Dave was in his office at the university when he got the call.

“There’s a plane leaving Shiraz in three hours.” The voice on the other end was Dave’s friend Martin. “There are two spare seats.”

The airport had been closed for more than a week, but somehow a British construction company had convinced the authorities to open it for a charter flight to pull the last of its employees out. Their wives and children had been evacuated weeks ago. Martin, an internist at a Christian hospital, had treated some of the company’s employees and they tipped him off about the flight and the spare seats. Martin’s wife and daughters would be taking five of them. Dave and Lynne, he said, could have two.

Dave biked home through deserted streets, soldiers watching him from tanks as he rushed through the intersections. He burst in the door and told Lynne that they had one hour to pack. They scrambled, valuables first—cash, Bibles, clothes—then ran out the door with one suitcase each.

The bus to the airport took 30 minutes. As they passed a gas station, Dave saw a man being pulled from his car by soldiers and struck in the face with a rifle butt. The bus turned before he could see whether it was a foreigner or an Iranian.

The airport terminal was closed, so they ran around the building, across the tarmac, and onto the plane. They got on, sat down, looked at each other. Martin’s wife and four daughters were there, buckled in, but Martin had stayed behind. The flight would take them to Bahrain, drop them off, and then come back for another batch of employees.

The doors closed and the engines started up. The plane taxied, accelerated, took off. As soon as the wheels left the ground, the passengers erupted in cheers and applause. When the plane leveled off, the flight attendants opened Champagne.

The date was Jan. 3, 1979. Dave and Lynne had moved to Iran to be Christian missionaries, but it had become gradually, then suddenly, clear that they had chosen the wrong country, the wrong time, the wrong reason to be there. Soon, the country spiraling and shrinking below them would be an Islamic Republic, the Shah going into exile, the Ayatollah Khomeini coming out of it.

“Welcome on board.” Dave looked up to see a flight attendant looking down. “So would you like to buy a ticket for this flight?”

* * *

Dave and Lynne are my parents. I’ve been hearing this story for years, how they moved to Iran with no idea the revolution was coming, how they got out right before it began. This “one hour, one suitcase” dash to the airport is family lore, a story we tell over and over.

Last year my parents unearthed a box with all of their letters from Iran, June to December 1978. They describe the city, the culture, the politics, their jobs, their friends. They do not describe a country crumbling around them, a revolution obvious and inevitable. In fact, much like my parents’ letters now, they are mostly about the weather.

Starting last fall I sat my parents down for a proper conversation about what happened. I read their letters, made them repeat the timeline, interviewed their friends who were there in ’78. And I kept asking the same questions: How could you not see the revolution coming? Why didn’t you leave sooner? And what were you doing being Christian missionaries in Iran in the first place?

The third question, it turns out, is the easiest to answer.

Dave got the idea in 1975. At a conference for Christian students, he met a woman who had just returned from a stint as a “tentmaker” missionary overseas. The idea was named for the Apostle Paul, who supported himself making tents while spreading the Gospel. Tentmaker missionaries moved to non-Christian countries and took day jobs in their professional fields, then did some light missionary work in their spare time.

This sounds dastardly, like some sort of Salvation Army covert ops, but the idea wasn’t standing on street corners with a picket signs or handing out Bibles. The objective, as the woman at the conference put it, was just to “witness”—set a good example, answer questions, be an ambassador for Christianity in countries where most people didn’t know one.

Dave had met Lynne a year before the conference, at another social event for young Christians. Just after the conference, they started dating, and Dave pitched Lynne the idea of spending their first few years of marriage doing this tentmaker thing. Dave was from rural Ohio. His only experience of the world was two years on the USS Enterprise, parked off the coast of Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. Dave was one of the aircraft carrier’s dentists, cooped up below decks, only seeing the ports for a day, a weekend, at a time.

