BLOEMFONTEIN, South Africa—Billyboy Ramahlele heard the riot before he saw it. It was a February evening in 1996, autumn in South Africa, when cooling breezes from the Cape of Good Hope push north and turn the hot days of the country’s agricultural heartland into sweet nights, when the city of Bloemfontein’s moonlit trees and cornfields rustle sultrily beneath a vast sky glittering with stars. The 32-year-old dormitory manager at the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein was relaxing in front of a wildlife program on the TV with his door open.

Suddenly, he became aware of a new noise. Could it be the trees, rustling in a gust? No, it was heavier, more like trampling. Could it be his TV? He switched it off. The noise grew louder.

Ramahlele got up and poked his head out the door. There he saw the students of the dorm he managed, which housed about 100 black males, some of the first blacks to attend the historically white university since it had integrated four years earlier. And he immediately saw the source of the noise: His boys were stampeding out of the dorm entryway and running toward central campus. Some of them were singing militant songs from an earlier era, when blacks fought against apartheid rule, including one that went Kill the Boer, a nickname for white Afrikaners. Many were holding sticks or cricket bats.

They said they wanted to confront the white boys on campus. The whites, they claimed, refused to treat them as they should be treated in South Africa’s new democracy, and they wanted to put an end to their insolence once and for all. More than one boy opened up his jacket to show Ramahlele a gun tucked inside.

Racing alongside the group, Ramahlele wasn’t truly worried until he rounded the corner and saw, under the starlight, a line of white boys at least as long as his line of black students, standing shoulder-to-shoulder. “It looked like an army flank,” he remembered. The whites were also holding cricket bats, cocked on their shoulders like rifles. Unlike his students, they were eerily silent—until, all as one, they opened their mouths and began to sing. The song was Die Stem, the old apartheid-era national anthem.

Ramahlele’s heart sank. He felt as though he might cry. “The history,” he explained, “is if they’re singing that, somebody is going to die.”

* * *

I first set foot on the University of the Free State (UFS) campus in February of 2010 to study Afrikaans. On paper, the school was integrated: 70 percent of the student body was black. But 15 years after the end of apartheid—the infamous system of racial separation and black oppression that lasted from 1948 until the coming of democracy in 1994—it felt as though apartheid had never ended. The white and black students still seemed to operate in totally different worlds. There were classes in Afrikaans for the whites and classes in English for the blacks, and separate choirs and church services for both. I almost never saw a mixed-race group of students. And they didn’t live together—there were all-white dorms and all-black dorms.

UFS is in the heart of the Free State, the traditional center of Afrikaner power, settled in the mid-19th century by Dutch settlers who trekked inland in covered wagons from the Dutch East India Company’s colony at the Cape of Good Hope 600 miles southwest. They believed they had been sent to Africa by God to become a new people, the Afrikaners (“Africans” in Dutch), to tame the desert—like the Israelites in Canaan—and turn it into a garden. They plowed the region into a fertile grain belt, setting up a republic and naming a capital, pronounced “BLOOM-fun-tayn,” meaning “fountain of blossoms.” The city became a laboratory for the formation of Afrikaner identity. The Afrikaner National Party, the political party that designed apartheid, was established there in 1912. UFS, founded at the same time, was the first South African university to conduct classes in Afrikaans, the Dutch dialect the Afrikaners proudly formalized as part of their new Africa-based ethnicity.

I assumed that old-line attitudes demanding racial separation had never budged in this Afrikaner redoubt. But one day my Afrikaans teacher, Matilda, a warm, arty woman with flowing brown hair, told me there was a much more complicated and disturbing story behind the campus’s racial divide. “Once, this place was the model of integration,” she lamented over coffee at the campus cafe. Leaning forward conspiratorially over her cup, she gave me a clue. “Go to a dorm called Karee,” she said, “and look at a set of photos hanging in the front hall. There, you’ll begin to understand what really happened.”

I went. Karee—named for a drought-resistant tree found in the South African desert—had been built in 1978, as apartheid rule was consolidating and Afrikaans-language universities were expanding. The photos my teacher had mentioned were class photographs. The first dozen or so showed only white boys arranged on the dorm stoop, mugging for the camera. Then, in 1992, a few blacks appeared. There was one looking proud in a mauve suit, and another in a yellow shirt, his hip popped out in a jaunty contrapposto, his lips stretched wide in an enigmatic smile. 1993, 1994, 1995: Every year there were more black students, intermingled with the whites.

