“Keka, my teacher!” Pero hollered Dad’s nickname. “You look like a hawk. My brother and I were just talking about you.”

My 74-year-old father looked ecstatic to be Skyping with his old student on my laptop. He yelled back in Bosnian, “My Pero, it’s been 20 years!”

“Longer,” I said. It seemed surreal to be sitting with Dad in my one-bedroom in Astoria, video-chatting with the 54-year-old Serb who’d saved us two decades earlier.

When the Balkan war started in August 1992, I was 12 and living in Brčko, Bosnia, my Eastern European hometown. I watched from our balcony as my father and older brother, Eldin, were dragged onto a bus carting Muslim civilians to a concentration camp. My mother ran to the nearby police station, where Pero then worked. I was terrified my whole family would perish.

Pero typed up some paperwork and ordered two officers to rush my mother back home in an official car. When she gave the guards the documents, they obeyed Pero’s mandate, releasing Eldin and Dad. Then, five months later, we desperately needed Pero again. Despite being a Christian Orthodox Serb, he saved my Bosnian Muslim family from the ethnic cleansing campaign a second time. He made a call to the Bosnian-Serbian border guard so we could flee the country. We carried one small suitcase each, the remnants of our once-happy life.

Now 33, I am the age Pero was then. He’d been presiding over the notorious police station where my former karate coach—also named Pero—had smashed a fellow martial artist’s hands with a hammer and executed him in cold blood during the war. I still couldn’t believe my beloved coach, the original Pero, had come to our door with an AK-47 shouting, “You have one hour to leave or be killed!” Pero was a common Yugoslavian name, like Peter, but I only knew two. In my 12-year-old mind, they became “Bad Pero” and “Good Pero.”

Good Pero was the police chief of the Bosnian-Serb national security and crime prevention squad, ironic since his headquarters turned into a torture chamber with blood streaming down hallways. Muslims men we knew were bludgeoned to death with guns and bayonets there, women raped by former schoolmates.

It was still hard for me to make peace with the past, especially when Serbia continues to deny they started the war, it ended in stalemate due to U.S. intervention, and no official reparations were ever made. Just last February Bosnia demonstrators set fire to government buildings, protesting corruption and the 40–55 percent unemployment rate still plaguing the nation. I wondered how Good Pero felt about his fellow soldiers, who were never punished for dumping their dismembered Muslim and Catholic neighbors’ bodies into mass graves, leaving corpses littering the River Sava, the ruined playground of my childhood.

“I’m sorry about Adisa,” Good Pero said via our Skype connection. He offered condolences for my mother, who died of cancer in 2007. “How are you recovering from your aneurism?” he asked Dad.

“I didn’t know who I was in the hospital,” my father answered. “I’m better since I moved to Astoria, near my Brčko buddies.”

“There’s 10,000 former Yugo’s like us here in Queens,” I explained, updating him on Connecticut’s Interfaith Council, who’d sponsored us in the United States, getting my American citizenship and physical therapy degree, the Manhattan job I’d held for seven years that allowed me to support myself and, with Eldin, pay Dad’s rent for his nearby studio apartment. We’d sworn to Mom we’d always take care of him.

“You’re in good shape, following your Dad’s footsteps,” Good Pero said.

In wide-framed glasses, dressed in a crew neck sweatshirt, he looked like an average middle-aged Balkan man. Maybe 5-foot-7, like Dad. He sat at his dining room table in Vienna, where he’d settled after the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia.

I glanced at Dad. Since the stroke had taken his English, I’d become his lifeline. Last summer he’d insisted we visit the country that exiled us, longing to see it once before he died. He loved reuniting with old friends from back home, who sent greetings I’d read him on my Facebook page.

For me, the trip ignited a darker obsession. While there I’d checked off the list of former friends I’d confronted who’d denounced, double crossed, or stolen from us during the war. I’d since become preoccupied with tracking down those who’d rescued us. I’d been Googling Yugoslavian names, hoping to find Good Pero. But my motives were more complex than Dad’s nostalgia. I had something important to tell him.

“How did you meet my father again?” I asked him, not letting him see me taking notes on the side.

“Me and Vojo took Keka’s phys-ed class. My brother says if it wasn’t for Keka, he wouldn’t be a professional athlete now in charge of the Austrian-Judo Federation.”