Lynne was the daughter of an Air Force colonel, and grew up in two-year stints on military bases in Germany, Greece, all over the United States. She lived in France for a year in college, and she still reads Little House on the Prairie in French, over and over again, almost every year. For Dave, being a tentmaker missionary was a way to catch up to Lynne’s international experience, to turn his brief glimpses of other cultures into a stare. For Lynne, it was a way to start over somewhere as an adult, a return to the arrive-and-adjust cycle she remembered growing up.

In 1976 they got married, and in 1977 Dave started sending out applications to teach at dental schools in minority-Christian countries. Egypt, Hong Kong, Iran—they weren’t all that concerned about where they ended up. The point was to go somewhere different, difficult. The specifics they could figure out after they arrived.

The first response came back, a job offer, a two-year teaching gig at Pahlavi University in Shiraz. They looked up the city in an atlas: 4,000 years old, 500,000 people, 90 minutes’ flight south of Tehran. Sure, why not? They accepted the offer and started packing.

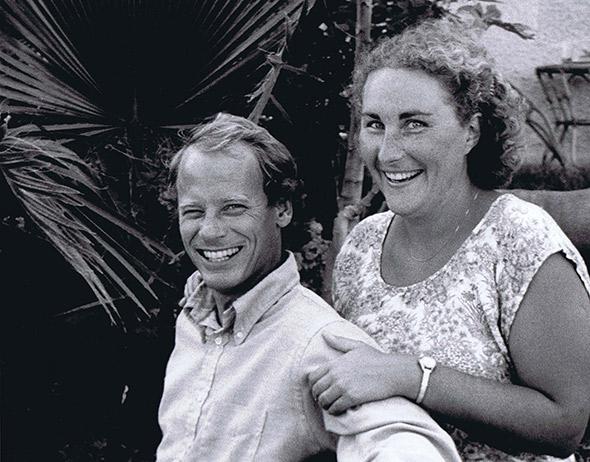

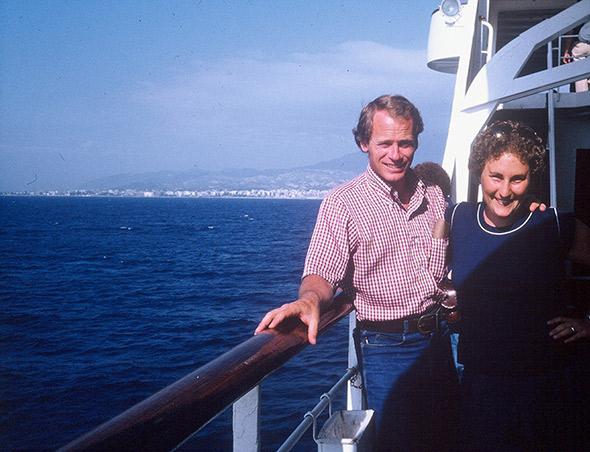

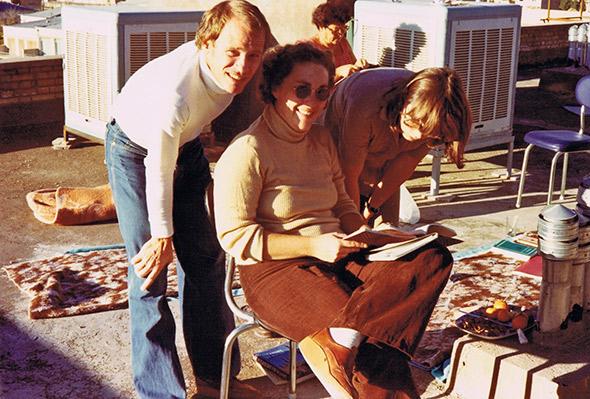

They arrived on June 22, 1978. Lynne was 26, Dave was 32. In pictures they are tan, arms around each other, bellbottoms and newlywed smiles. Lynne looks like Barbra Streisand in A Star Is Born. Dave already has the Johnny Carson comb-over and the Rob Reiner turtlenecks he still wears now.