And then, in 1997, one year after the riot Billyboy Ramahlele witnessed, something new appeared in the photo: two flags from the age of white supremacy in South Africa—one from the old Afrikaner republic and one from the apartheid state that followed it. They were jarring to see, held high by two white boys in the last row right over the head of a black boy in a wide-brimmed hat. Over the following years, the flags remained, but the black students in the photos disappeared. By 1999, the class photo was all white again, and it stayed that way until 2008, the last year for which there was a picture.

Those images became a consuming mystery for me. UFS hadn’t remained segregated after apartheid’s end—it had integrated and then resegregated later. I wanted to know why the white students raised those ancient flags, and why the black students had left Karee. I uncovered a tale of mutual exhilaration at racial integration giving way to suspicion, anger and even physical violence. It seemed to hold powerful implications well beyond South Africa, about the very nature of social change itself. In our post–civil rights struggle era, we tend to assume progress toward less prejudice and more social tolerance is inevitable—the only variable is speed.

But in Bloemfontein, social progress surged forward. Then it turned back.

* * *

Karee is one of about 20 dorms at UFS that house a few hundred students each. The large brick buildings are situated around the edges of the stately, tree-lined campus, like guardians of tradition, which is what they once were. They had legacy admission. If your mother or father had been in a certain dorm, you’d be in that one, too. In one dorm, freshmen wore striped coats. In another, everybody but the seniors walked in through the back door.

In the early 1990s, South Africa’s universities, all public institutions, were required to integrate as part of the country’s transition to multiracial democracy. Then-UFS President Francois Retief, who was tasked with incorporating black students into an all-white campus, worried about the dorms, he explained in the drawing room of his house in an old-age village on the edge of Bloemfontein. Retief seriously considered housing blacks separately from the whites. “Our dorms were historically more like your fraternities,” he said. “They had a lot of in-house culture. We called them die huise [the houses] and their culture was die tradisies [the traditions].”

These traditions were arbitrary, but they distinguished one dorm from another and fostered a sense of group pride and belonging. Retief feared that his white students might be reluctant to let blacks partake in their long-standing dorm culture. In 1990, he polled the student body to ask their views. To his great surprise, 86 percent welcomed the idea of housing the new black students in the white dorms. So, starting in 1992, he did just that. And it was a “roaring success,” he recounted. The first black students “fit in exactly!”

UFS 1992 Class photo.

Lebohang Mathibela was the boy in the mauve suit in the 1992 class photo on the wall in Karee and one of the first eight black students to live in a UFS dorm. Integration “was beautiful,” he raved when we met at the main campus café. Dressed in a cheerful red T-shirt, Mathibela, now 42, hardly looked older than the 21-year-old in the photo, with cheeks as round as a cherub’s and a pealing laugh. Mathibela has had an accomplished career as a linguist, speaking all 11 official South African languages.

UFS wasn’t a natural choice for a black boy from Johannesburg, his hometown. There were two kinds of historically white colleges in South Africa: those that taught in English and those that taught in Afrikaans. (There were also historically black colleges, but they have generally been of lower academic quality.) The English universities cultivated a liberal, multicultural, anti-apartheid identity; they started admitting black students in the 1980s, when it was still technically illegal to do so. The Afrikaans colleges were reputed to be everything the “English” ones weren’t: conservative, mono-cultural, isolationist. UFS was the most daunting because it was marooned in the grain belt. For most aspirational black college applicants in the 1990s, venturing to UFS would be like choosing Mordor to study.

But UFS was also known for nurturing Afrikaans as a poetic language. That’s what drew Mathibela. In elementary school, he had developed a deep affection for Afrikaans, which was a mandatory school subject under apartheid. It was a mystery to his friends and relatives. “I decided to come to UFS because of my love of Afrikaans,” he said. “My mom was so angry. She said to me, ‘Other children are going to Wits [the University of the Witwatersrand],’ ” Johannesburg’s premier English university. “She says to me, ‘You are not my son anymore!’ ”

After he was placed into Karee, he proceeded to fall in love with UFS’s dorm culture. His favorite ritual was freshman initiation. He laughed as he described it to me, because he recognized that it seemed an unlikely memory to cherish. “We queued blindfolded and half-naked,” he recounted. Seniors painted the freshmen’s bodies in red and yellow stripes to resemble the dorm mascot, a bee. Then they made each initiate drink tomato juice from a toilet bowl. “It looked like vomit! It was horrible! Guys were really getting sick!” Finally, the freshmen were led to a “huge drum filled with water, cow dung and grass.” A senior shouted at them to dyk—dive! “Then you get out. You’re dripping, smelling like cow dung.”

