I was in London when things got serious in Turkey. I tried my best to spread word about the protests by sharing videos and photos on Twitter and Facebook, and I stayed up every night, reading everything I could about what was happening in the streets. Local Turkish media wasn’t covering the protests at all. (They aired cooking shows and documentaries about penguins instead.) Only those in the street or with access to social media knew what was going on. Sleep wasn’t an option. I managed to return to Istanbul on Sunday night. On the flight back home, I was excited and nervous, the way you feel before a first date.

On Monday morning, I showed up at the office. For my co-workers and me, daily life is not interrupted. It is hard to concentrate on anything besides the protests, but we have maintained our daytime routines. We are workers by day and resisters by night.

I left my office in the Etiler neighborhood at 7 p.m. and headed toward Taksim Gezi Park. The roads were already flooding with people. It’s about a 4-mile hike. Residents of Istanbul walk everywhere now. They will travel unbelievable distances by foot, crossing continents holding hands. The notion of distance has ceased to exist.

My backpack had bottles of water, milk, extra sweaters, goggles, a box of masks—gas masks are very fashionable these days—and Rennie, a brand of tablets that wards off heartburn. (We have found that if you mix the Rennie with water or milk, the solution helps relieve the burning sensation on your eyes and skin caused by tear gas.) One of my friends stopped at a pharmacy along the way to pick up some Rennie. The pharmacist, after confirming that my friend was heading to the protests, refused to take any money. He told him his store doesn’t charge protesters.

When we finally got to Taksim Square, walking down these famous streets now spray-painted with humorous and peaceful slogans, I received a text message that told me to warn a group walking from Etiler that there was a police ambush on the way to Beşiktaş and to not let the warning go out on social media. I forwarded the message to everyone I could think of.

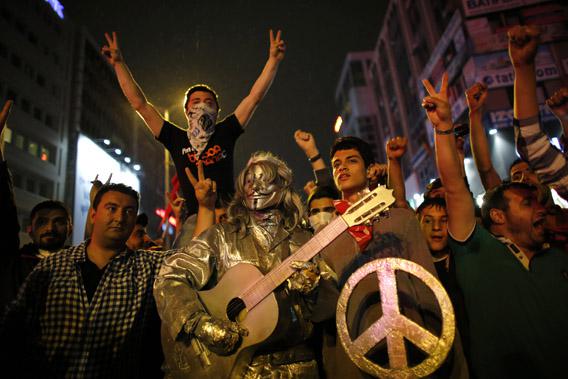

Taksim Square felt oddly safe, with all the music, drums, dancing, laughs, cheers, slogans, the fresh smell of spray paint, and vendors selling watermelon and meatballs. The clumsy, makeshift barricades that protesters had placed on the streets leading up to the square were a reminder of the danger. The facade of a Burger King had been spray-painted in red: FIRST AID–INFIRMARY. A couple of days earlier, protesters had taken refuge there and wanted to let others know that they could get medical assistance.

*

The mood was festive, but everybody was prepared for an attack. And then the first tear-gas bomb was lobbed down at the crowd at 9 p.m. By then, we knew that there were police in Gümüşsuyu—the neighborhood that connects Beşiktaş and Taksim Square—but there were no officers in sight. When the first tear-gas bomb hit the park, we didn’t see any smoke, nor did we hear the sound of a tear-gas canister exploding. People remained calm, which was astonishing and heart breaking at the same time. People were just looking after each other, asking everyone around them if they were OK and offering to spray some Rennie solution or vinegar on their face to combat the tear gas. A helicopter appeared overhead every once in a while, and every time it did we felt the smoke again. It was a different kind of gas this time, everybody said. Turks, after all, have become experts on tear gas by now.

*

I was a volunteer at the pop-up kitchen in the park. My shift started at 12:30 a.m. We were responsible for organizing and setting out the bags of food and beverages that was constantly being delivered by the public. We were also responsible for making sure people drank milk and not water after being exposed to gas, because milk soothes the burning and water does no good. Every single person said, “Thank you.” No one took more than what he or she needed. No one refused to help, no questions asked. We worked around the clock. Three hours felt like 15 minutes. I didn’t want to leave, nobody wanted to leave, but we all knew we must sleep, even if we don’t remember how.

We found love in the violence. One needs to experience this kind of love to understand it. It’s hard to get used to, but it is easy to get addicted. It makes you want to hug everyone on the street or propose to your loved one. It makes the public come together: the protestors living in Gezi Park, the mothers at home telling their children how proud they are, the ones living abroad that are trying to get the world to pay attention, the resistors that get beaten up, the pharmacy that won’t accept any money, and so many more. The Turkish public is united in its fight for freedom, and we know how to have fun doing so.