Their first impression of Shiraz was the dust. The mountains flanking the city were the same beige as the streets. Dust blurred the traffic signs and the smiling posters of the Shah on the street corners, piled up in patterns on the blank walls encircling grand villas and private gardens. Underneath the dust, Shiraz was a hodgepodge of new shops and supermarkets opened during the early-’70s oil boom sharing streets with public buildings abandoned during the bust that followed.

It was, at that time, a great city in which to mingle with other religions. Dave and Lynne rented a duplex owned by a Jewish couple. Every morning they walked past Zoroastrian temples, synagogues, and mosques next door to each other. They bought yogurt and flatbread at shops run by Baha’is, Assyrians, Christians, and Hindus. Dave’s colleagues at the university were Iranian Jews, Indian Christians, British atheists, mixtures of nationalities and religions they had never encountered before.

They rented their apartment unfurnished, so Lynne spent most mornings reading the expat newsletter, the Shiraz Times, for announcements of foreigners moving away. She visited their homes to ask whether they were leaving any furniture behind, and could she have it. With so many foreigners around, she never wondered why so many were leaving.

The center of their social life was St. Simon the Zealot Anglican Church, the only Christian church in Shiraz. It sat within a walled compound, next to expat housing and a huge Christian hospital. The compound had been founded in the early 1940s by Christian missionaries who had set up social services for the poor. Since then the hospital had expanded to offer treatments and surgeries to patients from the neighborhood and the tribal areas and mountain villages just outside Shiraz. It was administered by the Anglican Church of Iran, but few of the doctors and nurses were Christians, and even fewer were missionaries.

Next door, the church was busy. Christians, like everyone else, weren’t allowed to proselytize but were left alone when it came to worshipping. This was fine with Dave and Lynne; that wasn’t the kind of missionaries they were anyway. They started attending the English and Farsi services—every Sunday evening, back to back—to get familiar with the language. Within weeks they were spending most evenings with Iranian or expat friends, taking Friday drives with an Iranian-British couple, Parveen and John, who had met in the United Kingdom and moved to Shiraz to start a family.

Eventually a routine set in. Dave woke up early and biked to the university. He got to know the staff and students, got comfortable enough to tell jokes. “Let me get my two rials in,” he would say when he expressed an opinion. Lynne took Farsi lessons in the morning and taught English at a nursing school in the afternoons. In between, two times a week, she took a public taxicab to pick up their mail from a P.O. box across town, their only connection with the outside world.

The rides to and from the P.O. box were how Lynne met ordinary Iranians, the kind she and Dave wanted to meet. To catch a public taxicab, she stood in an intersection with her arm out. An unmarked car, often already full of passengers, would slow down and Lynne shouted her destination. If the driver was headed that way, he stopped and picked her up. If not, he sped up again. Lynne got good at it, waiting at the intersection, watching some cars speed through, others slowing down, swallowing passengers and spitting them out again.

Eventually Lynne’s Farsi was good enough to make small talk. The other passengers asked her where she was from, what she was doing in Shiraz. Whenever she said she was from America, the response was always the same: “Oh, my brother studies in Los Angeles!” “My cousin is a chef in St. Paul!”

Lynne and Dave knew that there was unrest in Iran, and that the Shah was not as universally liked as the streets named after him and the photos of his wife and family in the newspapers made it seem. Some days Lynne’s visit to the P.O. box took the entire afternoon as the main boulevards filled with anti-Shah demonstrators. She looked at the demonstrators out the window, and all she could see was that they were young and that they were angry. As they passed, Lynne tried to read their bouncing banners, tried to remember what she had read in Time magazine about this man named Ayatollah Khomeini, the stern face on the hand-painted portraits they carried.

No one in Shiraz seemed particularly concerned about the demonstrations. The anti-Western chants never spilled over into Lynne and Dave’s new friendships or taxicab small talk. Jeannie, one of their new expat friends, told Lynne that she had seen kids on her street chanting, “Yankee, go home,” and that afterward one of them had stopped her and asked, in English, “What’s a Yankee?”