After the cow-dung dip, the black and white freshmen were instructed to go back to their rooms, shower, change into a jacket and tie, and head to the dorm courtyard, where smiling seniors were waiting to hand them a plate of barbecued meat and a beer. “You are a member now,” they informed Mathibela. “Color doesn’t count.”

“I felt proud,” he remembered.

* * *

Like Mathibela, most of the first black students to brave UFS were gung-ho about the dorm culture. UFS had been closed to them, and it was thrilling to be let in and to belong. Another former black student who lived in a mostly white dorm in the early 1990s told me he felt like he was “ascending.”

Their enthusiasm made the white students feel as if they had something worth sharing, bolstering their sense of pride. Mathibela recalls that a white student named Coenraad Jonker pulled him aside. “Where did you learn to speak such beautiful Afrikaans?” he marveled. “You are definitely going to make it here.” White students even bent some of the dorm rules to make it easier on the black students.

And yet, said Mathibela, “I knew it could not last.” As his second and third year ticked by, he was still enjoying himself. But others were starting to grumble. “There were talks that there was going to be a huge change,” he said.

One night, the black students in his dorm gathered in his room. They had been drinking a little, and tongues were loosened. A boy named Shadrack Modise—the boy in yellow in the first integrated 1992 dorm photo, the one with the ironic, perhaps even mocking smile—declared he was having doubts about the dorm’s traditions. Blacks had their own traditions, he pointed out. Most of South Africa’s black tribes have months-long initiation rites administered when a boy is around 16. Blacks are already men by the time they go to university.

He also called attention to the way some of the dorm’s traditions eerily perpetuated old South African power dynamics. Freshmen were forced to wear lackey’s uniforms, address seniors by honorific titles, walk through back doors. These were exactly the things their parents had to do under apartheid. Why should they, free black youth, now do it voluntarily? “This whole thing,” Modise concluded before his rapt audience in Mathibela’s room, “amounts to shit.”

Not privy to the new feelings developing behind closed doors, the administrators thought integration was going astoundingly well. Billyboy Ramahlele recounted his feelings of joy: “Whenever there was a soccer match [in Bloemfontein], I would take a van full of black and white people,” he reminisced, smiling happily. Everybody had expected rural UFS to be a hard nut to crack in terms of integration. But “this university was more advanced than any of its Afrikaans counterparts,” Ramahlele recounted. President Nelson Mandela agreed to accept an honorary doctorate in recognition of UFS’s great strides. “Everybody was talking about us—that we were dealing with these problems so well.”

At the same time, the university reached out to bring in more black students in recognition that the Free State was about 85 percent black. Ramahlele helped lead a radio campaign to recruit black students aggressively. “Every year it [the black cohort at UFS] doubled, doubled, doubled,” he said.

But as more black students arrived, the power balance on campus started to shift. Teuns Verschoor, now one of the university’s vice presidents, was then the administrator in charge of student life. A fatherly mentor type, he is lanky and shaggy-haired and gambols around campus in a brown suede jacket and old-fashioned wool tie, parrying constantly with students. “We started off with 10 percent [black students] in the dorms,” he said. “That was quite something. It was now real contact. But they just fell in with the house cultures. They even decided to start playing rugby—the favorite Afrikaner sport.” When the black student population reached 30 percent, though, “then they started establishing their own identities.”

Everybody I talked to connected with UFS’s history mentioned the number 30 percent. It was a demographic hot line—when the feelings of a few dissidents like Shadrack Modise became the feelings of the whole cohort and black students stopped wanting to go along with the white students’ traditions. They wanted dorm culture to reflect their culture—black culture. They wanted soccer, the black sport, on the common room TV, not rugby.

Choice Makhetha was one of the first black students to join the student council in 1996. There, she fielded a growing number of black complaints. “In one dorm, when you turned 21, you had to run naked,” she remembered. “For black guys, the culture does not allow a 21-year-old guy to run naked with his penis out.”

