On Sunday, Israel’s weekly cabinet meeting ended in a brawl. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, backed by the attorney general, decided to postpone a vote on legislation he committed himself to passing. If the bill passes, Israeli courts could sentence murderers for life in a way that would prevent their future release for whatever reason. The authors of the new legislation, who are Netanyahu’s coalition partners, aim to prevent Israel from ever again releasing prisoners in exchange for peace talks, as happened in the last year when a failed attempt at achieving peace included such deal. The legislation would also prevent the government from exchanging prisoners for abducted Israeli soldiers.

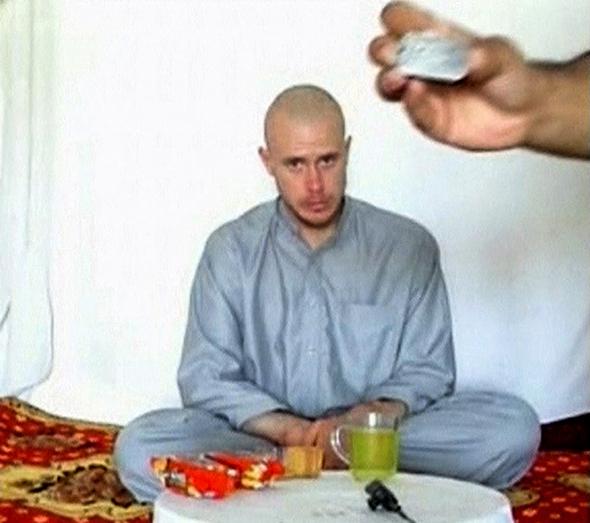

That Israel might be in need of such legislation is testimony to the slippery slope that the releasing of terrorists can become. Three years ago, Israel got an abducted soldier back from Hamas captivity in exchange for releasing 1,027 Palestinian prisoners. It was not the first time such price was paid: In 1985, Israel released 1,150 prisoners to get three soldiers back. Israel has repeatedly paid heavily for information, for bodies of dead soldiers, for a drug-dealing Israeli colonel kidnapped by Hezbollah. It got used to paying—and to bickering about it. Time and again, Israel caved under pressure, and negotiated an exchange.

It is always a two-stage pressure: First, the public is psychologically pressured by the enemy and by having to think about the victim of abduction. Then, that vulnerable public pressures the government to make the deal.

So the U.S. got a captured soldier back in exchange for five Afghan inmates. Big deal. Five-for-one is a deal Israel would take in a heartbeat. But there’s truth to the claim that such deals increase the appetite of a terrorist organization in two ways. First, they encourage terrorists to adopt a policy of an abduction of soldiers in the hope of getting more inmates out. Second, they allow terrorists to worry less about being captured by the U.S., since they can hope for a later release.

Israel had been attempting for years to try to resist these exchanges. In 2008, following a heavily criticized deal in which Israel let murderers go in exchange for body bags, then Defense Minister Ehud Barak appointed a special committee, headed by former High Court Chief Justice Meir Shamgar, to make recommendations to the Israeli government on future exchange deals. The Shamgar committee pushed to put limits on prisoner swaps, for the reasons above.

But a committee is little match for a mourning family. The public might oppose the release of terrorists on principle, but it folds easily when there is a specific soldier in danger—trading many dangerous enemies for a soldier that all Israelis care about, with a face they all recognize, with a family they all learn to identify, with a smile they all adore. Committees and wise strategists aside, Israelis put stickers on their cars and march along to Jerusalem to demand a deal. Time and again they force their governments to make an admirable yet irrational choice.

The Shamgar committee was ready to submit its report in 2011 just when Israel was finalizing the swap to release kidnapped soldier Gilad Shalit. It was decided that this one specific deal would not be impacted by the recommendations. Three more years have passed yet the cabinet still has not found the time to discuss the Shamgar report. Earlier this week, when Netanyahu postponed the vote on the prisoners’ law, and hoped to subdue criticism, the prime minister vowed to bring both the new legislation and the much older report to a cabinet meeting “possibly as early as this week”.

Susan Rice, Obama’s national security adviser, defended the administration’s decision to make the swap by invoking a “sacred obligation” to leave no soldiers behind. Only time will tell if she is serious about meeting such obligation. But clearly, the release of one makes future deals more likely. It makes future choices less coherent: Why him and not the next one? Why release five Taliban and not six or seven? Where is the line beyond which a deal is unacceptable? What is the price unbearable enough to resist?

The Shamgar committee is supposed to assist an Israeli government as it goes to a bargaining table. But committees and recommendations are all quite easy until the mother of a missing soldier begs for the country that sent him to battle to pay a price to also get him back.

The lesson from Israel for America is that given the opportunity the head always loses to the heart. Nothing compares to the smiles and the tears of a uniting family. But all decisions leave a bitter aftertaste.