Photo courtesy Michael Hobbes

Dave and Lynne attended meetings at the Iran-America Society, where the U.S. State Department answered questions from nervous Americans about the political situation. The answer was always the same: The demonstrations will either fizzle out on their own or the police will crack down on them. The Shah has it under control.

Lynne and Dave’s letters from this period barely mention politics at all. They’re mostly focused on the cultural differences. Dave had never before had to ask a female patient to remove her chador to look at her teeth, and he was not used to having his patients’ male relatives observe their treatments. Lynne had never seen so much male-on-male handholding and cheek kissing. They invited an Iranian couple over for dinner and the first thing they said was “What a nice apartment! … How much is your rent?”

Lynne and Dave both marveled at the cheating. During the first (and only) test he gave his students, Dave was walking between desks.

“Can you move?” asked one of his students. “I can’t see my neighbor’s answers.”

It was the same in Lynne’s job teaching English at the nursing school. Sharing answers was like sharing food; it was rude to keep them all to yourself.

The new social norms also contained hints of things to come, threads of the political and economic grievances that Lynne and Dave, as relatively wealthy foreigners, had the luxury to ignore. Once, when an Iranian colleague complained about all the graduates of the university leaving Iran to practice medicine elsewhere, Dave joked that the Shah should send some police to America to bring all the doctors and dentists back home. Dave’s colleague bolted from his chair and slammed the office door shut. “You can’t talk like that here!” he said. Dave knew about SAVAK, the Shah’s secret police, but he could not feel their presence in the silences between friends and colleagues, not like Iranians could.

There were signs, too, of the tensions left by Iran’s still-sprinting modernization. On a drive to a small village north of Shiraz, Lynne asked Parveen why the road was so nicely paved while most of the others were still gravel. “One of the Shah’s advisers comes from here,” Parveen said. “He doesn’t want to drive home on a rutted road.” In July Lynne was barred from the university pool and told women were no longer welcome. “That’s not actually a rule,” Parveen said, “just a power play by the Muslim students.”

Dave stopped bringing up politics with his Iranian colleagues. If Lynne wanted to write anything about the Shah or the unrest in her letters, she waited until an expat friend was visiting home and asked them to send the letters from London or Amsterdam.

Bit by bit, Lynne and Dave were cut off from the politics of the country where they lived. Letters from home went missing. The media, controlled by the government, was a reliable source of weather forecasts but little else.

Lynne and Dave knew this was happening, that their sources of information were being winnowed down to conversations with expats and English-speaking Iranians. It was troubling, but not a deal breaker. Dave and Lynne were planning to stay in Iran for at least five years. These were just quirks, something you get used to. Whatever country you live in, you expect it to have injustice and corruption, for the politicians to be out of touch, for dissidents to be unhappy. You don’t expect the dissidents to win.

October was the first time their caution turned to fear. In August a packed theater burned down in Abadan and 470 people died. The fire was almost immediately blamed on SAVAK and the Shah, and Lynne and Dave could hear demonstrations in the streets outside their apartment. In Shiite Islam, tragedies are followed by a 40-day grieving period. Forty days after the fire, there was another huge demonstration. Then another 40 days, then another.

Between protests, Dave and Lynne were walking home from a movie when they turned a corner and saw a tank sitting in the intersection like an elephant in a bathtub. The tank was silent, still, more a museum exhibit than a threat, the soldiers surrounding it almost children. They looked terrified, small in their uniforms, holding their AK-47s so tight they might have been shaking. Lynne and Dave looked at the soldiers for a long moment, then turned around and walked back where they came from.

* * *

It was Christmas Day 1978. About 20 people—mostly expats, some missionaries—were gathered in a small apartment in the shadow of the Christian hospital. The hosts, Martin and Helen Gilham, had prepared a full Christmas lunch, complete with mince pies and plum pudding. Carols played on the reel-to-reel.