Teuns Verschoor

Photo courtesy of Sonia Small

Verschoor, whose rumpled approachability made him a natural confidante to white and black students, remembered the complaints: “A lot of black students started asking me questions,” he said. “‘Why do we have to do this tradition or that tradition?’” He held meetings in the dorms to discuss tweaking the practices that were bothering the black students. But as soon as the black students started objecting to the traditions, the white students seemed to close ranks. “Even the white students who actually didn’t like running around naked—it became important to them,” explained Makhetha.

Arnold Bender, a self-described fun-lover, was one of the white students holding up the old South African flag in the 1997 Karee dorm photo with cheeky pride. He recalled that conflict arose over “telephone service,” a tradition wherein freshmen had to man a telephone in the lobby in shifts. As a freshman in 1993, he hadn’t especially enjoyed the duty. But he experienced the black critique of telephone service as an assault on his dignity. “Why should a white freshman do an extra hour of telephone service just because somebody else thinks it’s below him?” he asked me.

He wondered if the black stand against telephone service was about more than just the irritation of answering telephones. “I thought there was some sort of an intent against Afrikaner things,” he said. The restiveness of his black peers made him aware that the tide of things was going against Afrikaners nationally, and made him fear that bigger changes might be in the offing. “I remember one guy told me, ‘It’s discriminatory that the whole university is Afrikaans. They should change it to English.’ ”

The white students had been eager to incorporate the black students into their institutions—on their terms. They hadn’t foreseen that the black students might want the institutions to change to reflect their own preferences. Frederick Retief, the then-president of the university, remembered “having discussions with angry students who said that when they said yes [to integration], they didn’t say yes to this.”

* * *

In many ways, the students at UFS were acting out a greater national drama. When South Africa transitioned to democracy in 1994, the first priority was emotional reconciliation. Over time, though, the theme switched to economic and social transformation. The freed black majority wanted to see material evidence of their bettered status. And yet South Africa’s institutions—business, agriculture and the arts—remained disproportionately white-designed and white-dominated.

Thus, in the second half of the 1990s, the races that had initially come together in South Africa with astonishing joy began to regard each other more warily. Thabo Mbeki, South Africa’s second democratically elected president, proposed a sweeping affirmative action plan and resentfully spoke of “two South Africas,” implying the whites had refused to give up anything of value. Afrikaans town names were changed to blacker ones, and Afrikaans-language schools were shifted to English.

The Afrikaners, for their part, were shocked to learn that the new democracy would result in a seizure of physical and psychological ground. In 1995, F.W. de Klerk, the last apartheid-era president, resigned from the government of unity he’d created with Mandela, alleging the new black leadership refused to treat Afrikaners respectfully. By 1998, a poll showed half of Afrikaners agreed with the statement “South Africa today is a land for blacks; whites will have to accept that they will take second place.” That figure is no surprise—blacks comprise an 85 percent majority of the South African population nationwide, reflecting the demographics of the Free State. The surprise is that when the same poll was done six years earlier, in 1992, a mere 4 percent of Afrikaners had imagined that whites would have to substantively make way after democracy came.

UFS dorms were a microcosm of the new tensions, with young men jockeying for control of physical space. “Black student leaders would return from speaking to me and find people had ejaculated on their blankets,” Verschoor recalled. “And the black guys would form impis”— a Zulu battle line—“and boom, boom, boom, march through the white corridors. It was war.”

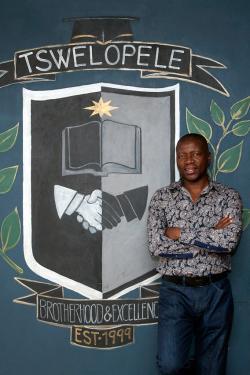

Billyboy Ramahlele

Photo courtesy of Sonia Small

The February 1996 campus battle that Billyboy Ramahele witnessed was a turning point. “Huge numbers of police came,” he remembered. The black students who had run out of his dorm retreated once they glimpsed the line of white boys singing the apartheid-era national anthem. But on their way back to their dorm they “smashed all the cars” of the whites parked on the campus road. Then “they locked themselves in” their dorm. The white boys followed them and began to break the residence’s windows. “There was no windowpane left.” The black boys were afraid to go to bed for fear hostile white contingents would enter through the holes where their bedroom windows had been. “The whole night we slept in the corridors.”

The episode reminded him eerily of the apartheid-era conflict of his youth. Ramahlele grew up in a squalid blacks-only township 35 miles east of Bloemfontein, and multiple times, he had seen gun-swinging white policemen burst into the corrugated-aluminum shack of his mother or his aunts, often while humming snippets of Die Stem.