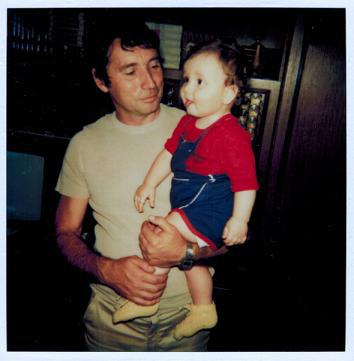

Photo courtesy of Kenan Trebinčević

Dad smiled. I relished hearing of his glory days as an athletic trainer, owner of the only fitness center in Northeast Bosnia. This was before we became nobodies, exiled, penniless in Connecticut, where Dad slung poultry at Boston Chicken, bagged groceries, and painted houses to avoid welfare. Before Mom’s cancer spread, and the stroke forced him to retire. Growing up, Dad was the unofficial mayor of Brčko; everyone treated me well because I was his son.

“Thank you for what you did,” I told Good Pero.

“It was hard to be brave at that police station,” Good Pero admitted. “In that disastrous chaos, I chose to have a conscience, to help Keka. Because of what he did for my brother and me. We remember your father and the winners he created.”

Dad nodded, quiet as usual, pleased not to be forgotten. He was somebody again. But I had something to confess. My voice quivered as I told Pero of my memoir about returning to Bosnia 20 years after the war, to face those who’d turned on my family. “Before you hear about my book from anyone else, I want to tell you. I revealed what you did for us.”

I feared he’d be angry that I’d outed him for aiding a Muslim family. My hands were clammy.

“Anything for Keka,” he said.

I was relieved, yet unsatisfied. How many Muslim murders did he witness? I’d never let go of my grudge against my former countrymen. For once I wanted to hear a Serb apologize for the massacres that ultimately left 300,000 dead.

“My karate coach Pero barged into our home with a gun and screamed at us to leave,” I pushed. “He sent Dad and Eldin to the concentration camp.” This was not over for me.

His eyes lowered. I pictured him 20 years ago: a lawyer who’d become police captain, powerful in blue camouflage, with thick black hair, armed, in a cushioned recliner behind a desk decorated with handguns and rifles. Today he was older, grayer, smaller, with no uniform or weapons. At 6 feet and muscular, I’d become stronger than he was. He stopped making eye contact with the Web cam. His slim frame shriveled, as if I was shoving an old horror film in his face that he hated to replay.

“I know everything you went through,” he cut me off. “I know the story of the checkpoints where you were stopped and thrown off buses, how you were betrayed by your karate coach Pero.” He shook his head. “I remember getting the call from the Serbian-Bosnian border and being screamed at.” He sighed, sounding distressed, like he’d just gotten off the phone with the border patrol who wanted to shoot us. “It’s something that will stay with you forever. You can’t ever erase the memory. Thoughts will come and go like weather patterns, briefly throw you.”

He’d switched to second person. Was he deflecting blame by throwing us all together, as if victim and perpetrator were the same?

His voice turned heavier, holding our shared loss. It was night in Vienna; he looked exhausted. At 1 p.m. Saturday in Queens, I was wide awake, our conversation reactivating past rage. Good Pero was not persecuted and exiled from his country. He was safe at his police headquarters, in the town Serbs occupied after they became the overnight majority. How badly had he really suffered?

“When did you get to Vienna?” I asked.

He’d snuck to Austria in 1995, in the middle of the conflict. Did that mean he was a deserter? I was impressed. Maybe seeing the senseless brutality against Muslims took a toll on Good Pero, so he’d made a moralistc statement by leaving.

“When I arrived in Vienna and tasted peace, that’s when panic knocked on my door,” he said. “At night, I’d stare at the ceiling, anxiety ripping through my skin. Away from the war, when my brain stopped fearing for my life, I stopped sleeping. Only then did it hit me what was lost. Nothing normal remained.” His voice was somber. “The first four months in Vienna, where there was endless food, running water, and electricity, I barely closed my eyes at night. It took me 10 years to sleep well.”

I was moved. I’d lost my innocence, my childhood, watched my parents’ lives ruined. Yet I never had post-traumatic stress. I could sleep.

Photo courtesy of Kenan Trebinčević

Prior to the war, I recalled that Pero had dated a Muslim girl who’d escaped the carnage. He said that they’d reconnected in Vienna, where they’d married. Now I could hear her soft voice echo from their living room walls as she greeted Dad and me. Was that why he was so compassionate to my late mother?

“Next time you go to Brčko, pass through Vienna and stay with us,” he offered.

“Definitely, we have to,” my father answered.

I realized that Pero never had the power to stop the massacres. Yet he’d carry our murdered citizens on his conscience. I could never forget: He saved my family. I decided he was a noble man trapped in a depravity he didn’t ask for. While I was a bilingual world traveler nearly able to move on, history held him hostage, keeping him from rest. I wondered for the first time if he’d suffered more than I did.

“Thank you,” I repeated.

I logged off. “How about that?” I asked Dad, feeling dazed and older.

“Incredible,” he replied, giving me a high-five, then hugging me. “Great that you told him.” Then, in English, he said, “Thank you,” beaming at me like I’d just become his hero.