The party started early. The curfew under martial law was 10 p.m., so everyone had to leave by 9. The guests went back and forth between the apartment and the roof. Up there it was cool, clear; you could see every last wrinkle in the mountains. The roof looked out over the compound wall to the street, but there were no demonstrations that evening, no chants, no smell of tear gas.

Dave and Lynne were glad to be out of the house. In September the university had called and told Dave the school year would be postponed for a week due to the demonstrations. It was delayed another week, then another. By November the university didn’t even call anymore.

Lynne stopped teaching English when the nursing school stopped paying her. She called to tell them that if they didn’t pay, she wouldn’t work. “So don’t work,” the receptionist told her. “No one likes foreigners anyway.” Dave’s salary continued to come, but with inflation at 30 percent, it got smaller every month.

Dave didn’t bike so much anymore. In November a driver had tried to run him into a ditch, yelling, “Death to Americans!” as the car sped away. Lynne still went to the P.O. box, but without the small talk, just the radio playing cassette tapes sent from Khomeini in exile. The scariest thing was the quiet. Fewer cars on the streets, fewer pedestrians. The silence made it seem like the chants, the gunshots, were everywhere.

That couple Dave and Lynne had taken daytrips with? In November Parveen told them that Americans were sucking the blood out of Iran, that an Islamic Republic was the only way for the country to renew itself. John sat in silence, listening, Parveen growing angrier with each breath. That was the last time Dave and Lynne saw them.

Martial law—once you get past the fear, the curfew, the shoot-on-sight orders—is mostly just boring. Dave and Lynne stayed inside, playing Scrabble, reading the Bible, the Shiraz Times, and James Michener, writing letters, stocking up on beans and flour, practicing a flatbread recipe they learned from the Baha’i shopkeepers before their stores were ransacked and shuttered.

They listened to the BBC World Service to find out what was happening in the country where they lived, repeating the scraps of information to each other. It reminded Lynne of being on a military base again, all the social life in daylight living rooms, clumps of people narrating events they couldn’t control.

The community of expats was dwindling. Every week more people left, the congregation of the church smaller every Sunday. Dave’s Jewish colleague left the university in November, telling him, “It’s only a matter of time before they come for the Jews.” The Israeli dean of the dental school dressed up as a Bedouin and escaped by bus to Turkey.

The conversations at parties had once started with “Where are you from?” The question became “Why are you still here?”

Everyone had a story about how things had changed and how quickly. The endless postal strikes, the shops closed because Khomeini’s tapes told them to. Insults, sometimes stones, thrown from cars or balconies. Most of the women wore chadors when they left the house now. Dave and Lynne’s friend Jeannie adopted two Iranian kids, the children of a Baha’i neighbor who disappeared, rather than let them go to an Iranian orphanage.

Martin and Helen had been there the longest, but they had never seen it like this. Helen was a housewife, and their four daughters went to the international school. Earlier that year the family left Iran for six months to return home in England. By the time they came back in September, nothing was the same. The hospitality, the tolerance of difference, the courteous men who helped Helen carry her stroller over the potholes in the street—they were all gone.

Martin and Helen’s flight from London to Tehran had just 12 people on it, almost as many flight attendants as passengers. When they landed the first thing they noticed was the tanks everywhere, then the burning tires, then the soldiers at the intersections. Helen stopped walking into town with the stroller at all.

Helen and her daughters began to stay home during the day. The public schools closed, then opened again, but no one seemed to attend. Helen could hear the students chanting in the streets nearly every day. The demonstration passed each school, shouts of “Death to the Shah” or “Death to America” over and over again. Groups of students came out in a trickle, joined the demonstration, then marched to the next school to gain more recruits.

The demonstrations, as huge and angry as they had become, would still go silent when they walked past the Christian hospital. Many of the demonstrators had been born there. That was where their mothers and sisters had gone to get their flu medicine or their appendixes taken out. The demonstrators filed past, then started chanting again. That was how Helen knew it wasn’t time to leave yet.