As he saw it, here on the UFS campus, the white boys seemed to be acting out the military parts their fathers had played in the 1980s, when there was a draft for white men and flanks of white soldiers patrolled the restive black slums putting down protests. The black boys were acting out the roles of the opposition guerilla fighters. The morning after the battle, maids found a stash of Molotov cocktails hidden in the basement of Ramahlele’s dorm—the same kind of bombs Ramahlele used to fashion during his days as an anti-apartheid protester.

The battle convinced the administration that integration could not go on. Ramahlele’s dorm had already, unofficially, gone all black. Its extra rooms had become a refuge for the dissatisfied black students who couldn’t stand to stay in their white-majority dorms. As blacks came to dominate the space, the whites drifted away. Students from other dorms followed suit: Blacks from one dorm came to Makhetha and said, “If we continue to stay together, we will kill each other.” Whites from another dorm visited Verschoor and begged, “Please let us move out.”

So the administrators did. Although segregated dorms never became an official policy, informally the school let students separate. In Karee, the school even let the students put up plywood separating the black and white corridors. The east side of the building became the white side; the west, black.

Verschoor remembers the banal phrase that popped into his head as he watched the plywood go up: “It’s a pity.” But it was also a huge relief. “Suddenly, there was no battle between black and white. And we thought, well, maybe this is the recipe for now.” Like other administrators, he hoped the resegregation would be temporary.

* * *

The fraught race relations at UFS remained a Bloemfontein secret until 2008, when four white boys filmed themselves mock-hazing their black dormitory staff, three cleaning ladies and a male gardener. In the 10-minute clip, they subjected these black elders to a beer-drinking contest, a footrace, and a rugby match. The video culminated with a ritual in which the janitors were made to kneel at the boys’ feet and slurp a muddy-looking concoction out of dog bowls. Just before they drank, the reel cut to one of the white boys pretending to pee into the bowls.

After the video was posted on YouTube by one boy’s spurned girlfriend, angry protests broke out on campus, classes were canceled, and the international news media descended on the university. Foreign reporters took the video to reveal that whites had never accepted blacks outside of South Africa’s cosmopolitan cities of Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban. “Racial apartheid lives on in South Africa’s rural provinces, its small city campuses (like the University of the Free State) and schools, as well as its small towns and farming districts where things have not changed much,” concluded the South African–born, America-based commentator Sean Jacobs in the Guardian.

Even locals came to that conclusion. In the years-long stream of commentaries on UFS in the South African press, the university’s brief period of integration was never mentioned. Most South Africans I speak to express surprise to hear that blacks and whites originally lived together at UFS at all. Eusebius McKaiser, a prominent local talk-radio host, said to me: “That is a very different story than the one we South Africans told ourselves at the time of the video incident.”

It was an easy conclusion to draw. By early 2010, the polarization on campus was absolute; that integration had once flourished there was virtually unimaginable. It was normal to interpret disagreement as functions of innate cultural differences. “I had a fight with a girl who referred to me as ‘you people,’ ” Kefiloe Manthata, a black senior, told me. “I assumed she was referring to black people. Even the most colorblind person,” she explained, “comes here and develops a color way of thinking.”

Braam van Niekerk, a white senior, assured me that profound, inborn differences in psyche and worldview were what kept the races apart. I asked him what these differences were. “Oh, there are so many,” he insisted. “For example, we party on Friday nights. They like to party on Sunday, during the day.”

By this time Billyboy Ramahlele had given up. He could never accept the segregated dorms, and once, sitting in an administration meeting about them, he had a vivid fantasy of the entire campus on fire. “I thought, ‘Let this university go to rubbish! Let it burn!’ And I felt this headache in the back of my head. It wouldn’t go away for a week.” He was diagnosed with hypertension and post-traumatic stress.

* * *

When I described the integration and resegregation at UFS to Edwin Smith, a leading black education theorist and administrator at the University of Pretoria, the main university in South Africa’s capital, he wasn’t surprised. All South African universities, he said, have struggled with race relations in their dorms, even the English ones with a liberal reputation. I asked him which of South Africa’s 15-odd major universities were thoroughly integrated nearly 20 years after apartheid’s end. “There aren’t any!” he answered, chuckling with resignation.

