights. Intellectuals were hoping this newer, younger leadership might distance itself from Mao; that would be the truest sign of reform. They remain disappointed. In the meantime, Mao gets millions of faithful visitors every year, pilgrims from the countryside laying flowers at his tomb. And when I ask gentle old Zheng Suxia, one of the Yutian graduates, “Why is Mao the greatest?” she points to his mausoleum as official evidence. A lot more people don’t know whether the Cultural Revolution was a good or bad movement. They just care whether it was good for them.

That afternoon, I took the bus out to the sheriff’s station and found Wang Qichuan about 100 meters behind it, in his junkyard. He lives in an airy shack cluttered with broken things. He is no recycling magnate; he makes less than $5,000 a year. He is noticeably taller than his classmates, and also much quieter. “I’ve never talked about the Cultural Revolution with my children or my wife,” he says. “It was a catastrophe—there’s no way to talk about it with them.”

On one wall is a photo of his grandson, the first to make it out of Yutian; he studies sports at a university near China’s Siberian border. There’s another photo of a young man with sensitive eyes—that’s Wang Qichuan’s father, who died when Wang was 6, right before his grandfather “lost his mind” and stopped working altogether, leaving Wang to support his two sisters by selling bean cakes on weekends.

And that explains why he was chosen to fulfill Mao’s quota: He had no time to make friends and allies in his class. Even though he reaped the whirlwind of the Cultural Revolution, he still knows very little about it. Even now, he hadn’t heard of Mao’s counterrevolutionary quotas. He assumed he was singled out because he wasn’t popular. For practical reasons, he has long since repressed any sense of injustice; he even joined the Communist Party. So he just says, “I would never doubt Mao,” and then eerily repeats the propaganda mantra from a song: “If there were no Mao, there would be no new China.”