For Dave and Lynne, it was the same: The reasons to leave were not yet stacked as high as the reasons to stay. Part of it was ignorance. They did not know the fragility of the place, the tensions the Shah papered over in his rise to power, the bargains he made to keep it.

Photo courtesy Michael Hobbes

In November Lynne attended a meeting at the Iran-America Society where the guy from the State Department said the same thing as always: This was a blip, a detour, nothing to worry about. If it got really bad, he said, the U.S. would evacuate them—for a fee. Besides, wasn’t this why Lynne and Dave moved there in the first place? To demonstrate Christian values through turmoil and peace, in political sickness and in health?

But the real reason they were still in Shiraz was that the scary days were outnumbered by the not-scary days. The shops were still open, the restaurants were full. Lynne gave haircuts to kids from church in her kitchen, caught up on novels, and practiced her Farsi. Dave filled up sketchbooks, visited the university for lunch or tennis with his colleagues, and jumped rope in the backyard on days when the demonstrations kept him from jogging. During the power outages, they stood in the backyard and could see every star in the sky.

Just after dark, everyone sat down for Christmas dinner. They held hands around the table, they bowed their heads and thanked God for his protection. They knew he would tell them when it was time to leave.

* * *

Almost immediately, he did. Every day after Christmas, the knot tightened: Larger protests, harsher crackdowns, popcorn gunshots, bonfires obscuring the night sky.

Dave and Lynne had flights to Jerusalem (via Amman) on Jan. 10—a holiday they had booked months earlier. “If we can hold out until then,” they told each other, “we can just stay in Israel or Jordan until this blows over.”

That is why, when Dave burst through the door that afternoon, nine days after Christmas, and shouted to Lynne that she had an hour to fill a suitcase and leave, her first thought was “Wait, this isn’t supposed to happen until next week.” But with the airport closed, the unrest destroying the normalcy to which they were waiting to return, Lynne and Dave could no longer tell themselves that this was going to blow over.

The company plane took them to Bahrain, and from there they made their way to Israel. In Tel Aviv they read in the newspapers about the destruction of the world they had known. The Iran-America Society, the one where they had attended meetings and asked nervous questions, was burned to the ground, as was the English-language cinema. The reverend at their church was murdered in his office six weeks after they left. Later, the Christian hospital would be taken over by the Revolutionary Guard. Some of their Iranian Christian friends would be arrested and imprisoned.

The only letters they received in Tel Aviv were from Martin and Helen. Martin stayed in Shiraz until after the revolution but stopped leaving the house or seeing patients after the reverend was killed. He finally left in mid-February. He caught a flight through Tehran and spent the night in a hotel where the Revolutionary Guard had rented most of the rooms. He made it out, back to London, where he and Helen still live today. Martin told them he felt lucky: He got to say goodbye before he left.

The compound is still there. Lynne looks at it sometimes on Google Earth. The church still holds worship services every Sunday night, just like always, though no longer back to back with English ones. The hospital is still there too, but it’s not Christian anymore.

Lynne and Dave stayed in Israel for 18 months. Dave got a job at Tel Aviv University and finally got a chance to teach some dentistry. Their first child, my older brother, was born there in December 1979.

The last reminder of their Iran experience came on June 23, 1993, 14 years after that flight. Dave and Lynne had filed a claim in 1982 with the U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, a little-known outpost of the Department of Justice that negotiates settlements with foreign governments after upheavals impact U.S. citizens. After the revolution, the commission filed a sort of class action on behalf of all the Americans who had lost property in Iran. Lynne read about it in the newspaper and sent in documentation of some of the things they had left behind: their plane tickets, bank accounts, the rest of Dave’s contract. Fourteen years later, through the magic of inflation and compound interest, they got a check for $20,000.

Lynne spent the money taking me and my brother—then 11 and 13—to Paris. She brought a copy of Little House on the Prairie in French in her carry-on. Dave stayed home.