The phenomenon is not unique to South Africa, either. In certain ways, it mirrors dynamics that occurred on American campuses as they began to integrate during the 1960s and 1970s. john a. powell, a nationally renowned civil rights lawyer and education expert who prefers to present his name in the lower case, recalled entering Stanford in 1965 as one of 28 black students in a thousand-strong freshman class. Like the white students who welcomed Lebohang Mathibela in their dormitory, most of the whites at Stanford were “friendly,” powell said. “But they expected us to do things”—like rushing fraternities—“on their terms.” The expectation was that the blacks would assimilate to white norms, not that the institution itself would have to change to accommodate them. Stanford even hired a psychologist to help the black students assimilate, inviting them to meet her at a lawn party featuring the Jim Crow-era stereotype of black people’s favorite food, watermelon.

In race theory, “we speak of a ‘tipping point,’” powell explained, “a point at which a minority reaches a critical mass and the racial dynamics suddenly change.” The minority starts chafing against institutional traditions, and the majority experiences anxiety that almost every familiar feature of their lives could become imperiled. In America, though, few historically white universities have reached a 30 percent tipping point—yet. In this way, transformation at UFS is not behind but ahead of American transformation, not an echo but an augury for our country, where last year nonwhite births outpaced white births for the first time.

The UFS story suggests how dangerous it is to let polarization take hold. Like many institutions facing a demographic shift, UFS initially failed to take an active enough role in managing the change. “Typically, management doesn’t track what’s happening, because they think change will happen organically,” reflected powell. “They may also be afraid to confront the implications of change.” At UFS, given the demographics of the Free State, the implications were that eventually, somewhere down the line, the character of the university would change enormously. An administration composed mostly of older white Afrikaners, well-disposed toward modest change as they were, didn’t adequately face that stark reality. They failed to encourage the formation of a new, joint identity and allowed prejudices to deepen—making it exponentially harder to bring the two sides together again.

* * *

But not impossible. In 2009, a charismatic Stanford Ph.D., who quotes Shrek and Edward Said in the same breath, arrived at UFS to undermine the status quo. Brought onto troubled campus after troubled campus to heal them, Jonathan Jansen is South Africa’s most prominent university leader. He’s also the first black president UFS had ever appointed. Four years into his tenure, he has made dramatic inroads toward reintegrating many of the dorms, winning praise from black and white students alike.

Photo courtesy of Sonia Small

On a December afternoon, underneath a steely gray sky brewing a thunderstorm, I took a walk with Jansen across the UFS campus. At first, “I was scared to death,” he admitted, while overlooking the campus’s main quad. The first time he walked on campus, “you’d stand here and you’d see a patch of black kids, a patch of white kids. That exists at all South African universities, but it was so absolute here.” He despaired anything could be done. “It’s the way the country was wired.”

But he decided if the students had no practice making bridges between black and white, he would lead by being the bridge himself. He began with a Nelson Mandela–like gesture: In his inauguration speech, he announced the university would forgive the four Afrikaner students who filmed the video humiliating their janitors and accept its own institutional responsibility for the event. “They are my students,” he declared in the speech. “I cannot deny them any more than I can deny my own children.” He followed up by deepening his engagement with the community, penning a regular column in the local Afrikaans paper and becoming a constant, nearly ubiquitous presence in student spaces. Sometimes he drags his desk outside the administration building and sets it up under a tree to encourage students to hang out.

“I use Twitter,” he said. “Facebook. I just walk and talk.” As well as being approachable, Jansen has also been somewhat autocratic. He has shown that pairing these two traits can be extraordinarily effective in a chaotic milieu like UFS. Jansen always made his end goal perfectly clear: full reintegration of the dorms, even though three-quarters of Afrikaner students had openly admitted in a 2007 campus poll that they preferred segregated living. In his first year, he demanded that every dorm integrate its freshman class 50–50, no migrations allowed, and unilaterally banned most of the dorm customs that had been lightning rods. He also instituted mandatory dorm conversations on race. “It’s extremely important to make the vision explicit,” he explained. “All we do is talk every single day in every single meeting about … the human project” of integration.

Sitting down with me in a dorm called Khyalami, which means “our home” in Zulu, a handful of current students and recent graduates spoke about the change Jansen had wrought. Phiwe Mathe, a soft-spoken political science major in a blue polo shirt and neatly pressed jeans, said he had at first been “outraged” by Jansen’s decision to forgive the four video-makers. “But now I praise him for taking that action,” he said. “He came into an environment full of tension, and he became the neutral figure.”

