For nearly 30 years, my friend Bobby Varga has wondered how anyone could consider the Lebanese Hezbollah movement as anything but a bunch of terrorists.

In September1983, Bobby was flying C-130 hospital aircraft for the U.S. Air Force. When a truck loaded with explosives leveled barracks housing U.S. Marines and French paratroops in Beirut, Lebanon, (killing 241 and 58 respectively), the Air Force dispatched Varga to ferry rows of mangled and maimed soldiers to military hospitals across Europe.

“It was horrible,” he told me. “Sometimes you’d be talking to a guy when the flight began, and then he’d just stop talking, and you’d know, ‘There’s another one gone.’ ”

Since 1983, the United States has regarded the bombing of those barracks—as well as an attack a few months earlier on the U.S. Embassy in Beirut that killed 60 people—as the work of Hezbollah. In fact, since those bombings, the United States has identified Hezbollah as being responsible for dozens of murderous attacks, including the assassination of American University of Beirut President Malcolm Kerr in 1984; the hijacking of a TWA airliner and murder of a U.S. Navy SEAL who was on board; the 1996 bombing of the U.S. Air Force barracks in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, that killed 19; and bombings of Jewish community centers in Buenos Aires, Argentina, that killed 114 people in the early 1990s. That’s why Hezbollah was a charter member of the U.S. State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations when it was launched in 1997.

But somehow when Europe looked at Hezbollah, it didn’t see terrorists, at least not officially. That ended this week when the European Union listed the military wing of Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. Still, it has been nearly 30 years since Hezbollah’s vile attack on U.S. and French service members. How is it that Hezbollah remained off the European Union’s list of banned terrorist groups for so long?

The answer lay partly in the cat-herding process that is EU policymaking; partly in the EU’s desire to remain a mediator between Middle Eastern groups and American and Israeli officials; and partly out of fear for the safety of Austrian, French, Irish, and other EU peacekeepers who patrol United Nations peacekeeping positions between Lebanon and Israel meant to prevent another outbreak of war.

So why the change of heart now?

To be fair, Germany and Britain had long campaigned for listing Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. What may have pushed more of Europe’s doubters into their camp was the airport bombing at the Bulgarian resort city of Burgas a year ago. EU investigators eventually linked Hezbollah to the attack, and it probably helped concentrate minds on the true nature of the group.

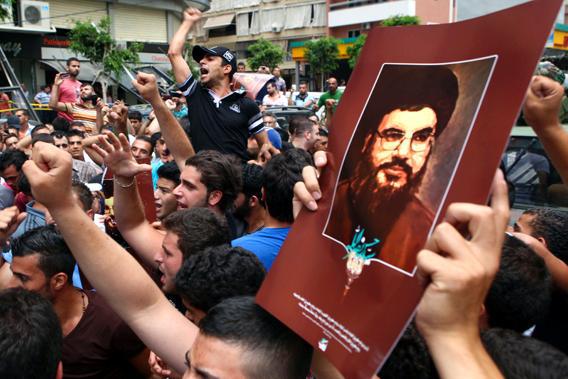

But Hezbollah’s prominent role in propping up Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria has raised the stakes for Europe, too. Indeed, hopes that Europe may be able to act as a mediator in that conflict may explain why the banning of Hezbollah was confined to its “military wing,” a distinction most analysts agree simply does not exist. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah certainly makes no such distinction.

At the end of the day, diplomacy generally prefers a bit of ambiguity, and there is ample history of the United States being slow to state the obvious on such lists. For instance, in 2001, the Taliban was not listed as a foreign terrorist organization or on the separate state sponsors of terrorism list—largely in order to allow U.S. anti-narcotics aid to continue to flow to the poppy-rich nation. This despite harboring Osama Bin Laden, who by that time was tied to bombings of the USS Cole, and U.S. Embassies in East Africa.

The Burgas bombing was significantly less dramatic, of course, and the EU’s decision to ban only the military wing of the Lebanese movement preserves a little wiggle room. But for those like Varga who have seen Hezbollah’s handiwork up close, that’s still more than the group deserves.