Emme-Lancia Faro, a sportily dressed woman of mixed racial heritage who was recently elected head of a formerly all-white girls’ dorm, pointed to the emotionally charged meetings that Jansen demanded. In them, students are encouraged to let fly with all the prejudices they have about the other race group. Initially she felt “shocked” to hear some whites suggest blacks were lazy or didn’t like to shower. But then she realized that she too harbored negative stereotypes about whites she had never consciously articulated—like that all of them are rich. At Jansen’s so-called cultural renewal evenings, “I was changed,” Faro recalled.

The students acknowledge there remains one nut left to crack: white men. Today, the UFS women’s dorms are demographically integrated, and male dorms that had been all white during the segregated decade are getting there, too. But male dorms that went “black” during the resegregation of the 1990s are still mostly black. When white boys hear that they’ve been placed in a historically black dorm, they usually choose to move off campus instead. The two dorms with black-sounding names—Khyalami and Tswelopele, which means “progress”—are having an especially hard time attracting white men.

Abel Jordaan is one of nine white men living in the 179-bed Khyalami. He loves it, and he laments the difficulty of retaining other whites. “They look at the name,” he said. “For Afrikaner students coming here, because of the history, we’re still struggling with stereotypes.”

One of the places white male students have fled to be out of Jansen’s reach is a private dormitory named Heimat, a German word for homeland that is a common name of dorms at Afrikaans universities. In it, the old UFS dorm traditions are front and center. In its first year, 2009, the year Jansen showed up to campus, Heimat welcomed 40 UFS boys, then 70, then 100.

Over the course of an afternoon, I met some 30 Heimat residents. One or two didn’t hesitate to state that a sense of white superiority had led them to choose Heimat, but most suggested they’d chosen the dorm not from a surfeit of confidence but out of fear—fear over what permanent place the white man will have in black-ruled South Africa. Over the past few years, the country’s most prominent black youth politician, Julius Malema, has suggested that President Jacob Zuma’s government should stop developing white residential areas and expropriate white-owned mines, and the government itself has declared its intent to transfer 30 percent of white-owned farms—the birthplaces of many of the Heimat boys—to blacks by 2025. Afrikaans-language educational spaces have already dwindled tremendously, with more than 90 percent of formerly Afrikaans schools closed or made bilingual since 1990. “I’m in love with my country, but does she still love me?” goes the anxious refrain of a popular Afrikaans country-and-western song played often on the radio. Many of the students mentioned the example of Zimbabwe next door, where Robert Mugabe’s government first preached racial reconciliation but later expropriated white farms and violently expelled those who resisted.

Amid this pervasive sense of vulnerability, Heimat feels like a safe space. Hewing religiously to the dorm traditions, however random they might seem to be, allows the Heimat boys to feel they still have a legitimate culture—a culture that might protect them in a time of need.

A freshman named Piet Le Roux took me to his bedroom to show me the exacting way the dorm manager makes freshmen arrange their clothes and toiletries for morning inspection. Shirts stacked from light to dark. Toothbrush, toothpaste, shaver, shaving cream and Bible, lined up in that order on the bed. Mix it up and you have to do push-ups.

Did such customs ever feel arbitrary? I asked. Le Roux shook his head no. “It makes you big for the future.”

It’s not only young white men who are resisting Jansen’s vision. Black critics, especially those outside the university community, point to the overwhelmingly black demographics of the Free State and the nation’s persistent dearth of opportunities for blacks. They question why a fragile racial reconciliation should be permanently sustained by fastidiously maintaining integration between whites and blacks. Edwin Smith, the black education theorist, told me he respects Jansen enormously, but “this is an African country,” he pointed out. “Until our institutions are dominated by black people, you are still going to have a lopsided culture” that favors whites.

To those living on campus, though, the university has become a comforting manifestation in miniature of the dreamed-for post-racial South Africa. Billyboy Ramahlele, now in charge of a university outreach program to primary and secondary schools, remains worried about South Africa’s future. But haunted as he still is by the riot and the collapse of integration in the 1990s, the changes Jansen has wrought have given him hope once more. “The atmosphere has changed,” he said, his voice brightening. “We are moving toward students realizing the realities of society, of interacting with each other. Students are learning about other belief systems. So many things have changed.”

This article originally appeared in Moment Magazine’s May/June issue. Moment Magazine is an independent bimonthly of politics, culture, and religion, co-founded by Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel. For more go to momentmag.com